Why would I want to read about that aircraft accident? I already know what happened there, it’s obvious: I heard all about it from some guy.”

Oh, do tell.

I was listening to a pilot tell a couple of us about an accident where the plane flew into the ground—CFIT. Everyone lived, though the aircraft was written off.

The pilot-storyteller said, “I know exactly what happened. The guy forgot to change his altimeter from 29.92 to the local altimeter setting during descent and that day, I remember, the local setting was I think 30.20. The guy was flying in clouds, descending to the DA, but because he had 29.92 set, he was lower than he thought and hit the ground.”

I cogitated on this, cleverly using both side of my brain (the inside and the outside). I was confused, and felt a case of either ground hypoxia or surface spatial disorientation (SSD) coming on.

Finally I said aloud, timidly, in kind of a mush-mouthed “mitigated speech” kinda voice, “Uhh, wha—what about that old saying about altimeters, ‘High to low, look out below?’”

Because I was thinking that the guy accidentally had a “low” setting in his altimeter, 29.92, but flew into a “higher altimeter setting” (30.20) airport, so wouldn’t he be higher above ground level than if he had the correct setting? That’s what I was thinking.

The storyteller bristled, “Just go sit in a cockpit and fool with the altimeter—you’ll see!” So I slunk off to fiddle with an altimeter, dreading to see the embarrassing outcome, figuring I was wrong, I should have known it was “dial in a low number, you get a low altitude readout, of course you’ll crash because you’ll be flying at a lower altitude above ground.”

In this case, a Christmas miracle: I wasn’t wrong. Try it your own self—dial the altimeter to a higher setting, watch the indicated altitude go up. Dial it down to, say, 29.45, the altimeter indicates a lower elevation. A “too-low” altimeter setting could cause “CFIC” (controlled flight into clouds), but not CFIT.

Looking It Up

Now I was intrigued, and I looked up and read about that particular accident. The pilot crashed not due to a “too-low” altimeter setting. But the accident’s probable cause was still pilot error. The pilot saw the runway lights when he reached the decision altitude (DA), just under a low ceiling, looked back inside the cockpit, then looked back outside, didn’t see the runway environment, didn’t go around, continued to descend and BAM—CFIT.

Aha!—I had found the reason for the crash. And the lesson for me, this time, was knowing when I should execute a missed approach.

Accident reports give me something to do, too. For example, I can chair-fly a missed approach. “Oh, those are easy,” one might say. Or worse, “I remember I used to have to chair-fly when I first started flying, but I don’t do that anymore.”

Really?

Be honest—when was the last time you shot an approach to no-kidding minimums, at night, in the weather, didn’t break out and had to go missed? Was it in the ‘90s? (The 1990s—we’re not talkin’ balloons in the 1790s here, like Montgolfier in France. Plus, I’ll bet going missed in a hot-air balloon makes for a lot less workload than in a jet.) Maybe chair-flying it once or twice before strapping on the jet wouldn’t hurt, ya know?

Writing It Down

I recently went through training for a type rating, and “It’s simple to do a missed approach” was the attitude of one instructor. Not for me, I told him. I had him read all nine or eleven in-cockpit steps of a missed-approach out to me so I could write them down and chair-fly them. He did read them, but acted like he was going way, way beyond his job description, really going the extra mile. His attitude was, “Okay, you can write them down if you want, but—ha, ha—who would need to do that?” Me, that’s who. I was the one who had to pass the checkride.

For example, the steps for a go-around/missed approach in the Cessna Citation II: Throttles to takeoff thrust, flaps to takeoff and approach setting, gear up (with a positive rate), landing lights and ignitions off, flaps up at V2 + 10, autopilot on, etc. etc, push this button, push that button, talk to ATC, turn to this heading now; no, not with the yoke because the autopilot is on, use the little knob down there in the dark by your hip, knick-knack paddywhack, give a dog a bone. It’s a super-busy time. Any honest pilot knows this. And what if it’s a circling approach on top of all that? At night? Yikes, unless I’ve been chair-flying the crap out of it.

