Anyone familiar with accident investigation likely has heard the phrase “chain of events.” It refers to any number of factors contributing to the accident or its severity. Of course, the vast majority of accidents result from one or more mistakes made by a human, generally referred to as pilot error. Mechanical causes pose much less risk but, once they occur, can contribute to the pilot making a mistake in responding to the failure or mishandling the aircraft. An example of the latter might be the pilot who is so happy they made it to a suitable runway after an engine failure that they forget to extend the landing gear.

One of the best defenses against pilot error is standardization, followed closely by its first cousin, experience. Correctly performing tasks the same way every time is an example of standardization, while knowing when to go back and start over if a checklist is interrupted is a mark of experience. Standardization can be taught, beginning with primary training, but experience can be a hard-earned badge, often gained by—you guessed it—standardizing tasks and procedures, even in the midst of major distractions.

Put simply, we standardize our tasks and procedures to minimize risk. But minimizing risk doesn’t mean it goes away; even seemingly insignificant events can become the first link in the accident chain, especially when our experience level means we may not react properly as subsequent links are encountered.

Background

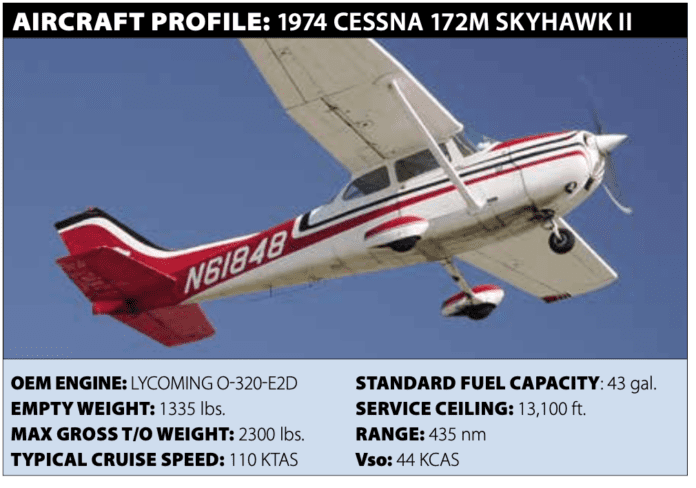

On October 28, 2021, at 1311 Pacific time, a Cessna 172M Skyhawk was substantially damaged during an aborted go-around and loss-of-control event in Ukiah, California. The solo student pilot (male, 43) was fatally injured. The pilot was making his second solo cross-country and fifth solo flight. His planning included a full-stop landing at Ukiah.

As the airplane approached Runway 15, a witness noticed it was “porpoising.” He watched as the pilot initiated a go-around, climbing out with its flaps deployed. Video footage captured the airplane during the initial climb phase of the go-around, showing the airplane reached about 60 feet agl before resuming a level attitude, still aligned with the runway. At midfield, it pitched down and descended until the airplane’s nose struck the ground, separating the nosewheel. The airplane continued down the runway; a second witness saw a cloud of dust appear at the end of Runway 15, and then watched as the airplane’s tail lifted up and the airplane rolled inverted, coming to rest next to a taxiway on the right side of the runway.

This accident likely would have been survivable if the pilot was wearing his three-point shoulder harness. According to the NTSB, he recorded much of the flight on an in-cockpit video camera, including a moment before takeoff when he remarked he had dropped his pen. Later, once airborne, the video records him saying he found it.

While reciting and performing the before-landing checklist, he was distracted “as the airplane flew close to a bird.” Subsequently, the pilot either did not verbalize the remaining checklist items or failed to perform them. Among the remaining items was confirming the seatbelts were fastened.

According to the accident pilot’s flight instructor, “…the pilot always wore his seatbelt and flying without it was not an option. The pilot’s wife also stated that he always used his seatbelt when driving and was insistent that others wore them too.”

Investigation

Airframe damage was limited to the vertical stabilizer, rudder, leading edge tip of the left wing and the windshield, which had shattered, plus the detached nosewheel. The propeller exhibited evidence of runway contact including tip curl and multi-directional gouges and scratches. Wing flaps were retracted, elevator trim was set for takeoff, and the carburetor heat control and corresponding air door were in the off positions.

One ounce of water was drained from the gascolator, and three ounces were drained from the left wing’s fuel tank drain. Both fuel tanks then were completely drained, and another three ounces of water were in the left tank.

Examination of the left tank revealed a leak had developed around the filler neck, along with extensive brown staining trailing aft of the fuel filler cap. The gasket sealing the filler neck to the tank had degraded and was no longer providing a seal. Silicone sealant was present in multiple areas inside the top wing skin, consistent with an attempted leak repair. There also was a buckle in the lower tank skin, creating a 0.1875-inch-deep, 2.5-inch-long and 3.0-inch-wide raised area. The buckled area inside displayed signs of corrosion.

Earlier on the day of the accident, a flight instructor noticed water in a fuel sample taken from the accident airplane during a preflight inspection. The instructor was surprised by the find because it was the first time he had seen water in a fuel sample from that airplane. The airplane and engine performed without issue on the ensuing flight.

Before departing, the accident airplane was topped off with fuel. The line technician observed the accident pilot checking the fuel quantity at the filler caps, and then collecting a fuel sample at the wing tank drains. A photo recovered from the pilot’s phone and taken 21 minutes before he departed showed a “fuel-check” sumping tool, held by the pilot, containing what appeared to be aviation gasoline. Below the blue fluid there was a small clear globule that appeared to be water.

The pilot used a cockpit-mounted camera to record video during the flight. During the landing flare, the pilot transmitted on the CTAF his intention to perform a go-around. As the airplane reached about 60 feet agl, a change in the stroboscopic effect of the propeller was recorded, indicating an engine speed change. The airplane leveled off, and the pilot said, “Whoa, whoa, whoa,” before the recording ended. The NTSB concluded the power interruption was caused by the engine ingesting water, resulting in the pilot aborting the go-around and opting to land on the runway. Instead, the airplane contacted the runway in a nose-down attitude, separating the nosewheel.

During the accident sequence, the pilot was partially ejected through the windshield. The airplane was equipped with three-point lap- and shoulder-belt restraints for the pilot seat. Examination revealed the shoulder harness was attached to the center lap buckle, but the lap buckle was found unlatched.

The lower section of the left instrument panel sustained forward bending damage. According to the NTSB, “A series of tests was performed to determine if the damage could be attributed to contact with the pilot during the accident sequence. The tests revealed that if the pilot had been securely buckled into his seat, he would not have been able to move forward and contact the damaged areas.”

Probable Cause

The NTSB determined the probable cause(s) of this accident to include: “A power interruption due to water-contaminated fuel, which resulted in the student pilot aborting the takeoff and landing hard. Contributing to the accident were a leak in the left fuel tank that allowed water to enter and damage to the fuel tank that prevented water from being properly drained during the preflight inspection.”

The NTSB again: “According to the pilot’s flight instructor and his spouse, the pilot was a strong advocate of seatbelt usage. Although the reason for his failure to wear a seatbelt could not be determined, it is possible that when he dropped his writing implements during the flight, he released his seat belt to recover them and failed to resecure it. When his pre-landing checklist was interrupted due to the proximity of a bird, he became preoccupied by the busy airport environment and did not finish the checklist.”

The problem with accident chains is twofold. One, we typically don’t know how long the chain is and, two, we don’t know which is its weakest link. That’s why we need standardization. Experience doesn’t hurt, either.