Roper 35, traffic in your twelve o’clock, three miles, type and altitude unknown.” This ATC call got our immediate attention. We were blitzing along in a U.S. Air Force T-38 at 300 knots and about 3000 feet msl, southbound over the Sacramento Valley. The controller might just as well have said, “I hope you’re looking out the windscreen—you have about twelve seconds to hit or miss this guy.”

Clearing the air around us like two terrified pilots would clear—because we were two terrified pilots—we blasted along, bug-eyed, looking everywhere ahead, left and right—and passed a couple hundred feet just about right under a small single-engine airplane. We were close enough to see that the pilot clearly never saw us—he was looking straight ahead, not at us. He made no avoidance move. He may have gotten an ATC call advising him to look out for us. He may not have.

The sky is big—right up until it isn’t.

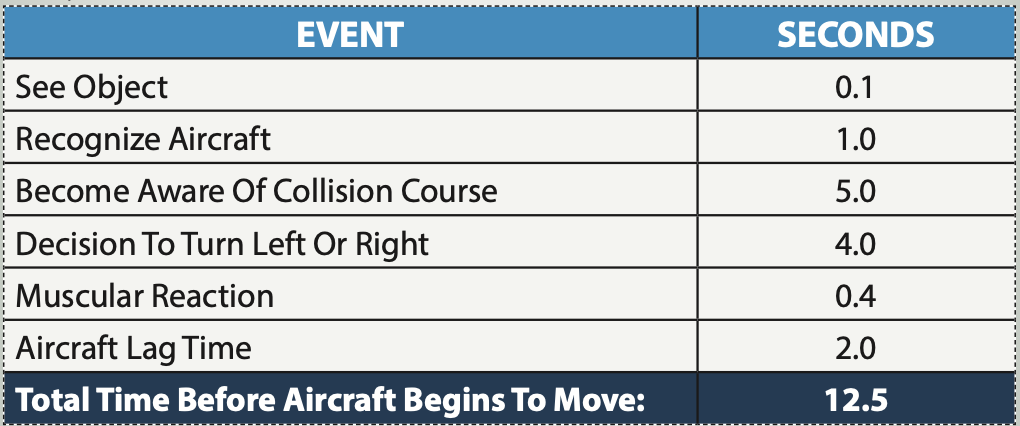

The FAA’s Advisory Circular AC 90-48E, “Pilot’s Role In Collision Avoidance,” is the latest (October 2022) update to the agency’s guidance on how to avoid a mid-air. It’s a comprehensive resource for anyone. In addition to the traffic scanning technique presented by the image at the bottom of this page, it also includes the table below, an Aircraft Identification and Reaction Time Chart, which uses data from Canada’s Transportation Safety Board and the U.S. Naval Aviation Safety Center.

IT’S JUST A JINK TO THE RIGHT

After that near mid-air collision (NMAC), we got very good at keying the mic and quickly and clearly spitting out the phrase: “Roper 35 searching—no joy—request immediate avoidance vector.” And then get ready to probably jink to the right.

What about when there is no airport nearby, and you’re flying VFR, no flight plan, no flight following? Is there any risk of a mid-air? Yes; there’s always that risk.

About 20 nm west-northwest of my old airport, KJYO, the Leesburg (Va.) Executive Airport, there was what we called the “training area.” We CFIs would fly out there with our students in single-engine aircraft—Cessna 172s, mostly—and do maneuvers. “Stalls and falls,” turns about a point, eights on pylons, lazy 8s, simulated engine-out landings, etc. I was a new CFI, and didn’t realize all four flight schools at the airport used the same practice area. But I found out the hard way, when the “big sky” suddenly, uh, wasn’t.

I was flying out of KJYO one fine day, and the tower, which has radar, said to an incoming aircraft, “Be advised there is a Lancair coming your way, 1400 feet, seven miles.” That pilot basically panicked, as we were going “head-to-head,” and his voice came back on the radio, “He’s still coming right at me!”

I could see on my traffic display that he was several miles away, and before I could say or do anything, he turned about 20 degrees left. I said to the tower, “Lancair 12345, climbing, avoidance vector to the right,” and turned right about 30 degrees and, now that I was out from under the Class B shelf that restricted me to 1500 msl or lower, I crammed in full power and climbed. I was well clear, instantly, but thought, “Dude! You turned left?” Well, he was scared and panicked; I get it. If you’ve ever panicked while flying—even for a few seconds—you know what I mean, and if not, words can’t describe it. But turning right instead of left—look up the right-of-way rules—should be the default direction when you have the choice.

