Over the years, I’ve cancelled several planned flights, answering the go/no-go question in the negative. Many other flights got rescheduled and were completed—either earlier or later than the original plan—while only a handful were attempted but never completed, at least not in keeping with the original plan. Weather has been the most frequent reason for an outright cancellation with my personal fatigue coming in a close second, followed in distant third place by mechanical reasons. Considering we’re talking about hundreds of takeoffs and thousands of flight hours, that’s not a bad record.

What’s missing from this summary is the number of flights that didn’t proceed as planned, those completed more or less on the same schedule envisioned days before takeoff, but perhaps not at the same altitude, over the same route or even under the same flight rules. And in fact, some flights began not so much with a firm “go” decision to depart and complete the flight, but with a shoulder-shrugging decision to take off and “see how it goes.” In other words, for some flights, a series of go/no-go decisions were made, with some of them decided in the negative. All of which is to argue that there’s usually no single, all-encompassing “go” decision, and even the “no-go” decision can be reversed. In other words, we rarely make a single go/no-go decision, but a series of them. And we usually reevaluate our choices multiple times each flight. How and when we do that is itself a field of study, known as aeronautical decision-making.

The event inspiring this article involves a trip I recently canceled the morning of the planned departure. It would have been a day trip, about 1+45 in each direction, all to spend a few hours on the ground, then turn around and come back. I soloed and earned my private at the destination airport, and having visited it scores of times since, I knew the route and the facilities along the way quite well. The airplane was in top shape, I was rested and relatively undistracted, and there was no real pressure on me to adhere to some schedule.

The weather sucked, however. While my morning departure and evening destination airport was advertising clear and relatively calm conditions throughout the day, the midday destination was going to be down around ILS minimums when I wanted to arrive, and not much better when I wanted to leave. I had a relatively fresh instrument proficiency check under my belt, so I was legal. My familiarity with the airplane, the route, the approaches at the destination and the myriad options for diverting—including having enough fuel aboard to just turn around and fly home—all argued in favor of a “go” decision. But I ended up driving instead, trading less than four hours in the airplane for 10-plus hours in the car, and a past-my-bedtime arrival back home. Why did I scrub the flight? Because I just didn’t want to deal with low IFR that day.

The punchline is that I got a good look at what the actual weather was and how it differed from the forecast: It didn’t. The forecast was spot on, with rain and a couple of miles of visibility under a 300-to-600-foot overcast pretty much all day long. At one point after arriving at my ultimate destination, I heard a piston airplane overhead, sounding for all the world like someone shooting one of the RNAV (GPS) approaches into the nearby airport. I could hear it, but couldn’t see it, and I have no clue if it got in.

A SCENARIO

Framing our decision as a binary, go or stay choice does us a disservice. Instead, we should reframe the question into something completely different, with multiple answers and approval/veto points.

For example, let’s create a scenario involving a 500-nm trip in a Cirrus SR22. The pilot (that’s you) is instrument-rated and current for night and IFR. The airplane is in top shape, and the flight is scheduled for a Monday afternoon departure before you need to be at a business meeting on Tuesday morning. The payload is just you, an overnight bag and your laptop in another bag, so the fuel tanks are full. In normal cruise conditions, your SR22 can cover the distance in about three hours, leaving you enough fuel aboard to fly to the destination, shoot an approach and get a least most of the way back if you need.

It’s summertime, and a cold front is between you and your destination, and it’s forecast to still be an issue at your proposed departure time. As you update your weather at noon on the day of your planned departure, the cold front is moving at a leisurely pace and spawning thunderstorms ahead of it. As is typical in summer, there’s the threat of the storms getting together into lines and clusters later in the day and for the cold front to accelerate. Right now, it’s forecast to move over and beyond your destination airport around sundown, leaving gusty but relatively clear conditions behind. As you check weather radar at noon, the direct route features several splotches of red and yellow, but they appear easy to circumnavigate. After cold-front passage, the weather along the route is forecast to be benign for the next several days.

This scenario presents you with a wide range of choices and decisions. Of course, you can cancel the trip outright, but there doesn’t seem to be any reason to do that right now. If we scrubbed planned flights every time there was a red splotch on the radar, we’d never fly in summer.

Sometimes, the plan can be years ago, as the image at right from an aircraft tracking app depicts. It shows me letting down into Wilmington, N.C., in advance of the squall line I had been keeping off my left wing since leaving Florida.

Although I was headed for the Washington, D.C., area, the weather wasn’t cooperating—the squall line extended from New England south to the Gulf of Mexico. Airborne Nexrad radar wasn’t a thing yet, and at each frequency change, I queried the new controller about holes in the line or routes through it. Every time, I got basically the same response: The only flights getting through to the other side were jets in the flight levels.

Ducking into Wilmington before the squall line arrived was the best decision and, while I could have continued on after it passed, dinner and a good night’s sleep was the better choice. I motored home the next morning in clear air.

TIMING IS EVERYTHING

Another choice is to leave for the airport right now, deal with the cold front and its convective activity before it gets too hot later in the day, and be on the ground at your destination well before it all moves through. That’s actually a good choice, since the worst weather isn’t forecast until after the workday ends. It will, however, be building and will worsen as the day progresses.

