My passenger arrived late, as usual, and talking on his cellphone, as usual. “What about sushi tonight?” I heard him say. Then: “I should be home in 45 minutes.” I tried to attract his attention but he waved me off, as usual. I was surprised that he could be heard over the noise of the hot wind slashing across the ramp.

Finally, he put the phone away and looked at me. “All set?” he asked. This was more of a statement than a question. It’s the kind of moment pilots dread, whether charter, corporate or flying friends to a golf tournament.

“We can’t go,” I said, pointing to the wind sock whipping around enough to hurt somebody who got too close.

“WHAT?”

This was not technically a one-way airport. Runway 22 is uphill and aimed at high terrain. Runway 4 is downhill. Normally airplanes land on Runway 22 and depart from Runway 4. Airport elevation is well over a mile, so density altitude was effectively infinite. The tailwind on Runway 4 was well over the aircraft’s tailwind limitation. So why not take Runway 22, into the wind? For one thing it’s uphill, but on that day there also was some construction just past the end of the runway with cranes swinging back and forth right through the air we’d be flying through if an engine failed.

I explained all this and sat down out of the wind. The passenger started to get a little insistent, so I pantomimed holding up some keys and told him that he could try it if he wanted, but I would not. He calmed down.

Eventually the wind calmed down, too, and we had an uneventful though bumpy flight home. I think he was even on time for sushi.

IN OR OUT?

At one-way airports, airplanes always land one way and take off the other. There are exceptions, of course, but looking into the exceptions might just mean that you are trying too hard.

Let’s focus on two popular one-way airports: Aspen, Colorado (KASE) and Sun Valley, Idaho (KSUN). These are examples; the mountain west has many airports that, while not strictly one-way, present pilots with many of the same challenges.

By the way, during the busy ski season the FAA traffic management system will impose slot restrictions and expected departure times. That’s a subject for another article.

So, let’s get ready….

GET READY!

Getting ready absolutely necessary. These are airports with a lot of difficulties, and you have to have a plan. The plan might change, but being ready for that is part of the plan. All of which sounds a lot like FAR 91.103, Preflight Action, which begins, “Each pilot in command shall, before beginning a flight, become familiar with all available information concerning that flight.” The difference is that there is much more information for these airports. What kind of information is there?

A one-way airport, whether a busy terminal for regional airliners or a rough-and-tumble backcountry strip, is a one-way airport because of terrain. Why do people build airports in high terrain? Many serve ski resorts. The mountains are their natural home. But, high terrain also breeds lots of thunderstorms, which require three ingredients: moisture, unstable air and a source of lift. In this case, the source is called orographic lift, caused when an air mass runs into a mountain. That forces the air to rise. It’s the source of ridge lift for gliders.

One would think that high terrain makes these airports suitable only for turbine-powered airplanes or very high-performance piston airplanes. Approach controllers assign altitudes like 14,000 during approach segments. But, at least one of these airports has a flight school using a normally aspirated Cessna 182. They have to fly to a valley for IFR practice, because the missed approach procedure needs a steep climb to 10,500 feet msl.

What other problems can these airports have?

As a rule, skiers, hikers and mountain bikers don’t like airplane noise. That means there are noise abatement procedures. Some are designed to stretch your comfort level about flying close to terrain. Some keep you high on final.

Ski resorts mean snow. Snow means plows; too many operations on snow-covered runways lead to bent metal. But nobody can land with a plow on the runway. An operating control tower can coordinate, but if the tower is closed, pilots and plows have to coordinate between themselves. That’s why more than one of these airports has the warning that aircraft arriving after the tower is closed are “reqd to annc CTAF [sic] when they are on [sic] 20, 15, 10 and 5 mis out and shrt final. Eqpt may be on rnwy.”

Where is all this information? It’s in the Chart Supplement (formerly the Airport/Facility Directory, A/FD). You must read the Chart Supplement before going to this kind of airport; the approach plates are not enough. (By the way, how come changing the title didn’t eliminate the abbreviations?)

ASPEN

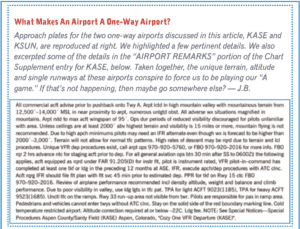

Every pilot from my generation is familiar with Aspen because of its unusual missed approach procedure. It was on the instrument rating knowledge test (or whatever they called it back then), and the examiner asked about it on my CFII oral exam. The procedure was to fly outbound on a localizer back course, which meant normal needle sensing. This was important in the days before effective moving maps.