The lessons? Stay away from crowded airspace unless you have to be there. And be ready for someone to do the wrong thing, be in the wrong place, make the wrong move.

A SURVIVABLE MIDAIR

In Texas, near San Antonio, a pair of young USAF T-38 instructor pilots from my base had a “no-kidding” mid-air collision—no NMAC for these guys. They sheared the entire front end off a Cessna 172, striking it a 90-degree angle with the vertical stabilizer of the T-38. It cut off the front end of the Cessna at the firewall. You’d think this is a sad tale, but wait.

The 172 could glide—and did. But the shock was so great—physically, mentally—to the Cessna 172 pilots that the CFI aboard, along with a young French student pilot doing instrument training with a vision-restricting device, tried to start the missing engine seven times on the way down. That’s what panic can do to the mind. But the CFI snapped out of his panic—he just couldn’t get that engine started, since it was lying in a field in a pile—and glided the beat-up, no-front-end Cessna 172 to a safe landing on a road.

The T-38 that hit the Cessna was going 300 knots, and spun and tumbled out of control. We T-38 pilots were lectured, over and over (and over): “To avoid spinal injury when ejecting, sit up straight, back against the seat. Otherwise you are certain to suffer spinal compression injuries.” As luck would have it, one of the T-38 pilots was pinned up against the side of the cockpit, due to transverse Gs, and couldn’t sit up straight. Forced by Gs to bend over and sideways in the out-of-control aircraft, he could only pull up on one of the two ejection handles. He told us later he thought to himself, “This is gonna hurt!”

Boom! He ejected and floated down safely, unhurt, as did his partner, the T-38 crashing in a fireball somewhere in the Texas desert.

(Later, TV news interviewed the young French student pilot. He was asked what he thought. He said, in French-accented English, “I was not afraid.” A joke soon went around the T-38 community like wildfire: “TV interviewer to the French student: “What were you thinking after the midair collision?” French student: “Four more, and I’m an ace!” Pilots—we love our black humor. Non-pilots don’t get it, which is precisely why we don’t tell pilot jokes in public. In fact, it’s a violation of some FAR, I believe.)

In its accident report, the NTSB said the cause was, “Inadequate visual lookout by both pilots in the T-38 and by the instructor pilot (CFI) in the Cessna 172.” Duh.

How can I maneuver to deconflict, miss someone who might get too close? Here’s one way.

I was about seven-eight miles out, flying toward KJYO, Leesburg Executive Airport, and off to my right about four miles away I saw a King Air, slightly faster than me, also angling toward the airport. He was accelerating—it looked like he was racing me to the 45-to-downwind entry point.

We were on converging semi-parallel flight paths, and we were going to meet somewhere just before entering the 45-degree entry leg. I made a quick decision, and a 45-degree hard-banked turn directly at him. Briefly.

Then I rolled out and flew straight ahead. Of course, he continued to fly straight and level and zoomed by. I rolled back left into a turn toward the airport, a mile or so behind him.

I learned this from flying T-38s in tactical formation in the Air Force. Someone alongside me going the same direction, some (safe) distance away? To get behind them, turn 90 degrees right at them, roll in behind. I’m flying a longer groundtrack than them, and they’ll spit right out ahead of me. Same idea as an “S” turn, really— a longer groundtrack.

Later, on the ground, the guy said he was purposefully racing me to the airport—ha ha, ha, he chuckled—and was surprised when I turned right at him. He wondered what I was doing. I explained how I wanted to get behind him and keep him in sight out the front windscreen. He didn’t get it, but not everyone flew tactical formation in supersonic jets, and would think of “turning into” someone. You have an airplane. You can maneuver.

THE FAILURE TO CLEAR

Failure to see-and-avoid is the number-one cause of midair collisions, perhaps in part because that’s the primary collision-avoidance scheme pilots have come to accept. It depends on efficient use of visual techniques and knowledge of the eye’s limitations. So what affects our eyes, and what limits our ability to see?

