I had friend—a mentor, really. He flew Hawker Hurricanes in WWII, and had great war stories. Like the time he was jumped and shot down by three Messerschmitts in the North African desert. He described the German machine gun rounds hitting his wings looking “like a sewing-machine stitching.” Looking over his shoulder, he saw the “white puffs of the cannon smoke,” because they switch to cannons when close-in; dead-sticking the Hurricane into the sand and hiding with Bedouins for three days, dressing like them. Or crashing and cartwheeling on the Anzio beachhead because one main landing gear wouldn’t extend.

These stories enthralled me—they still do—and are one reason I signed up for the U.S. Air Force. I didn’t even know where Anzio was. I still don’t.

VEGAS, BABY!

Fast forward a few years. We were in Las Vegas at the Golden Nugget, playing blackjack. My friend—my hero—was dealt two face cards—a 20—and elected to split them and play two hands. “Stupid move,” said the pit boss in an ugly way, which infuriated me. I said, “Leave him alone. He can play any way he wants!”

The pit boss turned on his heel in his silk suit and walked away. I thought bravely, “I will verbally rip your face off, smart guy!”

Later, he came back to our table. I was still seething, ready for another confrontation. I thought, “My friend was a fighter pilot in WWII, flew a Hawker Hurricane against the Germans! He got shot down, even! Don’t tell him what to do!”

The pit boss, in his immaculate silk suit, completely ignored me and said to my friend, “Are you gentlemen staying at our hotel?” My friend said, “No, just gambling.” The pit boss said, “Are you parked in our parking garage?” My friend said, “Yes, we are.” The pit boss asked for our parking ticket, went over to a little stamping machine, and bam, bam, bam, bam, bam, stamped it five times, and then came back with five hours of free parking on the ticket. He said, “Enjoy your time at our hotel, gentlemen,” and walked away.

I turned to my friend, and whispered, “What the heck was that all about?” He said, “Always allow a man to redeem himself, Matt.” I never forgot that, because it was so shocking. The pit boss knew he was rude, and made up for it with the free parking. In response, my friend did the only reasonable thing: accept his attempt at redemption.

LOTS OF SMASH

Fast forward a few more years. As a T-38 instructor pilot trainee, I was re-qualifying in formation flying. I was doing a “turning rejoin,” where the lead goes into a 30-degree bank at 300 knots, gives you a wing-rock and waits in the banked turn. The technique is to fly faster than 300 knots, so as to catch lead. This overtake airspeed differential is called “smash.”

Instructors say, “Get 50 knots of smash, and fly right in on a line to the wing,” etc. Then you fly toward lead and park off their wing, three feet away, in the 30-degree bank. Or an IP might say, “You were carrying a ton of smash there, too much,” etc. Well, you can have a lot more than 50 knots of smash, if you want. There is no speed limit. You can carry 150 knots of smash, or 100, so as to rejoin quicker. But if you misjudge it, and are indeed going to “smash” for real, you do an “overshoot.” This is done by simply ducking under lead and coming up on the other side. It’s the normal way to overshoot—it’s all planned out and agreed-upon, briefed-up.

But I was a rusty T-38 pilot.

So Mr. Rusty came in toward lead with about 100 knots of smash, going about 400 knots give or take 50, and suddenly realized we were gaining on lead way too quickly. I ripped the throttles to idle, banked away from lead and descended.

Oops. Now I’m about 1000 feet below lead, who is waiting in his nice 30-degree banked turn at 300 knots, and—bonus—I’m slow, too, starting to fall behind. I was “down in the hole,” they called it.

The instructor’s voice came over the intercom: “How does this look?” I said, “Not good! Terrible!” beating up on myself before he could. He said in a calm voice, “Well, that’s why we’re out here practicing.” That was magic. No yelling, no criticizing.

