I am of the opinion that thunderstorms are the most challenging weather condition to fly in regularly. Most other hazards have solid mitigation strategies or present such a high level of risk that the flight must be scrapped. Of course, this all vastly depends on your mission.

Moderate turbulence, for example, does not typically present hazards that would put your flight at undue risk, but I certainly would not take a first-time flyer in such conditions. Low visibility can cancel or change plans, and icing always takes careful consideration by planning your outs. High winds are usually accurately forecast, and only truly become an issue if a landing is forced beyond the ability of the aircraft or the pilot.

Several factors set thunderstorms apart from the above when assessing risk and trying to craft a plan that does not involve a frustrating drive home from the airport.

HAZARDS

Thunderstorms present several hazards to aircraft large and small. Hail, turbulence, lightning and tornadoes top the list. One of the biggest challenges is determining the severity of whatever storm you are looking at. This is where it comes in handy to have a trusted local news channel and supplement your briefings with the local weather forecast. As easy as it is to access briefings online, fewer and fewer pilots are calling certified weather briefers. Mostly this is fine, but even the experts can struggle to interpret the constantly changing conditions that lead to thunderstorms. Local weather can usually give you a more precise forecast than a convective outlook, and an idea of how widespread the storms will be.

The only true way to avoid the hazards stated above is to simply avoid the storm itself. The FAA’s Advisory Circular AC 00-24C, provocatively titled “Thunderstorms,” provides a great list of dos and don’ts when avoiding thunderstorms. One of the most important items is the following: “Do avoid by at least 20 miles any thunderstorm identified as severe or giving an intense radar echo. This is especially true under the anvil of a large cumulonimbus.”

Twenty miles may seem a bit extreme at first. I have a vivid memory of when I was instructing, sharing the pattern with four other airplanes from the flight school. It was a high-overcast day, with nice, calm weather. A perfect day to practice some landings. Unbeknownst to us, a thunderstorm had popped up about 10 miles west of the field. Eventually, the tower notified us that a moderate-to-severe storm was in the vicinity of the field and asked our intentions. Like all conscientious instructors concerned with demonstrating good aeronautical decision-making, we landed and taxied in. We had just buttoned up the aircraft and gotten inside before it was absolutely pouring rain.

It always struck me how calm it was prior to the storm. No sign of wind shear or hail, and even the initial precipitation level did not seem any worse than a light afternoon shower. If one is not careful, experiences such as these can cause normalization of deviance.

Every time I see a storm, I remember that day and how calm conditions were a few miles away. If you think about trying to beat out a storm and want a good PSA on why this is a risky train of thought, use your favorite search engine to find some pictures of aircraft that have been introduced to hail. It is not a pretty sight.

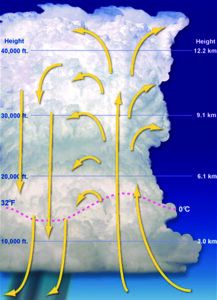

Long story short, the hazards of thunderstorms are significant. Additionally, the storms are quick to develop and, as I mention later, unpredictable. And unless you can climb over the tops, neither the aircraft’s nor the pilot’s capability can guarantee a safe outcome if you are caught in one.

Some pilots like to distinguish between what they might call strategic thunderstorm avoidance—keeping storms at a distance—and close-up tactics for when that’s not possible, or you just want to find the quickest, smoothest ride through some widely scattered storms. What are the differences?

STRATEGIC

Another way to think of strategic thunderstorm avoidance is as a matter of time and place: If you know when and where the storms are or will be, you can arrange to not be there. Specifics can include departing earlier in the day, departing the previous day, or waiting for them to pass you by before launching. At the same time, you should be able to outrun them, or perhaps maneuver around them, even if it requires a significant routing change. I’ve always found ATC eager to accommodate when it comes to on-the-fly changes.

TACTICAL

When strategic options won’t work, or the storms catch you by surprise, there are still some things you can do. One is to study the storms’ movement over time: there’s nothing you can do to move them out of the way, but you can leverage their motion and your relative speed advantage. Primarily, though, tactical thunderstorm avoidance involves the Mk 1, Mod 1 eyeball, and staying in visual conditions as you weave your way through the minefield. If you can’t stay visual, go somewhere else. Always have an out, which likely will involve a 90- or 180-degree turn. Be careful that your exit door doesn’t close behind you. — J.B.

UP IN THE AIR

Modern technology has made thunderstorm avoidance technology more accessible to all pilots. In a similar vein as improved avionics and flight into known icing technologies, understanding the limitations to new technology is just as important as learning how to use it. Whether airborne or ground-based, weather radar is the most common tool for avoiding thunderstorms. Both have their limitations.

Airborne Weather Radar: I chose airborne weather radar first because it is probably the most accurate source of what is actually happening in front of you. Color-coded rain density can indicate storm severity, typically ranging from green (light) to magenta (extreme). Many modern radars incorporate a lightning strike indicator, which, true to its name, depicts lightning strikes as they happen. Used together, these give the best real-time picture of the weather in front of you. Like much in life, airborne radar is a great asset but far from perfect.

One limitation of airborne radar should be obvious: The aircraft and its radar antenna need to be facing the weather. There’s nothing more frustrating than not knowing if you can accept a vector because the storm is outside the lateral range of your radar. Additionally, airborne radar is subject to attenuation, which occurs when the reflection prevents the radar from detecting additional cells that lie behind the first cell or two. Essentially a cell can cast a radar shadow, which can mask much larger/dangerous weather behind it.