Obstacles in the cockpit. Blind spots. There’s a saying for that: Keep your head on a swivel. Atmospheric conditions—forest-fire smoke, haze, even clouds: It can be hard to see a white aircraft against a white background.

Ground clutter and background color: Sometimes I have really strained to see an aircraft on final or short final, finally sighting it over the runway. Glare also can be blinding, along with white light at night in the cockpit killing night vision. Windshield deterioration and distortion, especially dirt and bugs. Even the airplane’s wing is an obstacle and it doesn’t matter if it’s a high-wing or low-wing—both block vision in one direction, especially in turns. Last but not least, the oxygen supply in our blood, especially at night.

It also takes some time to change our focus from inside the cockpit to outside. Add in the reaction time detailed in the sidebar on page 21, and it’s plain that even if we’re looking, we might not be seeing.

CHECK SIX

Once when I was a copilot, flying the T-38 at Beale Air Force Base, my instructor, SR-71 jock Major Brian Shul (Google him) said, “Lt. Johnson, I want to see that helmet faceplate facing the direction of your turn.” In other words, he could see my large, dark visor sticking up in the front cockpit, and he could see whether or not I was looking up and left, for example.

This was good advice then, and it is today. I turn my head and look where I’m going, especially in the pattern, even if the tower says to go ahead and do whatever.

In Fargo, N.D. (my hometown) recently, a man was sitting stationary in a Jeep in the left-hand turn lane, with his blinker on, when a big yellow school bus rear-ended him going about 25 mph. Maybe if the Jeep driver had been checking his mirror, he would have seen that big yellow death machine bearing down on him and gotten out of the way. Maybe. Anything is better than not clearing, not “checking six.”

You mean I have to clear behind me while flying? Yes. Eighty-two percent of mid-air collisions involve an aircraft overtaking another one from the rear, according to the AOPA Air Safety Foundation. The lesson, for me, at least: I may be “in the right,” but I can be “dead right” if I don’t clear. Someone may indeed be on the wrong freq, in the wrong place at the wrong time (and isn’t that the definition of a mid-air?) or make no calls.

Here are some mid-air avoidance tips from AOPA, highlighting procedures at non-towered airports.

• If you are working with approach control prior to reaching the airport, monitor CTAF on your second radio or a handheld.

• Report your position 10 miles out and listen for reports from other inbound traffic. Report entering downwind, turning downwind to base, and base to final.

• If you are unsure about the location of another aircraft on the frequency, ask.

• Remember there may be aircraft in the pattern without radios—or not making calls.

• Slow down. Slower speeds allow more reaction time.

• Check behind and below you at least once on final.

• Report your position outbound, and be aware that most pilots omit position reports after departure.

• If conducting an instrument approach or straight-in, report distance in miles rather than navigation fixes or ground reference points.

LISTEN LOTS, TALK LITTLE

Since most mid-airs occur at non-towered airports in day VFR, what else can I do to clear the airspace around me and minimize the chance of a mid-air? I gotta listen to the radio, of course, which provides clues on aircraft behind me, out of sight or hard to see. I should tune and verify the local frequencies well before I enter the airport traffic area, about 10 miles out.

I should identify the airport name at the beginning and end of all my radio calls. I hear calls like this, often: “Detroit Lakes traffic, Cessna 254ZY, left base, runway one-four.” Pilots (like me, often) leave off the last, most helpful part, “Detroit Lakes,” or whatever airport it is. I sometimes hear abbreviated calls, but they’re still quite informative, like I heard recently at Hampton Roads Executive Airport, KPVG: “Hamp Roads traffic, Cessna 12345, right base, runway one zero, Hamp Roads.”

Since many airports share the same CTAF, a call from a pilot, say, 50 miles away can scare years off your life when they don’t include the location airport at the beginning and end.

Ya gotta squeeze in quick radio calls if the radios get busy on a good-weather day. And don’t use the published fix’s name when shooting approaches, VFR or IFR: Give us your position and distance from the airport, not “the high school” or “the power plant.”

THE BOTTOM LINE

We can’t get complacent about the danger of a possible mid-air or a near-mid-air. Look out the windows. Keep your head on a swivel. Clear like your life depends on it.

Matt Johnson is a former U.S. Air Force T-38 instructor pilot and KC-135Q copilot. He’s now a Minnesota-based flight instructor.