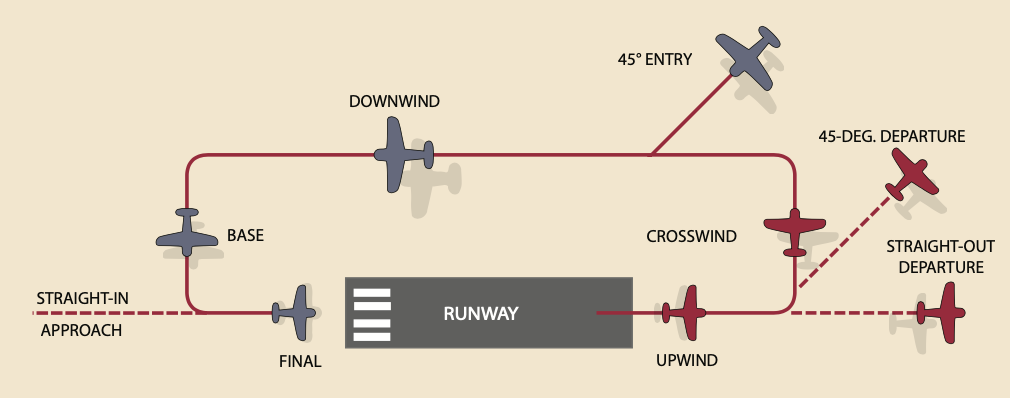

The FAA Advisory Circular Non-Towered Airport Flight Operations (AC 90-66B) includes a wealth of official guidance on how to operate at non-towered airports and fit your aircraft into the flow of dissimilar types. Among its highlights is this reminder: “The FAA does not regulate traffic pattern entry, only traffic pattern flow.” The AC goes on to note, “A visual flight rules (VFR) aircraft on a long, straight-in approach for landing never enters the traffic pattern unless performing a go-around or touch and go after landing,” something other pilots may not fully grasp. But for our purposes of redemption and defusing any sort of conflict, this passage sums it up:

Do not correct other pilots on frequency (unless it is safety critical), particularly if you are aware you are correcting a student pilot. If you disagree with what another pilot is doing, operate your aircraft safely, communicate as necessary, clarify their intentions and, if you feel you must discuss operations with another pilot, wait until you are on the ground to have that discussion. Keep in mind that while you are communicating, you may block transmissions from other aircraft that may be departing or landing in the opposite direction to your aircraft due to IFR operations, noise abatement, obstacle avoidance, or runway length requirements. An aircraft might be using a runway different from the one favoring the prevailing winds. In this case, one option is to simply point out the current winds to the other pilots and indicate which runway you plan on using because of the current meteorological conditions. — J.B.

SO THERE I WAS…

Fast forward a few more years. I’m flying into a non-towered airport at Winchester, Virginia (KOKV). Often, this airport is out of control. Solo students, CFIs with students, older pilots, rusty pilots, pilots not making radio calls, some jets, some helicopters, some military and the occasional sheriff making high-speed car trips down the runway. Guys taking off with no radio call. A “goat rope” is what we called this kind of pattern in the Air Force.

A CFI buddy and I were flying across the runway perpendicularly at 2200 feet msl, 500 feet above the pattern altitude of 1700 feet, just like you’re supposed to do to enter the pattern. I made a courtesy radio call reporting over the field at 2200, westbound for a downwind entry to Runway 32.

We were going to do a right curling turn onto the 45-to-downwind leg. I caught movement, 10 o’clock high. Huh? Yup, there was an aircraft, descending out of about 4000 feet msl and pointed right at where I was going. We were on a collision course, but I had plenty of time, so I yanked my Lancair IV-P, the poor-man’s fighter jet, to the right, jammed in the power and was clear. I did a normal 270-degree turn to enter the Runway 32 downwind, making all the radio calls, and landed.

We taxied over to the fuel pump, and, while I was refueling the aircraft, I noticed two guys park, get out of a Cirrus and start walking to the FBO. Then they turned, and walked toward us. I said to my young pilot-buddy, all of 25 years old, “Hey, come here a sec,” and when he was close I said in a low voice, “Let me do the talking, don’t say anything. I think those are the guys who we went head-to-head with on downwind.”

