(Editor’s Note: This is the final contribution to a three-part series on going beyond the standard preflight weather briefing on your EFB.)

The contemporary electronic flight bag (EFB) is truly a “how did we ever live without this?” kind of tool. It can put just about any text or imagery on its display at the tap of an icon, tell us where to look for traffic and display the observations from ground-based Nexrad weather radar sites. One thing an EFB can’t do, though, is respond to questions you may have about your briefing.

That’s when you need additional resources, many of which were highlighted in the two articles appearing in the August and September 2023 issues. One other thing you may need is real-time information on thunderstorms. But your EFB can’t give you real-time information, thanks in part to the weather data that easily can be 20 minutes old. A lot can happen in a thunderstorm in 20 minutes.

The best strategy without airborne radar is to stay in VFR conditions, which means that sometimes your only option is to fly toward the bluest part of the sky. That isn’t foolproof, especially under an overcast. Storms can build ahead of you, unseen, and lighting conditions can lure you into trouble. Once over warm and humid Ohio in a Piper Warrior, I thought I was avoiding everything visually until I saw cloud-to-ground lightning at 12 o’clock just a couple of miles ahead. I didn’t hesitate: I did a quick 180-degree turn and landed at a very pretty, though wet, nearby airport.

Weather Radar

Weather radar isn’t perfect, either. It’s heavy and uses a lot of power, so it is only found on heavier aircraft. The smallest planes I have seen with weather radar are Cessna 210s and larger propeller-driven singles like Malibus or Caravans. In most jets, including transports, there is a crew of two, but in the smaller installations a pilot has to run the equipment while flying the airplane. That is a handful, especially without an autopilot.

Formal training for the single-pilot environment often omits weather radar. I’ve been to a dozen or so simulator training events, some lasting more than a week. There is so much required material, I’m sure the phrase “drinking from a firehose” was invented by someone sitting in a simulator. Aircraft systems, FARs, ATC procedures, checklists, avionics and all of the required maneuvers make for full days of study. There is no time to fool around with the radar in the simulator itself, and while there may be an optional groundschool course, most pilots don’t have time. A recent training manual from one of the big simulator facilities has only two pages on weather radar.

I was lucky enough to fly with a more experienced pilot who taught me the basics, and as someone of a scholarly bent I did a lot of self-study. Here’s some of what I learned.

In-cockpit weather detection tools come in two basic flavors: tactical and strategic. Other than your two eyeballs looking at a storm in visual conditions, the only real tactical thunderstorm detector is airborne weather radar; everything else should be considered strategic in nature. What’s the difference?

Think of a tactical device as one you want to use when you’re up close and personal to the storm. A strategic tool, like Nexrad or the Strike Finder pictured, is best used at a distance to highlight and plan for areas you want to avoid, and to help you make adjustments to your route as you go around the entire area.

The main reason for this is that a Nexrad presentation is truly a historical document—it depicts what the weather looked like several minutes ago, when the data was captured, and before it’s processed and transmitted from the observing facility to your iPad. That can easily require 20 or so minutes. A thunderstorm can change dramatically in 20 minutes. Nexrad timestamps reference transmission, not acquisition.

An sferic device, meanwhile, operates in real-time, up to a point. That point is its retention rate, which the pilot can’t adjust except by clearing the screen and allowing it to repopulate. The rate at which it plots new lightning strikes is a data point itself.

Sferic devices detect and plot the electricity in lightning, the presence of which defines a thunderstorm. But turbulent and/or rainy weather may not be discharging static electricity. Another characteristic is that range is an estimate, based on signal strength. A particularly strong storm will be plotted closer than a weaker one, and vice versa.

As a rule, Nexrad is better than an sferic, which is better than nothing. — J. B.

Theory And Use

The basic idea of radar is in the name, which is constructed from RAdio Detection And Ranging. The unit sends out a narrow beam of radio energy, and waits to see if it bounces off something in the distance. Not much energy gets reflected: In the first radar measurement of the distance to the Moon, the return from a 600 kilowatt signal was just three watts.

More useful to pilots is the distance to a drop of water. Energy striking the water ahead bounces back, and electronic wizardry displays the bearing and distance in the cockpit.

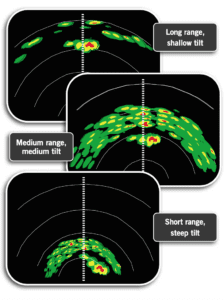

Ten minutes is almost always enough time to notice that there is something ahead and make a plan to miss it; for most of the flying I’ve done that works out to be 40 nautical miles. That determines the range. Looking 80 miles ahead gives some idea of a system’s extent, and looking 20 miles ahead might help navigate a narrower gap.

On one of my first flights with a radar set, I got more and more concerned about the persistent thunderstorm over Boise. That’s what all that red meant, right? No, it meant that the buildings of downtown Boise were reflecting radar energy. Tilting the antenna up avoided the ground return. The air above was clear.

