If you have been following aviation news for the last, say, 20 years, you have probably read a thing or two about smoke and fume events. What is so insidious about these events is that their prominent manifestation is a “dirty sock” odor, followed by dizziness, disorientation and an array of other symptoms. Before specific training was widely incorporated, by the time the flight crews realized something wrong, the damage was done. Crews reported not remembering landings and a few pilots with acute exposure died.

The most common reason for these fume events is a lubricant ending up in the aircraft’s cabin pressurization system, distributing toxic fumes throughout the pressure vessel. While this specific failure is an unlikely occurrence in most general aviation aircraft, there are still lessons to be learned from dealing with situations like these. A common factor in these events is that, while the crew attempts to investigate the source of the smoke or fumes, the situation devolves. The smoke may turn into a full-fledged fire, or the fumes may be actively poisoning the aircraft’s occupants. Preventing the event is obviously the first choice, but once that barrier has been breached, crews need to recognize the warning signs and respond according to their training.

Recognition, Investigation

According to the folks at Griffith University’s Strategic Study Centre and their Study on The Effects of Startle on Pilots During Critical Events, which we also discussed in December’s article, Fear Factors, “The ubiquitous reliability of modern aircraft has created an unconscious expectation of normalcy amongst Pilots. This lack of expectation for things going wrong can have negative effects on acute stress levels and startle reactions.”

Generally, smoke events are pretty cut and dry. If you see smoke, that generally breaks the façade of normalcy. Fumes can be subtle, especially at first. My recommendation is if you smell an unfamiliar odor, and there are other occupants on board, wait and see if they mention it. If you bring it up, two things happen. One, the other pilots or passengers will immediately start deeply inhaling potentially toxic air, trying to detect a fume. Two, aircraft often have an aroma of generally unfamiliar smells to non-frequent fliers. If prompted, most people will find some odd smell they aren’t used to. On the other hand, if they suddenly announce, “What is that smell?!” you will have no doubt something is awry.

Now there are some caveats to this, most notably that if two people have this mindset, they may both sit in silence smelling an acrid smell, waiting for the other to confirm their suspicion. This recommendation comes with a time limit of a minute or two until querying others and beginning to troubleshoot.

Additionally, it does not help if you are alone. Depending on workload, if you suspect a fume event, start troubleshooting immediately. Worst-case scenario is you get some valuable experience simulating a fume event. The best case is you eliminate the problem before it grows.

Common Causes

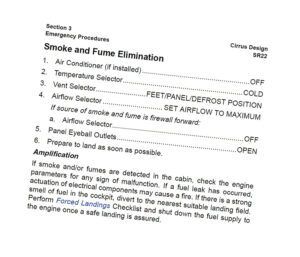

The Cirrus SR-22’s airplane flight manual (AFM) smoke and fumes checklist has an “If/Then” style that includes, “If source of smoke and fume is firewall forward,” which is a great way to think about fire sources and causes. The aircraft’s engine, oil and fuel system literally work together to manage oxygen, heat and fuel, the three main ingredients of a fire. When components fail or some part of the system is not working correctly, the ingredients for smoke and fumes are right there.

In that checklist, the first step of the source of smoke/fume is firewall forward is to close the airflow selector. This is always good advice. If cabin heat or any air-conditioning system uses any component of the engine, it should be shut off/closed/isolated first thing. (Hint: Typical single-engine piston airplanes pass fresh air over the exhaust system to heat it before directing it to the cabin.) Check engine parameters for abnormalities and prepare to run the engine fire checklist. If the fume odor is fuel, exercise extreme caution actuating electrical components, as this could spark a fire.

The particularly deadly fume event is carbon monoxide (CO) from a leaking exhaust system, in part because it is invisible and odorless. In the sidebar about emergency equipment, on the opposite page, I mention valuable (but cheap!) CO detectors that I would not fly without, but in addition, it is wise to brush up on the symptoms of carbon monoxide poisoning because early detection is critical.

There are a number of factory or aftermarket air conditioners available for general aviation aircraft. I tried my hardest to find more information on occurrences similar to this with no luck. The story stuck with me, and I trust the pilot who this happened too, so I feel comfortable circulating the rumor. One of these AC units was installed under the pilot’s seat. Something failed within the unit and started smoking in flight. Luckily, once the unit was shut off and isolated, everything cooled off, but can you imagine a worse place for a fire to start?

Additionally, any pressurized aircraft can have issues with conditioned air entering the cabin. The system is meant to reduce the pressure and temperature of engine bleed air, but components can fail and foreign substances (like the smoke from burning oil) can enter the cabin. Follow any smoke and fume removal checklists that your aircraft’s manufacturer publishes, but I would bet turning these systems off will be high up on the list.

Having the proper equipment handy and accessible is vital in a smoke or fume situation. Here are some examples of life-saving equipment.

Having the proper equipment handy and accessible is vital in a smoke or fume situation. Here are some examples of life-saving equipment.

- Fire Extinguisher: It is surprising to me that under FAR 91, light GA aircraft are not required to carry a fire extinguisher. They are one of the least expensive and easiest ways to improve safety while operating an aircraft.

- Carbon Monoxide Detector: Another relatively inexpensive and easy-to-use device is a battery-powered electronic CO detector. Ideally, you want one that alerts at low ppm values. Some avionics manufacturers are incorporating detectors into their products.

- Oxygen: If your plane has installed oxygen masks, test them to manufacturer’s standards and practice donning them occasionally. Masks stowed for years can fail right when you need them. Even a single breath of fresh air could make all the difference. But ensure oxygen components do not come near the fire/smoke source.

