I enjoyed reading Dr. Michael Banner’s article, “Riding The Storm Out,” in January’s issue. It was highly enlightening and well-written. I will now adopt the VB speed after reading the article.

288

However, I would like to ask what pilots should do in those cases when turbulence is unanticipated. For example, what is a pilot to do when all of a sudden he/she enters an area of clear air turbulence or sudden severe disturbances in the surrounding air mass? I understand that convention has it that clear air turbulence occurs most commonly at higher altitudes. Nevertheless, are there some pearls of wisdom for us if we are travelling at cruise speeds and suddenly encounter increased G forces?

Also, after flying through turbulence, how do we know if we have possibly endangered the plane’s physical structure (for future flights), but not quite to the point of “breaking it”?

Thank you for your work on the magazine and to Dr. Banner for his article.

Bob M.

via e-mail

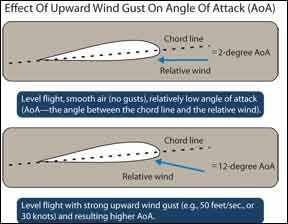

When we encounter unexpected turbulence, we immediately reduce power and slow to an appropriate speed, based on the airplane’s operating weight. That said, turbulence can be anticipated in many ways: on the lee side of mountains or tall objects, associated with strong winds and unusual cloud formations, as identified by nearby aircraft on the frequency or via Pireps.

Installing a G-meter, admittedly rare in non-aerobatic airplanes, is one way to determine if the structure is overstressed, but a detailed inspection is the only certain method of discovering airframe damage.

Power To The Tablet

The sidebar “Tapping Ship’s Power” accompanying February’s article on portable electronics, “Gadget Flight Rules,” includes several comments concerning an iPad’s power draw.

I’m not sure what you are using as a point of reference, but the iPad consumes less than 15 watts of power through its charging port, which is less than one ampere at 14 volts and less than ½ ampere at 28 volts. Not what I would call demanding or a high power draw.

288

It’s more than a cellphone, sure, but it’s far less than a single (non-LED) nav light, which consumes approximately 25 watts of power, or two amperes at 14 volts.

Dan Garley

Via e-mail

You’re right, of course. What we were trying to get across, and at which we failed miserably, is that popular tablet computers have greater charging demands than their smartphone cousins. This is true for Apple iOS devices as well as Android-based portables.

What we should have said is pilots can’t expect a charging adapter designed for an Android or iOS cellphone to output enough power to charge a tablet using the same operating system, especially while it’s being used in the cockpit. We discovered this the hard way, on both an iPad and a Nexus 7.

When using a tablet in the cockpit, a cigar-lighter adapter capable of supplying enough power to operate the device and charge it should be used. Often, a smartphone charging adapter won’t be enough. Thanks for allowing us to clarify this point.

Landing With A Flat Tire

I have a question about November’s article, “The Bold Print.” If you didn’t notice a flat tire in pre-flight, how would you know you had one, since it wouldn’t appear flat without weight on it, assuming you could see it while airborne in the first place?

Lindsay Petre

Via e-mail

Good question. We used that graphic to prove a point about “bold-print” checklist items. In this case, Cessna provides the procedure but doesn’t tell us how to discover the flat tire.

The only way we know would be to compare a suspect main tire with the other one, presuming a high-wing airplane lacking wheel pants. Those of us flying low-wing airplanes will discover the problem on touchdown. If we catch it, we’ll go around, then execute the procedure.