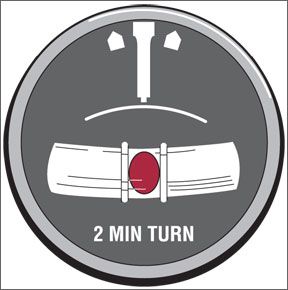

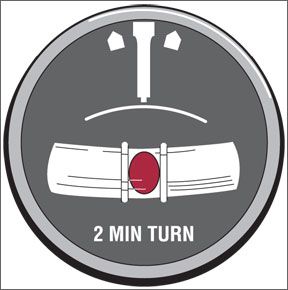

First of all, “Playing Mental Defense” (March 2010) was an excellent article. I would like to offer clarification on a key technical point, however. Mr. Pestal correctly identifies “cognitive dissonance” as the condition of psychological discomfort experienced when competing cognitions occur. He also correctly described the human tendency to attempt to 288 resolve the cognitive dissonance by utilizing denial, rationalization and other unproductive defense mechanisms as we seek to return to a state of psychological comfort. We in psychology refer to this process as “dissonance reduction” or “dissonance resolution.” The picture became muddied when Mr. Pestal equated the state of cognitive dissonance with the process of dissonance resolution and advocated combating cognitive dissonance. It would be more precise, and more useful, to advocate utilizing the experience of cognitive dissonance as a type of mental annunciator light-a warning that something is amiss and that one is now vulnerable to making a poor decision due to ones natural inclination toward seeking dissonance resolution in order to return to a state of psychological comfort. It is the type of dissonance resolution engaged that is the critical factor. Rather than engaging in unproductive/unsafe dissonance resolution (e.g., denial, rationalization, etc.), the aeronautically safe solution-as Mr. Pestal correctly noted-is to recognize the vulnerability indicated by the dissonance and to consciously choose a safe alternative. Hence, in contrast to what the article indicated, cognitive dissonance is the pilots ally (his or her internal annunciator/warning light). It is faulty dissonance resolution that is the pilots enemy. Good situational awareness, to include awareness of ones own cognitive state and vulnerabilities, includes recognizing cognitive dissonance and utilizing the information it provides as a prompt for purposeful and rational aeronautical decision-making in order to enhance flight safety. I love your magazine. Reading it is making me a better pilot. I just renewed my subscription for another two years. Thanks for your great work. Chris M. Front, Psy.D. Thanks, Chris. Always good to know 800 Independence is paying attention. Thanks also for your kind words, and for the clarifications regarding cognitive dissonance and how we respond to it. Slip-Sliding Away Great article on the turn coordinator, which sometimes seems to be a neglected corner of the instrument panel these days. About halfway through the article, though, I began to experience a little of the cognitive dissonance mentioned earlier in the same issue. Wait, I thought a skid was when there was too much yaw for the bank angle. But the article says, “If youre looking at the T&B instrument at top, youre in a skid; yaw/heading change is too little for the established bank.” Feeling a headache coming on, I finally had to pull out my copy of the FAAs Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge to verify I actually was remembering correctly. I hate to nitpick, but the slip/skid concept is confusing enough for most people that you probably ought to issue a clarification. Thanks for a great publication. Lisa Pierson Somehow, we knew this was going to happen. That the bunch of rated pilots who looked at that article before it went to press can screw up only highlights how confusing this topic can be. The artwork and accompanying text on page 14 of our March issue depicting a turn and bank instrument in a skid and in a slip is correct. However, the sentence you cite should have read, “If youre looking at the T&B instrument at top, youre in a skid; yaw/heading change is too great for the established bank.” Thanks for the catch! RADARs Shortcomings Without trying to be pedantic, there are many other weather phenomena with the potential of damaging aircraft but which are not detectable by airborne radar (“Reading Radar Right,” March 2010). In the days before color weather radar, an instructor made the 288 point to me that, in any convective weather, pilots should consider the possibility of there being turbulence in even the lightest green (monochrome radar) or green (color radar) as severe as any in the heavier areas being painted. Never, ever fly into a shadow where ground clutter cannot be painted behind or beyond a radar return. I read each issue of Aviation Safety as soon as possible after receiving it. Thank you. Charles Nicholson Wake Turbulence Spacing A group of my pilot friends and I were doing some hangar flying recently and ended up in a rather testy conversation regarding wake turbulence separation requirements and our different experiences with controllers at different airports, especially when considering intersection departures. Maybe you can help set us straight? The basic question is when does the three-minute clock start, and from what point does ATC start measuring the required 500 feet? We all agree tower controllers do not routinely monitor an aircraft from the start of a takeoff roll to wheels-up. But how can there be absolutes when one starts with variables? Any light you could shed on this? John P. Hanlon Well give it a shot, even as we make a note to gin up a future article on the overall topic of wake turbulence. The first place to start trying to understand anything associated with air traffic control is FAA Order JO 7110.65T, Air Traffic Control, the FAAs “bible” when it comes to ATC procedures and phraseology. Its available at the agencys Web site-tinyurl.com/atcorder-in PDF format. Paragraph 3-9-7 addresses wake turbulence separation for intersection departures. It specifically states the three-minute rule applies from the moment at which the heavier aircraft takes off: The following aircraft should not begin its takeoff roll until the three minutes have elapsed. Note that a three-minute delay is mandatory when the preceding aircraft is a Boeing 757 or classified as “heavy.” Meanwhile, the only two instances involving wake turbulence we found where distance matters is a) if the following aircraft is operated by the U.S. Army and the intersection is 500 feet or less from the departure point of the preceding aircraft and, b) if parallel runways more than 2500 feet apart and offset by more than 500 feet and an intersection departure is being performed. Jet blast is an entirely different topic. Were not aware of specific FAA guidance on how far a small aircraft should remain behind a large jet, but 500 feet sounds pretty good. We note large jets at low power settings can generate near-100-knot winds more than 200 feet behind them.

Office of Aerospace Medicine

Federal Aviation Administration

Wilson, Wyo.

FAAST Representative

Greensboro, N.C.

Concordville, Pa.