The day’s mission was to get me and my Debonair from Wichita, Kansas, to Las Vegas, Nevada, in loose formation with a friend who would be flying his Piper Comanche 180. Although we had scheduled this trip weeks ago, we both presumed the other guy a) had done this before and b) knew how. Over coffee the morning of our planned departure, it quickly became obvious our presumptions were in error. That was the bad news.

The good news is we were flying the same route at the same time at the same altitude, so we could divvy up the planning workload. This was back in the dark ages, before electronic charting, so we spread out a few square meters of low altitude en route paper charts over the kitchen table and eyeballed the route together. The calculators came out, we pored over the Airport/Facility Directory, dialed up DUATS on our laptops for a weather briefing and talked to Flight Service about Notams. Since then, the technology has changed a lot, and we have some new tools as one result. But the basics of familiarizing ourselves with a new route remain pretty much the same. So do the choices.

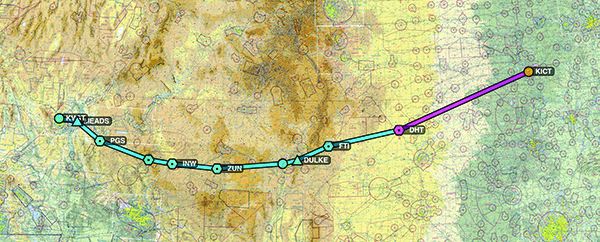

For a flatlander accustomed to parsing shades of green on a sectional, it can come as a rude shock that the cartographers seem to have run out of that color and replaced it with browns. The image at the bottom of the opposite page tells some of the tale about the routing for the trip described in this article’s main text but omits any discussion of minimum en route altitudes (MEAs), much less special-use airspace. In fact, vast swaths of the airspace between ICT and VGT are populated with high MEAs and SUA, both of which make for long legs with little in the way of divert airports.

Even if you’re not planning to fly IFR, it’s a good idea to review the MEAs along your planned route and compare them to other routing choices. Remember that the maximum elevation figures—the large blue numbers in each quadrant of a sectional chart—don’t consider things like navigation, communication or radar/ADS-B coverage.

ROUTING

It was late summer/early fall; the season’s convective activity had died out while winter’s low ceilings and airframe icing hadn’t reached their full potential. Advertised weather was basically clear and a million, with light winds. But it soon became obvious going direct wasn’t going to, umm, fly. The minimum en route altitudes on those airways were too high for comfort. Too, we’d both need/want to make a pit stop en route, so that had to be factored in. We both had supplemental oxygen, but not enough for an extended stay at altitudes where it was required.

Looking at MEAs and divert airports, we chose a southerly route: More or less direct to Albuquerque, N.M.’s Double Eagle II Airport just over the halfway mark for a fuel stop, and then airways over Winslow and Flagstaff, Arizona, followed by a northwesterly jog to get into the Las Vegas area. All in all, it was 908 nm. It would take most of the day and, while we would traverse the highest terrain in daylight, we would be landing in Vegas after sunset. The sidebar at the top of the opposite page has more detail.

Considering our lack of familiarity with this route, it looked like a pretty good Plan A. The thing about getting off the beaten path—at least when flying IFR in the CONUS—is it’s pretty seamless. The charts are consistent and well understood, and ATC is pretty much the same no matter if it’s a Center, Tracon or tower. The biggest trick to this part of the planning actually involved Plan B, not Plan A.

Neither of us had been to Double Eagle II before, but a quick glance at the runway lengths confirmed it would not be a problem for our puny little piston singles. Then we looked at the field elevation, 5837 feet. That was close to a mile higher than Wichita, so we both boned up on high-density altitude operations. The big thing, though, was checking to make sure we had options over the high ground west of Double Eagle if “something” happened.

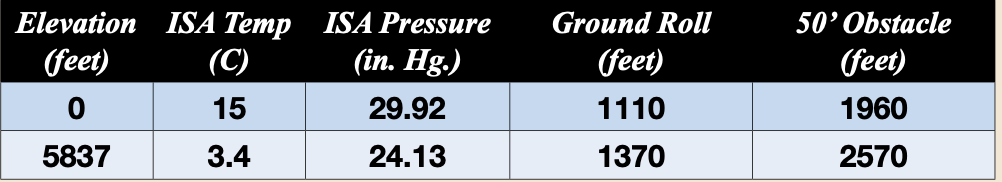

This trip was the first time I had operated at an airport where calculating takeoff performance was pretty much mandatory. On one level, I knew that my gear, full tanks and I didn’t come close to maxing out my Debonair’s gross weight, not to mention the available runway. But it’s always interesting to run the numbers. For this comparison, I chose a sea-level field elevation and standard day, with the airplane at max gross, and then bumped it up to Double Eagle II’s elevation, and what the pressure and temperature would be on a standard day:

The results speak for themselves: A gross-weight Debonair at ISA sea level gets off the runway in just more than 1100 feet, needing almost twice that to get over a 50-foot obstacle. At Double Eagle II, I would need almost 1400 feet to get airborne but almost twice that distance to clear the obstacle.