VDP Calculation Motivation

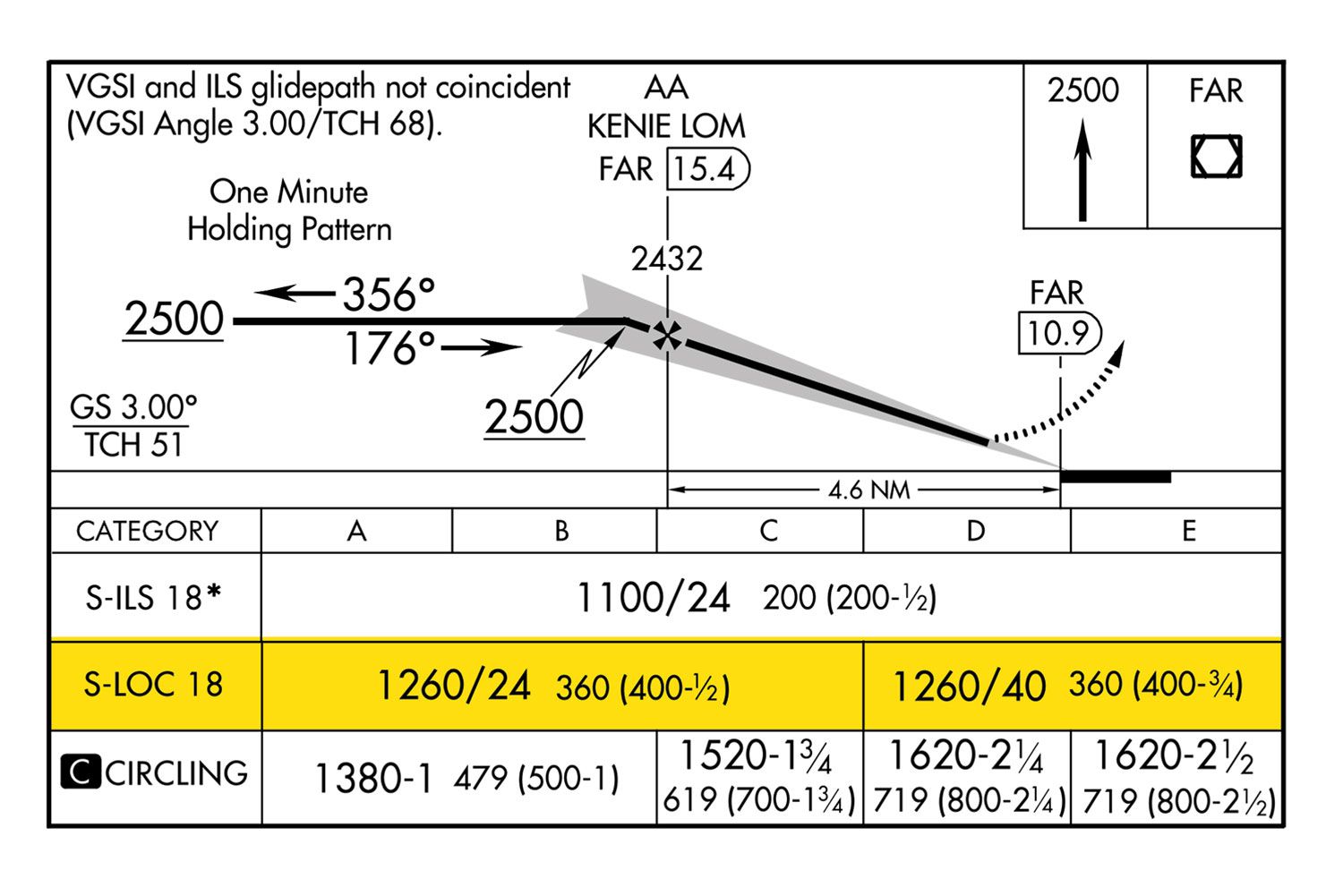

As we know, the accident discussed earlier wasn’t caused by an incorrect altimeter setting. Instead of reminding me to dial in the correct one, an accident report may motivate me to review how to calculate a visual descent point, VDP, when one isn’t published, so I don’t go below the minimum descent altitude (MDA) until I get to the VDP, or so I don’t fly past the VDP in the weather, break out, see the runway or runway lights and then make a too-steep dive at it. As an example, let’s look at the ILS or LOC Rwy 18 procedure at my home plate, KFAR, the Hector International Airport in Fargo, N.D. (Fargo, like the movie, but even colder. Up here, we measure temperature in “degrees Fargo.”)