Part of “going” with this option is the fairly certain knowledge you’ll be dodging building thunderstorms and dealing with a cold front for at least an hour or so before reaching your destination. If you wait until your planned departure time, you’ll have all that to deal with, anyway, plus the possibility the thunderstorms will be more widespread. Leaving early, by the way, also gives you maximum flexibility to make your meeting if you have to divert for any reason—you can rent a car and drive the rest of the way.

Other options include sticking with Plan A and leaving at the scheduled time, delaying your departure until the cold front passes or calling it quits for the day and planning a before-dawn departure tomorrow to make your meeting. In fact, leaving now affords you the most daylight with which to tackle the thunderstorms. But you decide to stick with Plan A, taking off at 1600 local time, with an expected arrival at 1900, well before sunset.

As part of its risk-management curriculum, the FAA has a couple of models for how pilots make decisions.

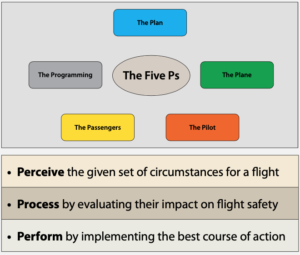

The Five Ps

The FAA’s “Five Ps” stems from the “idea that pilots have essentially five variables” to manage and which, taken together, can force a single critical decision, or several less-critical ones, that can create a critical outcome.

The Three Ps

The Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge also suggests using the Perceive, Process and Perform model to help evaluate “every aeronautical decision that you make.” Although pilots inevitably make mistakes, anything you do to “recognize and minimize potential threats to your safety will make you a better pilot.”

EN ROUTE DECISIONS

Once airborne, you find conditions pretty much as advertised, with widespread cumulus and good visibility, and your Nexrad weather displays an area of storms between you and your destination. For the time being, you continue as planned, monitoring the Nexrad and keeping an ear tuned to the frequency and what other pilots are doing about the weather. You’ve got an hour or so before you reach the worst of it, so you decide to continue. Soon, however, your Nexrad display shows more yellow and red than green, and the radar returns are starting to bunch together, as forecast.

Options include turning around, of course, changing your route to avoid the worst of it or plowing ahead, hoping you’ll find a few holes. Hoping you’ll make it through a hole—just like hoping you have enough fuel, or hoping the icing won’t be too bad—isn’t a plan, but it is poor airmanship, and there’s no need to turn around, yet. So you work out a new route with ATC that will take you around the worst weather. After programming your avionics, the new route adds 15 minutes to your en route time, well within your fuel reserves.

An hour later has you 45 minutes from your destination. You’ve circumnavigated groups of red and yellow Nexrad returns, but you’re staring at a fairly solid splotch of them between you and your overnight. You’d accept scooting between a couple of them in visual conditions so you continue, spending less time looking at Nexrad and more out the windscreen. As you get nearer, though, it’s obvious there’s no clear, visual path through these storms, so you have to decide what’s next. Since they’re closing on your destination, attempting an end run around them may turn into a dead heat. By then, you’ll be down to 1.5 hours of gas, which is getting close to your personal minimum fuel of one hour.

What are the options? You correctly reject the idea of poking into the storms, hoping for the best and riding them out, as the foolish choice it is. And you’re so close to your destination, you don’t have the fuel to return home and try again tomorrow without stopping. It doesn’t take you long to realize your best choice is to land at a nearby airport, refuel and monitor the storms until they’re past your destination. Then you can make the short hop to your destination.

Some decisions aren’t really decisions at all. Instead, as a result of training, experience or fear, we automatically take an action requiring no real consideration. Reacting to an in-flight engine failure might be one example while avoiding building cumulus clouds or icing might be another.

The FAA’s Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (PHAK) phrases it better: “In an emergency situation, a pilot might not survive if he or she rigorously applies analytical models to every decision made as there is not enough time to go through all the options. Under these circumstances he or she should attempt to find the best possible solution to every problem.”

“Experts take the first workable option they can find,” the PHAK continues. “While it may not be the best of all possible choices, it often yields remarkably good results…. This is a reflexive type of decision-making anchored in training and experience and is most often used in times of emergencies when there is no time to practice analytical decision-making.”

DECISIONS, DECISIONS

And that’s what you decide to do. Bringing up the “nearest airport” function on your avionics, you see a nearby county airport with instrument approaches and a courtesy car. It also happens to have cheaper fuel than your destination, so you can actually save some money. You tell ATC of your new plan, are cleared to descend and fly direct to the divert airport, and 30 minutes later you’re on the ground. Three hours later, at dusk and after a smooth, short hop, you land at your destination.

Yes, this is a contrived scenario, and I’ve eliminated everyday complications like schedules and passengers from the equations. Those considerations may be valid ones, but they’re secondary to ensuring the airplane and its occupants get on the ground safely.

There is no single go/no-go decision. There are a series of them, and each one creates a new set of circumstances that factor into the next decision.

Jeb Burnside is this magazine’s editor-in-chief. He’s an airline transport pilot who owns a Beechcraft Debonair, plus the expensive half of an Aeronca 7CCM Champ.