The best rule-of-thumb that I know is to tilt the radar down so that the upper third of the screen shows the returns from the ground. This way you know that the unit is working, and that it’s not pointed up at the Moon. The picture ahead will change a little as different terrain comes into view, but generally the bottom two-thirds of the screen stays clear. If there is something like a storm cell in the air ahead, its image will start to move down the screen and toward you like an old video arcade game’s alien invaders. One pilot I know actually calls them “aliens.”

Most modern systems are automatic for everything else. The two most common choices are labeled something like “weather” or “ground.” This being aviation, those get abbreviated to WX and GND. Ground mode is useful when departing mountain airports: it can be an independent verification that you’re still in the valley.

Remember, the radar screen is oriented with aircraft heading, not with track, so a cell that appears to one side might be right where you’re heading. The old rule that if the bearing to something is not changing, then you will hit it still applies.

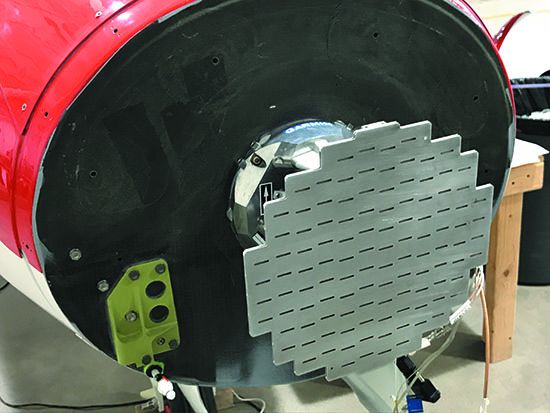

The best spot for a radar antenna is in the nose, so in a single-engine airplane, the radar is carried in a wing pod. That limits the size of the antenna, which means it receives less data. But it’s still useful.

Sferic Devices

A Stormscope is a lightning-detection device, sometimes referred to as an “sferic.” (The name is probably trademarked or copyrighted, but the technology has changed hands so many times, it’s hard to know whom to credit!) A similar product is the InSight Strike Finder. Both are relatively inexpensive, lighter than radar and use less power, so it was and may still be attractive to pilots flying high-performance piston singles in the age of in-cockpit Nexrad.

There are dozens of variations in how these displays work. If you are flying something with this kind of display, there is supposed to be a supplement to the POH describing its use. Read it. Study it. But here are some of the basics.

The first thing to select is the range. I find that the same rule of thumb applies: Five to 10 minutes ahead gives enough detail, but also leaves room to decide how to maneuver. Sometimes the only choice is to fly toward the bluest sky…

And the bluest sky might well be behind the airplane! One of the advantages of some Stormscope displays is that a pilot can look at what is happening behind the airplane in a 360-degree view. That can be useful for information on planning your escape.

It is possible to clear the display. Starting with a clear screen lets you judge how active the systems are.

It is possible, but difficult, to use weather radar to “see” other airplanes. This is more for fun than for real-world traffic awareness, but it’s an exercise that helps you understand what radar can do.

Airplanes are pretty small, so set the gain—that is, the transmitter power—to its maximum. (Keep an eye on electrical load while you do this.) The gain control was easier to find on older units where it was a dedicated knob, but with automatic processing you might need to go through a few menus to find it. Set the range to something close, like 10 nm.

Then, tilt the antenna up. Use the Rule of 60: One degree of heading means one mile off-course when 60 miles away. An airplane 2000 feet directly above you is a third of a nautical mile away. At six miles, that’s a little over three degrees. Setting the tilt there means that airplanes above will be in the beam.

If you find one, it will be a small smudge that jumps closer with each antenna sweep. If you want to get really nerdy you can use the size and direction of the jump to estimate its course and speed.

ATC

Air Traffic Control radar weather depictions keep improving, but that radar is designed to see airplanes rather than precipitation (see sidebar). The only clearance you’ll get is a clearance to deviate: they cannot and will not tell you where to go. Sometimes a controller will say something like, “I’ve had a lot of airplanes go around to the north.”

Also, ATC keeps a close eye on any airplane deviating toward active military airspace or sector boundaries. This is another factor to consider when using your own radar.

But don’t be afraid to ask if the airspace you need is available. I’ve had some very nice tours of restricted areas while flying toward the bluest sky. If the airspace is not busy, ATC will gladly let you in. In the western U.S., some of the military airspace is in use continuously, and civilian ATC won’t touch it. Sometimes it’s possible to contact the controlling agency to ask for clearance, but don’t count on it.

Our eyes are the best thunderstorm avoidance tools available. It’s very simple: Stay in visual conditions, and you’ll never enter a thunderstorm. If we want to get tactical, airborne radar is the way to go. Strategic tools vary, but they all tell you what to avoid.

Jim Wolper is an airline transport pilot and retired mathematics professor. He’s also a CFI with single-engine, multi-engine, instrument and glider ratings.