The ILS is Tango Uniform, so we’re only using the localizer tonight. The MDA is 1260 feet msl, which turns out to be 360 feet agl. To calculate the VDP, divide the MDA’s agl value by 300, and that’s the distance in nautical miles from the runway you can begin to descend in visual conditions. In this case, 360 divided by 300 equals 1.2 nautical miles from the runway. Be careful not to confuse this distance with DME from the localizer transmitter or some other facility, or GPS distance from the airport center.

If I drop down to the MDA, fly in the weather past this self-calculated VDP to, say, 0.5 nm from the runway and then see the runway and try to land, what is my glidepath angle? The technical aeronautical term is “way the heck too steep” unless I shift my aiming point down the runway a ways. Also scary—I fly down to the MDA on a clear night, for example, level off, see the runway ahead clear as can be, and start down before the VDP. This will give me a “drug-in” final (drugs are bad) at best or a “tree landing” at worst.

Maybe I can/should think of the VDP as the decision point on whether to go missed—if I’m not in a good position to land with the runway in sight at the VDP, go missed. That’s a good plan. Of course, execute the missed approach as published (yes, no turns before the published MAP) or fly on vectors.

On every approach, we should be thinking we might have to go missed. Sometimes it’s not the weather, but maybe someone has a flat tire on the runway and closes it. (I can be cleared to land but discover there’s—surprise!—an aircraft sitting on the numbers. They blend right in like camouflage sometimes, don’t they??)

Experience Doesn’t Matter

Reading about experienced, high-time pilots who mess up is instructive and humbling for me. One of the things that comes across is that there isn’t a “safe” amount of experience or number of ratings, or number of hours that will prevent me from having an accident.

A pilot with thousands and thousands (and thousands) of hours can take off from or land on the wrong runway, take off with control locks installed or the parking brake set, miss crucial items on a checklist, or land long and hot on a slick runway, going off the end. Pilots who even build their own airplanes crash sometimes. Egads.

Flying personal airplanes is where some really, really experienced pilots get killed. Airline flying is way safer—two pilots, dispatchers, duty-time limitations, etc.—redundancy up the ying-yang. General aviation? Nope, and I know this, so I read about accidents.

When I was flying the T-38 as an instructor in the US Air Force, we’d read about accident reports (written on real paper) and talk about them with our students. We had to—it was part of the training syllabus. We’d give the student the lead-in-to-the-accident scenario, and ask them what they’d do.

Nowadays, a pilot can type in any search criteria they want and get multiple hits. I can read about what led to the crash—overshooting the turn to final, landing too long and hot on a slick runway, and on and on. And then I can think about what I should—and hopefully will—do differently.

Sometimes there’s a very interesting little thing that happened that may never happen again—but it might. For example, a pilot jumped out of one aircraft after parking it, ran and jumped into a new aircraft to reposition it to another airport. He was taking off from the right seat, solo, at night, in a hurry, because he wanted to get home—but there was an unseen control lock in the left yoke. He missed it—the flag was broken off, so it was just a small black pin in the yoke shaft, and he didn’t do a “controls-free” check, then tried to take off and sadly did not abort.

‘Just Read’

When I was going through USAF pilot training, two of us young student-pilot second lieutenants got an instructor pilot (IP) aside one day. My buddy asked the all-knowing, seven-foot-tall IP-god-like human, “Do you have any advice for us, sir?” Because we really, really wanted to graduate.

“Read,” the IP said.

I asked, “Read what, sir?”

He said, “Just read. There is so much information, just read.”

And he was right. He meant read the flight manuals, etc., but there are so many incident and accident reports out there. He’s more right now than he was back then, because now there is more to read. It’s good to look for the little bits of new information—clues to the cause of the accident—that I can chuck into my bag o’ clues.

Someone wrote on one of these accident-report sites: “Don’t judge—learn.” To whomever wrote that, well-said.

These “clues” are information that I don’t have to personally experience to learn from. I mean, how many accidents can a pilot have in one life, anyhoo? (Turns out there’s no cap, but the limit authorized by the FAA is “one fatal one.”)

Plus, if I listen to someone tell a story about an accident, there often is misinformation being spewed, at twelve gusting twenty, depending on how much coffee the storyteller drank and how big their ego is, which is often a gallon and massive, respectively. Their story is based on what they pilot heard or remembered reading. After 12 retellings, it’s surprising that the accident even involves a pilot and an airplane: “I heard there was this one guy, on the TV show Bonanza….”