It’s that time of year again in the Northern Hemisphere—finally!—when many pilots turn to scraping off all the rust their skills accumulated over the winter months and set their sights on flying to fun places offering shirtsleeve weather. One popular destination is always a local or regional fly-in, and literally thousands of pilots save up their nickels for the big, international events like SUN ‘n FUN Aerospace Expo (KLAL, April 8 through April 19, 2024) or EAA AirVenture Oshkosh (KOSH, July 22 through July 28, 2024). Other events, like the recently concluded AOPA Buckeye Air Fair in Arizona, are not as large as SnF or Oshkosh, but remain major attractions.

I’ve flown into my share of these events over the years, with both good and bad experiences. The good include a “Nicely done!” from an SnF controller; the bad involved an experimental amphib cutting through the arrival corridor at my altitude. At a recent local event on a nearby island’s grass strip, my passenger and I touched down, rolled out and parked smoothly, only to be greeted by some glum faces. Turns out there was a Cessna 172’s tail sticking out of some heavy brush toward the end of the runway. I don’t recall what happened, but the airplane wasn’t flying off the island that afternoon.

Procedures

One thing these and other fly-in events have in common is their greater-than-usual numbers of pilots and aircraft. Another common characteristic is that many of these pilots want to land or take off at roughly the same time. At best, that can mean a delay or two getting in or out. You don’t have to be an air traffic controller to figure out the worst.