Cabin Fire

If you have never seen a lithium-ion battery fire, do yourself a favor and find a video through your favorite search engine. It does not have to be a huge battery; a laptop or even a cellphone can really do some damage. In the airline world, it is not unheard of to find small fires in lavatory trash cans from poorly extinguished cigarettes. While most of the general aviation planes I have flown still have ashtrays, I would strongly recommend not smoking for all occupants for so many reasons, including the fire hazard.

The long and short of cabin fires is knowing what is on your aircraft and where. It is the pilot-in-command’s responsibility to ensure that there is nothing flammable or any other hazardous material on board, but this is often easier said than done.

Generally, a cabin fire is preceded by an acrid, burning odor or smoke. Time is critical, and it is much easier to prevent a fire from starting than to fight it once it’s engaged. Again, especially if you are flying single-pilot, this can be challenging or impossible. Consider loading items such as laptops or anything else that could create flames within reach of yourself and a fire extinguisher, because fighting a fire in an inaccessible cargo area may not be possible.

Electrical

Anything using electricity is a fire threat. Most of us are familiar with the “burning electrical” smell, and it is not something that elicits a comfortable feeling when operating an aircraft. Circuit breakers popping and malfunctioning electrical equipment are other symptoms of a dangerously overheating electrical system. I would be remiss if I did not mention using extreme caution when resetting CBs in flight. Personally, I will not do it, unless I absolutely need the affected system to safely find a suitable landing spot.

Known, Unknown Sources

A known source of smoke and fumes is not ideal, but at least there are actionable steps to be taken. If the source is unknown, a well-written checklist should help navigate the “trial and error” troubleshooting method of turning off systems to see if anything improves. Out of curiosity, I reviewed a few checklists. In the PC-12, “proceed to nearest airfield” is step eight on the smoke and fume checklist. In the Cirrus SR-22, “prepare to land as soon as possible” is step seven.

What’s Next?

As a rule, I never recommend going against checklist/manufacturer guidance, But, in the sidebar below, I mention always having a diversion plan while in cruise. It could be as simple as hitting “nearest,” and then “direct” on your GPS navigator. It could be the closest 3000-foot runway, or the closest ILS. It also could be the cornfield just over the nose. And remember that the closest suitable airport may be the one you just departed.

If I had an unknown source of smoke or fumes that I was concerned could rapidly get worse, I would never knowingly fly away from my best divert options.

Also remember that the manufacturer’s checklist may concern itself primarily with disabling the malfunctioning system. It also may not reflect the latest guidance or equipment added since it was new. You’re a pilot, and you can get the airplane heading to an appropriate landing area and shut off firewall access at the same time.

Again, I am not saying do not follow the checklist, but maybe consider pointing the aircraft in the general direction of the safest landing point while you work through the first few steps.

In nearly every abnormal or emergency situation, the first thing to do will be to complete the memory items and/or applicable checklists. Some airplanes have varying degrees of guidance in these departments, so here are some general strategies and actions to take.

In nearly every abnormal or emergency situation, the first thing to do will be to complete the memory items and/or applicable checklists. Some airplanes have varying degrees of guidance in these departments, so here are some general strategies and actions to take.

If there are oxygen masks on board, now is a good time to use them while ensuring they are clear of smoke and fire sources.

If the source of the smoke or fumes is known, shut the system down or fight the developing fire with an extinguisher.

Get as much fresh, breathable air into the cabin as possible.

Plan to land. Your options are the nearest suitable airfield, the nearest airfield or the closest spot where it would be safer to land than continue being airborne. This is extremely challenging, dynamic and worth a whole article on its own.

Smoke and fume situations are truly some of most harrowing emergencies we can face as aviators. The best way we can prepare for these situations is proper training and having a plan. Even simple techniques like having an immediate diversion plan during cruise or proper, safe loading of the aircraft can move the needle toward a desirable outcome.

My very limited experience with discharging a fire extinguisher is that it made one hell of a mess. What’s it like to discharge a fire extinguisher inside a typical four seat cockpit? Will I still be able to see and breathe enough to fly the plane? I’ve generally thought of the onboard fire extinguisher as something to use in case of an engine fire on the ground, should I rethink that?

This is a great question. If anyone else reading this has discharged a fire extinguisher in the cockpit, please speak up because I think the input would be extremely valuable.

I have never actually discharged a real fire extinguisher, they use fake ones with water or other materials in training to simulate the experience. After watching a few videos online, my recommendation would be what it often is…it depends.

1. If you are solo in the aircraft, your efforts are more likely better spent getting the aircraft on the ground ASAP.

2. If the fire is growing so rapidly the fire extinguisher becomes your best chance to get on the ground safety, I would use it. It will make a mess, but the recommendation for fire extinguishers is generally to empty the bottle at the fire to ensure it is out. At this point, you are weighing the risks emptying the extinguisher and making a huge mess, covering instruments, creating difficulty breathing, reducing visibility, ect with using it partially and having the fire come back. This would depend entirely situation to situation.

One of the reason smoke and fumes is so scary is because every situation is different. If you’re flying a skyhawk in the Caribbean and you’re in the middle of the ocean, you might be more motivated to fight the fire rather than ditch miles out to sea. If you’re in the pattern you may find getting on the ground and hoping out is the better solution.

Like I said, I’ve only really worked through this in the hypothetical, but I agree 100% that the ramifications of emptying the bottle should be brought into this discussion. Hopefully someone who has seen this in action will having something to add.