The Aspen airport is in a narrow valley, squeezed between a highway and the mountains. It has instrument approaches, but they are all “NA at night.” Visual approaches to Runway 33 fly down the right side of the valley, very close to the terrain. If you’re not close enough, the tower will tell you to get closer! Departures from Runway 15 make an immediate right turn toward the mountains.

Because it’s a one-way airport, expect departure delays. Some days, I swear, the traffic density matches Chicago O’Hare, with airplanes flying their downwind legs 20 miles or more from the field. The approach controllers are really good at what they do, but they may have 10 airplanes on the approach. That impacts your fueling decisions. While it’s tempting to take on as little fuel as possible because of the high density altitude, that needs to include 20 minutes or so of idle fuel while you wait. And, in the thin air, you need to watch engine temperatures carefully while sitting still.

Airports in the mountainous parts of the world have backcountry strips that offer amazing access to the local beauty: fishing, hunting, hiking and other activities. Most of them are one-way strips in narrow valleys. Few have control towers. Some have no regular maintenance and close when the snow starts to fall, reopening in the spring.

I’ve been to some of these strips, mostly in Idaho, and I overflew several during my one flight in Chile years ago. They’re in the Alps and Appalachians, too.

It’s been quite a while since I’ve flown to these strips and I do not consider myself proficient. I can fly final at the right speed and come pretty close to touching down on my aim point, but techniques for these strips include advice like “pass the twin aspens at 5700 feet msl.” That was the technique 20 years ago, but those trees have grown. Was this the airport with the cliff face on the left side of final or the right?

Hire a guide if you want to go. That’s what I would do.

SUN VALLEY

Sun Valley, Idaho, was one of the first European-style ski resorts in the U.S., developed by the Union Pacific Railroad. It’s at the top of the narrow valley formed by the Little Wood River. The tower call sign is Hailey, not Sun Valley.

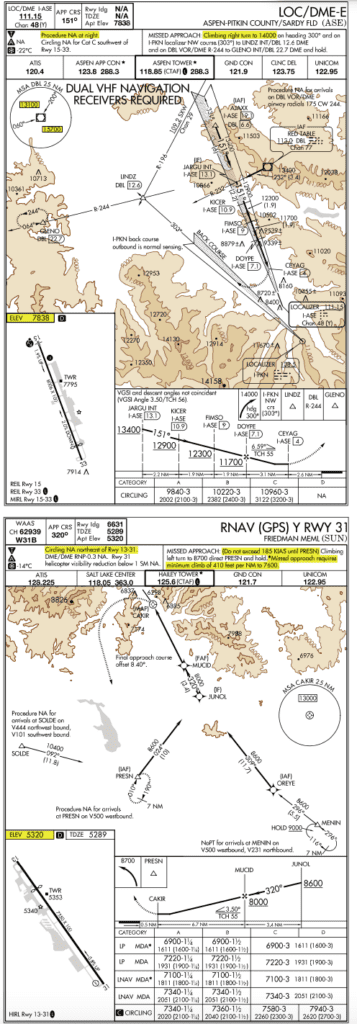

As I write this—again, you must check the Chart Supplement for current data before going there—Sun Valley’s runways are 31 and 13. The runway has an 0.8% grade to the northwest, which is quite substantial. As a rule, pilots land uphill on Runway 31 and depart downhill on Runway 13. Field elevation is 5320 feet msl.

Winds tend to come down the valley, which can be a problem when departing Runway 13. Check your POH or AFM, but very few airplanes can legally depart with more than 10 knots of tailwind. There is a departure procedure to the northwest: uphill, toward terrain and with a complicated noise abatement procedure. In the 30 years I’ve been using this airport, I’ve departed that way once.

Hailey’s approach to night operations is a little different than Aspen’s. The IFR procedures are authorized at night, but that doesn’t make it San Francisco International, either. The Chart Supplement says, “Not recommended for ngt use or in marginal wx by unfamiliar pilots due to mountainous terrain.” It’s another case of disagreement between “safe” and “legal.”

ACCEPT THE CHALLENGE

Pilots who go to these airports reap great rewards, but have to be aware of the hazards. I’ve flown to Sun Valley in a 65-hp Taylorcraft, so it’s possible. King Airs and Citations are a lot easier.

The rewards come from the beautiful scenery and the resort amenities. I hear the sushi in Sun Valley is really good, too.

Jim Wolper is an airline transport pilot and retired mathematics professor. He’s also a CFI with single-engine, multi-engine, instrument and glider ratings.