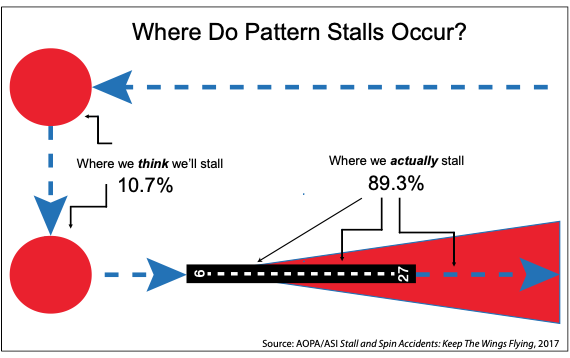

In 2006, I was living and working in the Melbourne, Fla., area. On March 23, there was a crash at the Melbourne Orlando International Airport: A Cessna 340A was on final and was asked to slow, and it did. Too much. The result was a stall/crash as described in Tom Turner’s article, “Stalls In The Pattern” (August 2022). After a few days waiting for the formal, onsite investigation to finish, I went to the crash location to take a look for myself.

The aircraft came down near the edge of a grove of trees that all appeared to be 25-to-30 feet tall, and I was absolutely amazed at how vertical the aircraft’s descent appeared to be. I saw zero indication of any forward (toward the runway) velocity. That really impressed on me that airspeed was critical while in the pattern.

Tom Cash – Via email

Thanks, Tom!

FLUTTER LIMITATIONS

Mike Berry’s piece in your June 2022 issue, “Living With Limitations,” is a great article, but what about flutter-speed limitations at altitude?

Cruising at 132 KIAS at 17,000 feet in my Mooney, is it safe to leave the power at cruise and push over to the yellow arc, turbulence permitting?

I have never found any such guidance, and the problem with flutter is when you find it, it’s too late.

Scott Burkhart – Via email

No, it’s probably not safe to do that. We explored some of this in a January 2011 article by Steven Gibb, “Slow Down, You Move Too Fast,” which highlighted that VNE is a true airspeed. That article included the following:

“Of course, true airspeed and indicated airspeed are going to be the same value only at sea-level density altitude with standard atmospheric conditions. At much higher density altitudes, flying at an indicated airspeed, even in the green arc below VNO, can result in a true airspeed substantially exceeding the VNE redline.”

A second passage in that article reads, “In a Mooney 231, the top of the green arc (VNO) is 174 knots. At any altitude above density altitude of 8000 feet, a calibrated airspeed of 174 knots would yield a true airspeed greater than the 196-knot VNE.”

WHOSE RESPONSIBILITY IS IT?

While reading the June 2022 editorial, “Is It Safe,” I noticed an anomaly. On page 2, you state, “An aircraft’s mechanical condition is the pilot’s responsibility, also, but we often don’t have all the information necessary to make informed judgments.”

On the final page, you state: “But according to the airplane’s maintenance logs, it hadn’t been accomplished in the almost 13 years preceding the accident. From the record, it’s not clear that the owner/operator or the mechanic knew of the recommendation, or even that there was a suction screen that should be cleaned.”

From what I read, the owner/operator (could be a rental facility) is not responsible for the mechanical condition and that the pilot (could be a renter with low time, like me) is responsible? How is the pilot responsible for the mechanical condition, especially as a renter when the maintenance logs are not in the airplane? Was the page 2 reference to “pilot’s” a mistake? Can you please clarify?

Keep up the great work. I fly vicariously through this magazine and love keeping all its knowledge in the mental bank, hoping I will never have to use most of it. But if the poop hits the rotating oscillator, I feel pretty confident.

Greg Lary – Via email

This arises from FAR 91.7, which states, “(a) No person may operate a civil aircraft unless it is in an airworthy condition” and “(b) The pilot in command of a civil aircraft is responsible for determining whether that aircraft is in condition for safe flight….”

“Airworthy” is doing a lot of work here, in that airworthiness often is determined by the aircraft’s paperwork instead of its true mechanical condition. That said, most renters and owners alike often take it on faith that the paperwork is complete and the aircraft is mechanically sound.