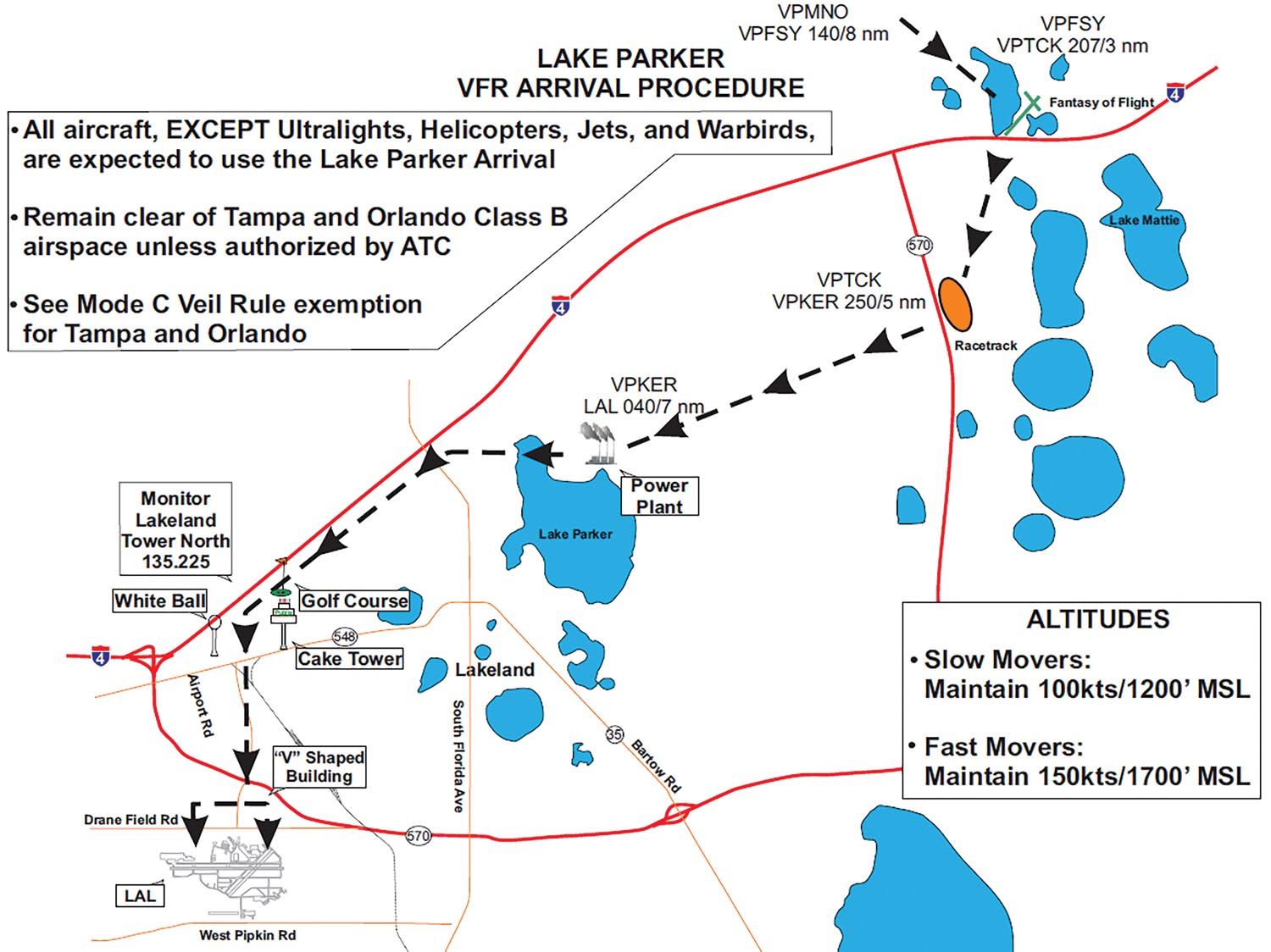

The good news is there often are specific arrival and departure procedures designed to keep traffic flowing while maintaining separation, albeit perhaps not to the same standards you may be accustomed. Each event’s procedures differ, but their sponsors typically put together some sort of guidance for pilots flying in, even if it’s only a single page of local comm and nav frequencies, a crude drawing and parking instructions.

Of course, the granddaddy of air show fly-in procedures is EAA AirVenture, where the 2023 documentation came to 32 pages. (In years past, this was a formal Notam. For 2023, it became a mere “notice.”) The 2024 edition of the SnF Notice runs to 23 pages.

In general, the published arrival procedures at these two fly-ins will have you self-sequencing into the flow of aircraft toward the airport. Controllers on the ground will try to manage things, but they often misidentify airplane types—it’s easy for one low-wing airplane to implement an instruction meant for another low-wing. And although each procedure has a recommended altitude and airspeed, it’s rare that any of the pilots flying near you have logged any recent slow-flight practice. For example, it shouldn’t be that difficult to maintain 100 knots and 1200 feet msl, but it is for many. Straight and level should be the easiest part of flying these arrivals.

Considerations

Understanding the arrival procedure is a very important part of flying into a fly-in. But that’s in addition to the other stuff you need to think about as a pilot. What other stuff? Fuel for one; weather for another.

It’s not the least bit rare for the destination airport to close unexpectedly. When it does, it’s usually because someone forgot to put down their landing gear and is blocking the runway. What happens next is up to you, but the arrival flow will be directed into a VFR holding pattern. Major fly-ins will have guidance on where and how to enter VFR holding, which will differ by location, but generally will call for orbiting a visual checkpoint like a lake.

At the major events, airport operations will clear the runway as soon as possible consistent with emergency services’ requirements. It doesn’t do any good to ask on the frequency how much longer it will take.

Another reason for the airport to close can be poor weather. When visibility or cloud cover drops enough to make things IFR, there’s little anyone can do about it. Although I’ve seen some airports adopt a generous visibility observation, you can’t count on it. The only good news in that situation is following the guy or gal in front of you always can be a good policy.

Both closure reasons are why we all should arrive at the initial fixes for these arrivals with plenty of fuel. If you’re arriving from a few hours away, it’s a good idea to stop an hour or so out to top off, freshen up and get new weather information before relaunching on a final, much shorter leg.

If you plan it right, many airports/FBOs offer fuel discounts if you’re going to a big show, and may even have free food available. Check the event sponsor’s website for participating fuel stops or, if all else fails, pick up a phone and call ahead. Even if you have plenty of gas, the smart thing in a temporary airport closure situation may be to divert to a nearby runway to wait out the delay instead of circling a lake for an hour. Before you even take off is a good time to nail down your ideal divert airport, a decision that easily can be based on rental car availability alone.

Prepping And Practicing

If all the foregoing seems intimidating, it probably should: Flying into SnF or AirVenture isn’t something you should approach lightly. It goes without saying that the airplane should be in good shape, but so should the pilot. How can we make sure our skills are up to the task? The same way we get to Carnegie Hall: Practice.

But what to practice? Slow flight, for one. Historically, some nummies apparently can’t tell the difference between 60 knots and 90 knots on their airspeed indicator, but you’re better than that. (If you feel the need to grab an instructor for this, you’re doing it right.) They spend their time jockeying pitch and power, but end up working too hard, with obvious excursions of both, leaving the planes following them with little choice but to follow along.

Go out and find the pitch/power combination that results in your desired airspeed. Write. It. Down. Then maybe tape it to your instrument panel. You’ll probably find that an extra inch or 100 rpm is needed to compensate for the people and stuff you’re hauling in for the show, but that’s relatively easy. Your job is to know what settings give you the desired performance, and you have to have a place to start.