AIRPORTS

Which brings us to considering the airports along the way and what, if anything, made them special or different from what we’d grown accustomed. Flagstaff and Winslow were pretty solid divert solutions. Both had fuel and long runways, plus other services like hotels and rental cars. Push came to shove, we could park the airplanes and drive the rest of the way. The other good news? At Double Eagle II, we were already halfway back to our cruising altitude, and it wouldn’t take long to get down to Flagstaff or Winslow for a landing in an urgent situation.

Another bit of good news is that area surrounding the airports we used and planned to use in the event of a diversion were relatively free of tall obstructions or terrain. That’s important, thanks to the field elevations involved and our relative lack of proficiency in high-altitude takeoffs and landings. The sidebar at right is a quick snapshot of the performance hit my Debonair would take on a standard day at Double Eagle II versus a sea-level airport. Of course, finding a standard day is rare, and real-world takeoff performance usually is worse, thanks to wear and tear on the airplane and to poor technique.

In the event, we used all the tools available to us to familiarize ourselves with the airports in both Plans A and B. Those tools included VFR and IFR charts, plus approach plates and the airports’ A/FD (now the Chart Supplement) entries. Tools we didn’t have then, but would also look at today, include Google Earth and the various features available on electronic flight bag (EFB) apps like ForeFlight. These include extended centerlines, profile views and synthetic vision, to name a few. Once on the ground, those same EFBs offer additional help to pilots unfamiliar with the facility in the form of georeferenced taxi charts displaying our GPS-derived position and even the ability to mark up the airport layouts with our cleared taxi route once on the ground. The sidebars on this page feature some of these tools. Keep in mind, of course, that even those of us lacking an EFB in the cockpit can get seamless service from ground control at towered airports simply by using the phrase, “Unfamiliar. Request progressive taxi clearance.”

One of the really cool tools we can use when flying into or out of unfamiliar airports is Google Earth. Sure; it gives us a detailed, aerial photograph of the airport, but that’s available in our EFB with the right layer selected. What Google Earth provides in addition is a photo-realistic street-level view that can be adjusted for altitude. At right, the departure end of Runway 03 at Flagstaff, Arizona, is pictured from about 200 feet agl, showing a pine tree orchard straight ahead and a paved road slightly to the left. Pick your poison.

SCENARIO-BASED RISK MANAGEMENT

If we’re doing it right, our planning for flights to and from unfamiliar airports and locations is perhaps the epitome of what has come to be known as scenario-based risk management training. By asking and answering the “What if?” questions on the ground well before encountering them in real time, we’ll already know what to do when the need arises. And perhaps no amount of planning and “what-if’ing” will answer all the questions that may arise. That’s when your training and experience come into play.

Depending on where you go, it’s possible you don’t need much additional flight planning or preparation from what you normally would perform. It used to be we had to do a lot of this on our own, with paper charts and plates, a calculator to figure range and endurance, an online session via dial-up and a phone call or three. These days, a good EFB and web access gives us better information, including the ability to visualize where we’re going and what it will look like when we arrive. There’s no excuse for not being aware of where you are once you get there.

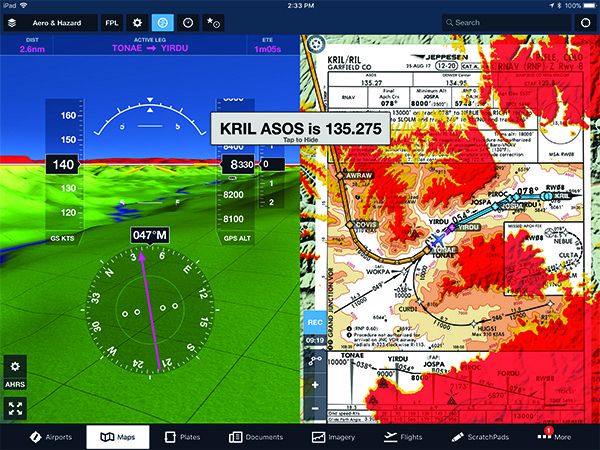

When synthetic vision (SV) first became available in GA cockpits, I was somewhat skeptical. Anything that presents a pretty picture, I thought at the time, will find a market. These days, SV is available on high-end EFB apps and can brings lots of bells and whistles to the cockpit for not much in the way of a cash outlay.

The image at right, courtesy ForeFlight, shows how its EFB app can be configured with its SV presentation in one pane and a Jeppesen approach plate, displaying terrain, our route and even a curved approach path to show us the way home, in the other. As a means to overcome any lack of familiarity with our route, terrain and/or the destination airport, SV can relieve a lot of anxiety and workload. As always, how we process this information and what we do with it is key.

Jeb Burnside is this magazine’s editor-in-chief. He’s an airline transport pilot who owns a Beechcraft Debonair, plus the expensive half of an Aeronca L-16B/7CCM Champ.