Radar is also subject to user error. The lateral movement of the radar is a constant sweeping motion, but due to the aircraft’s changing attitude, the pilot must control the tilt of the radar. There are several tips and tricks in perfecting this art, but rather than give broad advice that may not apply to your radar, I will just advise everyone to consult the manual for any equipped aircraft you may fly.

The last major limitation of airborne weather radar is caused by the variation of precipitation reflectivity. Wet hail, rain and wet snow are more reflective than their dry or frozen counterparts. Many thunderstorm tops are composed of low-reflective precipitation, which presents some difficulty since painting the thunderstorms is sort of the whole point. Luckily for us, there is another tool available to us that substantially mitigates these limitations.

Part of the challenge of flying in convective weather is its unpredictability. While it’s easy to forecast thunderstorms will be present on any given afternoon, trying to guess their movement, intensity and size is a different beast entirely. Many summer afternoons contain the correct recipe of lifting action, instability and warm, moist air. Recognizing the common types of thunderstorms can help you make the decision to go around, wait it out or drive:

*Single Cell: A single-cell (or common) thunderstorm cell often develops on warm and humid summer days. These cells may be severe and produce hail and microburst winds.

*Thunderstorm Cluster (Multi Cell): Thunderstorms often develop in clusters with numerous cells. These can cover large areas. Individual cells within the cluster may move in one direction while the whole system moves in another.

*Squall Line: A squall line is a narrow band of active thunderstorms. Often it develops on or ahead of a cold front in moist, unstable air, but it may develop in unstable air far removed from any front. The line may be too long to detour easily around, and too wide and severe to penetrate.

*Supercell: A supercell is a single, long-lived thunderstorm which is responsible for nearly all of the significant tornadoes produced in the United States and for most of the hailstones larger than golf ball-size.

Preflight planning is the first line of defense, but due to the factors listed above, we can end up navigating thunderstorms without the tools available to us on the ground.

NEXRAD

Next Generation Weather Radar is a network of 160 high-resolution Doppler radars jointly operated by the National Weather Service, the FAA and the U.S. Air Force. Through a myriad of methods, you now can access Nexrad in your airplane easier than ever. Nexrad can depict precipitation intensity, winds and atmospheric movement. You typically can select composite or base radar to get a clear picture of the weather you are navigating.

A huge advantage to Nexrad is the ability to see the big picture. This helps mitigate radar attenuation as well as the line-of-sight limitations of traditional radar and allows you to plan further ahead. The ability to select the composite display can prevent errors due to tilt, and Nexrad does not have any issues detecting less-reflective precipitation. It almost sounds like the perfect system, right?

Except for one word: Delayed. It might be one of the most hated words in aviation. It is also the biggest pitfall of Nexrad. The data you are looking at may be 15-20 minutes old at any given time. Remember earlier when we were talking about how unpredictable thunderstorms are, and how rapidly they can change? Not exactly ideal for your thunderstorm risk mitigation tool to give you old news. The NTSB warns pilots that even though 15-to-20-minute delays are atypical, the age indication from the cockpit should be taken with a grain of salt.

Another resource available in the fight to not fly into a thunderstorm is ATC. While the Aeronautical Information Manual does plainly state, “Don’t assume that ATC will offer radar navigation or guidance around thunderstorms,” I have found that even in busy airspace, ATC will do their best to accommodate deviations and provide the most recent favorable routing. Ideally, other aircraft will be blazing the trail and giving Pireps along the way.

That said, ATC is also looking at potentially old data. There are several recorded incidents where an aircraft inadvertently entered a storm that was not painting on ATC’s radar. Remember, though, they are not in the cockpit with you. Do not let them fly your aircraft. If you feel something is unsafe or requires deviation, say so. Giving options and having a plan ahead of time will help grease the wheels when asking for help.

ALL TOGETHER NOW

Using both Nexrad and airborne weather radar together provides the most comprehensive and up-to-date information on convective weather around you. No matter what technology you have on your aircraft, the best tool available to you is good planning and ADM. Despite the storms themselves being unpredictable, the recipe is not. If afternoon storms are on the menu, aim for a morning flight or delay until the evening. If you choose to navigate storms, it is critical to remember that radar returns indicate precipitation, not turbulence.

Given the choice, it is always better to circumvent the storms or be on the ground when they pass by. Note how this article does not include what to do if you do inadvertently enter a storm…prevention is better than the cure.

Whenever I know that I will be dealing with convective weather, I always make sure I have two things in excess: time and fuel. The combination of fuel and time means options. Options to go around the storms, or potentially land short if the situation requires. There is always a hesitation to deviate from the plan, but some of my most enjoyable experiences in aviation came from times where I ended up somewhere unexpected.

The Helicopter Association International created a Land and Live pledge, primarily for helicopter pilots and operators but also applicable to fixed-wing drivers, after a slew of fatal rotorcraft accidents that involved inclement weather. While airplanes may have more limited options for unplanned landings, pulling up short of the weather can be a lifesaving choice. At the same time, and unless the storms are so fast you shouldn’t even think about getting near them, you easily can circumnavigate them under typical conditions. After all, you have an airplane.

Ryan Motte is a Massachusetts-based Part 135 pilot, flight instructor and check airman. He moonlights as Director of Safety when he isn’t flying.