Low-speed handling is something else you need to practice. Remember that stall speed and angle of attack increase when banked and maintaining altitude, but both increases can be minimized when descending. A good way to practice this is to slow to your airshow approach speed on downwind, and fly the traffic pattern at that speed until short final.

Another thing to practice is spot landings. Arrivals at SnF and AirVenture often are asked to land on or beyond certain runway features—the green dot painted on the runway, for example. You should probably practice for that, too. For planning purposes, you may be expected to approach and land with other airplanes ahead of you or in-trail. For example, if you’re the first in a gaggle of three, you’ll be asked to land beyond a dot. The #2 airplane might be asked to land on the dot while Tail-end Charlie touches down on the numbers. If you’re #1 in the gaggle, keep it rolling—ATC likely will want you to exit the runway at the end.

Departing

I’ve focused this article on arriving at these air shows, but how you depart can be just as important. You want to follow any published procedures, which generally will have you flying the departure runway heading for a few miles at or below a certain altitude. Once clear of the show’s airport, you’re more or less free to turn on-course and climb but, just as with arrivals, it’s likely there’s someone out there with the same plan as you. Departing AirVenture last year, a V-tail Bonanza and I ended up flying in loose formation for about 45 minutes.

If you’re looking for an IFR clearance but don’t have an STMP reservation, you’ll need to motor down the road a bit before anyone will give you one. The 2024 SnF Notice has a slew of details on where, how and when you can pick up an IFR clearance. The same has been true for AirVenture in recent years, also. Of course, departing VFR isn’t an option when the airport goes IFR. Neither the AirVenture nor SnF Notices include information on special VFR operations—when weather at the two airports goes down, nothing except an IFR clearance will get you out.

Fly-ins are not the only events attracting high aircraft traffic volumes. Almost any major event—sports championships, Nascar races—can overwhelm local ATC and runway infrastructures at times. In response, the FAA implements special traffic management programs (STMPs) for arrivals and departures for these events, principally to accommodate IFR operations. When an SMTP is in effect for specific events, the FAA requires users to make arrival and/or departure reservations at affected airports. Note that STMPs typically are used during SnF and EAA AirVenture fly-ins and are part of the overall guidance.

Fly-ins are not the only events attracting high aircraft traffic volumes. Almost any major event—sports championships, Nascar races—can overwhelm local ATC and runway infrastructures at times. In response, the FAA implements special traffic management programs (STMPs) for arrivals and departures for these events, principally to accommodate IFR operations. When an SMTP is in effect for specific events, the FAA requires users to make arrival and/or departure reservations at affected airports. Note that STMPs typically are used during SnF and EAA AirVenture fly-ins and are part of the overall guidance.

In the bad old days, pilots used a touchtone phone to enter and manage a reservation request and rarely spoke with a human, but the process has been automated and is accessible online at www.fly.faa.gov/estmp/. Again, this is only for IFR operations, and an STMP confirmation number must be entered into the flight plan’s “remarks” block. No STMP reservation is needed for VFR operations, but that doesn’t mean there won’t be any delays at peak times.

Other Shows

I’ve concentrated this article on AirVenture and SnF, since their procedures are the most detailed, and the two shows also are the most popular. Other fly-ins aren’t nearly so complicated, mainly because they don’t have the same traffic levels. But the same caveats can apply, especially those suggestions involving slow flight and spot landings.

Finally, many smaller events can be at grass runways—your airplane’s manufacturer may have specific recommendations when operating to or from soft fields, like using flaps for takeoff. Do your research, plan ahead, watch the weather and get some practice. You’ll do fine.

One of the more entertaining and frustrating aspects of flying into major air shows is the guy—and it’s always a guy—who pops up on the frequency asking for help in flying the arrival procedure. It’s a giveaway that the pilot doesn’t have the Notam available and probably hasn’t read it. As connected as our cockpits can be these days, it’s unlikely we’re equipped to download a 32-page PDF document while airborne. Even if it was, starting to read it is something we should have done a week or so earlier.

One of the more entertaining and frustrating aspects of flying into major air shows is the guy—and it’s always a guy—who pops up on the frequency asking for help in flying the arrival procedure. It’s a giveaway that the pilot doesn’t have the Notam available and probably hasn’t read it. As connected as our cockpits can be these days, it’s unlikely we’re equipped to download a 32-page PDF document while airborne. Even if it was, starting to read it is something we should have done a week or so earlier.

Since the airplanes arriving before and after you may be parking on either side of you, if your arrival made it obvious you don’t know what you’re doing, prepare to be embarrassed. I have a mantra: Get the Notam. Read the Notam. Fly the Notam. There’s really no substitute.