Like so much else in aviation, successful defensive flying at non-towered airports can depend on situational awareness and, in this case, visualizing your position relative to others. Some tips on establishing and maintaining situational awareness as part of your defensive flying arsenal include:

- Use the radio, sure, but spend more time listening than transmitting. You’ll learn more that way and won’t be stepping on other nearby pilots. Among other things, over-reliance on listening to your own voice doesn’t help you look for traffic, which may not even have a radio.

- Position reports can use familiar landmarks but are of little use to transient pilots. Use distance/azimuth from the airport to report your position, and maybe throw in the landmark, too.

- Exercise extreme caution when at critical points in the traffic pattern, like downwind entry and turning base-to-final. Don’t forget to scan ahead of you on base, either, for the guy who doesn’t know left from right

- It’s okay to identify the inexperienced pilot in the pattern and plan accordingly, but it’s not okay to presume everyone will do the correct thing. If you can’t figure out who is the less-experienced pilot in the pattern, maybe it’s you. — J.B.

‘YANKED AND BANKED’

The two gentlemen looked like they were older, in their 60s, unlike the spring chicken that I was at age 59. One of them asked me some questions about my airplane, while my friend silently fumed and seethed, not saying anything because I told him not to. The other guy was silent.

Finally, I said, “I was at 2200 feet going over the runway and spotted you guys up in my 10 o’clock.” One of the guys said, “Yeah, we were at 4200, maneuvering for the pattern.” I said, “Yeah, it kinda looked like we were gonna be close, so I yanked and banked away.”

The two other guys were silent; my buddy and the other guy. I could see by the look on their faces they wanted to say something, but it would have been kinda ugly—my buddy angry, the other man defensive-looking. The guy probably had a story all prepared about why they were flying where they were. (I know my buddy had a story prepared.) Whatever their story was would have been creative fiction.

We chatted a bit more, the one man and I talking about my airplane, the other two guys silent. I said, “By the way, there is a full-size American bald eagle painted on the underside of my airplane—you can only see it from the underside.” The man chuckled—with a sheepish grin on his face—and said, “Yeah, we saw that. We never would have seen that if we’d been where we should have been.” I laughed, too, and I knew he knew.

REDEMPTION

Those guys knew they had screwed up, big-time, but what would be gained by me confronting them, scolding them? So when he said he saw my paint job, basically because he was in the wrong place at the wrong time, what more could I want? To tell the FAA on them? To yell at them? To say, “I knew I was right and you were wrong! That was dangerous!” I’d already achieved my goal of getting the guys to realize they were in the wrong, and that what they did was dangerous, etc.

The gentlemen walked away, and I told my friend the story of my fighter-pilot friend at the blackjack table in Vegas, and how we should “always allow a man to redeem himself.” He didn’t really buy it. Oh well. Have I always followed my own advice? No, but it’s a goal to shoot for.

MORAL OF THE STORY

I tried to teach like that in the T-38, and later in other aircraft—let the student make the mistake, let the student realize what they did and correct it on the next try. True, sometimes I had to jump on the controls to save us (thank you, afterburners, or immediate-thrust piston engines) when I let a situation go a little too far. But the concept, I believe, is better than a highly critical, negative, detailed dressing-down of a person.

Many pilots are Type A individuals, I suspect: aggressive, determined and fiercely independent. That’s normal—flying takes skill and training. Some surgeons are like this, too, at least on TV and in the movies. So pilots sometimes get emotional on the frequency and in the traffic pattern at non-towered airports (towered ones, too, but ATC provides parental supervision there).

The last place I want to be when angry at someone or something is in a cockpit. If confrontation is what I really want, at least wait until the aircraft is on the ground in the chocks. Even then, a positive change in the errant pilot’s behavior is much more likely if I skip the drama of assigning blame or displaying anger. It very much helps to ask myself, “What’s my motive here, getting a result or looking superior?” It’s especially important to keep my cool when I know I’m right. Which it turns out ain’t all the time, either.

Matt Johnson is former U.S. Air Force T-38 instructor pilot and KC-135Q copilot. He’s now a Minnesota-based flight instructor.