Many pilots lust after hanging one of those magazine-cover-quality air-to-air shots of their airplane on the wall. Speaking as a pilot lucky enough to spend part of my life working my cameras to create some of those photos, you should think long and hard before forming up on another airplane. What you dont know can easily kill you.

With some solid planning and execution, one of those great photos could soon be hanging on your wall. But, even armed with solid preparation, flying formation for photos presents some significant risks, even if you have some well-founded formation flying experience.

A Little History

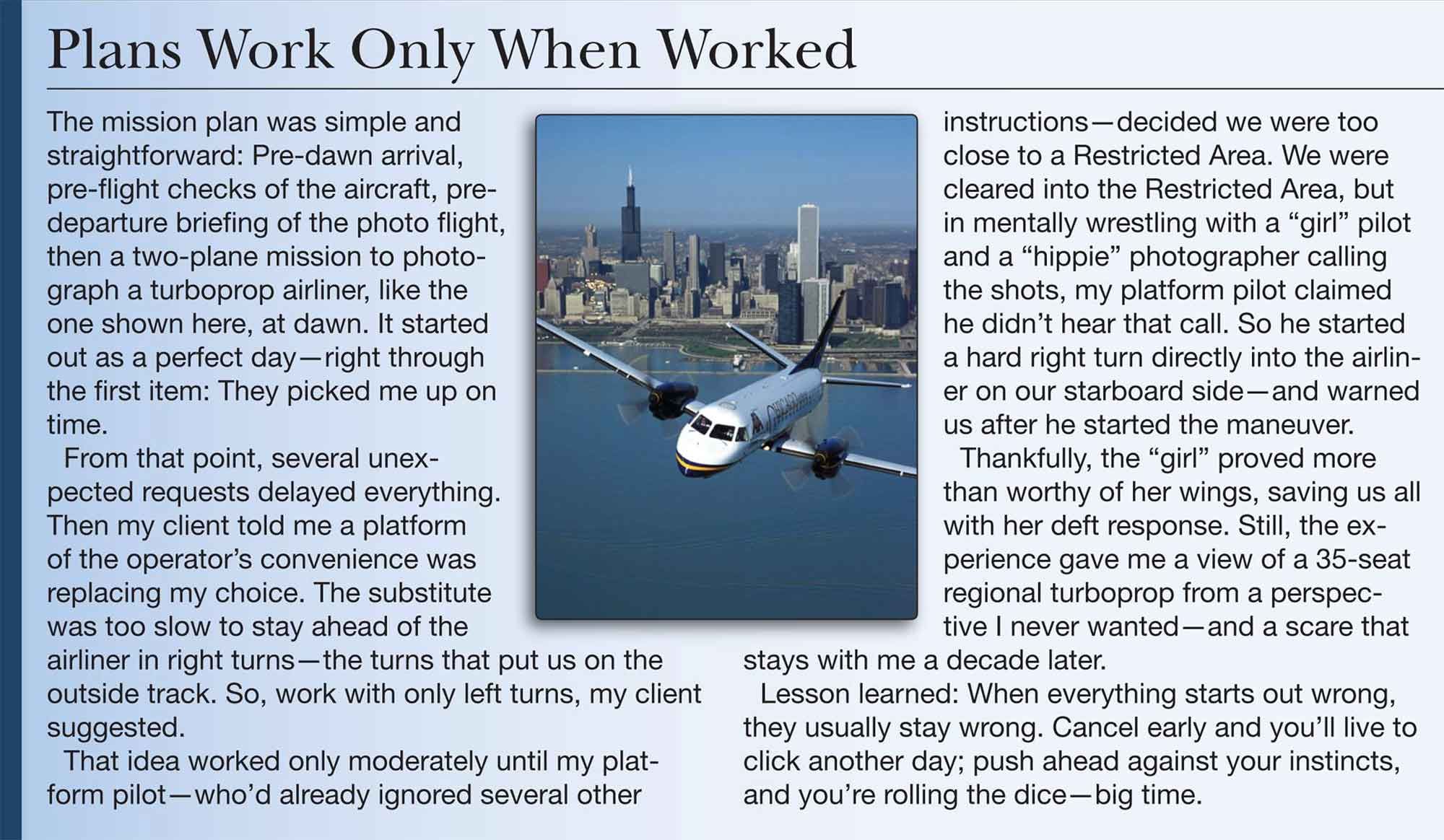

One needs only to look at the February 5, 2006, accident involving two Shorts 360s for evidence. In this accident, two professional flight crews flying turboprop airliners decided to get some post-maintenance photos and video of their airplanes. The fatally damaged aircraft turned right-toward the second airplane-and attempted to pass it. But the first aircraft actually maneuvered into the other, with the resulting collision sending the first plane to a crash, killing both crewmembers. The crew of the surviving aircraft somehow managed to overcome severe damage, make an emergency landing and tell their tale to the NTSB.

The outcome wasnt as positive for four people in two airplanes who launched a photo mission from the Wittman Regional Airport at Oshkosh, Wis., on March 15, 1997. On that mission, the veteran pilot of a Beech A36 Bonanza maneuvered over the top of and through the prop wash of the subject airplane, a Douglas DC-3 converted to turbine power. The DC-3s wake put the Bonanza into the aft fuselage of the big twin, rendering both aircraft uncontrollable. The two airplanes crashed inverted and a little more than a mile apart, killing both pilots in the DC-3, and the pilot and photographer in the Bonanza. These were professionals flying both aircraft; the Bonanza pilot had flown photo platforms before. It didnt have to be that way.

In both accidents, these crews failed to adhere to the basic rules of formation and aerial-photo flying: For one, never maneuver directly over or under another aircraft in close formation.

In reality, formation flying-particularly for photo purposes-is best left to seasoned practitioners, behind both yokes as well as the camera. Shooting photos air-to-air requires skill and preparation, plus a little bit of paranoia. So, unless youre prepared to invest the time and concentration necessary to do this right, I have simple advice: Dont.

But, knowing someone will venture forth in an attempt to get that magic shot, Ill offer up some insights based on a few dozen aerial shoots-both the flawless ones as well as those I nearly didnt survive.

See And Avoid For Keeps

Formation flying of any form is one of those areas addressed by federal regulation. At Sec. 91.111(b), Operating near other aircraft, the FARs merely require that, No person may operate an aircraft in formation flight except by arrangement with the pilot in command of each aircraft in the formation. Thats pretty much it as far as the legalities go, though you may want to check your insurance policy for any exclusions.

So, now were down to how to execute our formation flight. In my mind, its always been the ultimate test of see and avoid-get as close as you are comfortable getting while avoiding contact…or even the fright of contact narrowly avoided.

Safely executing a formation flight for aerial photos works best when you check your ego at the cockpit and use formation-qualified pilots. By that I mean pilots formally trained and recognized as qualified by some organization.

For example, check around your nearest Commemorative Air Force wing or a chapter of the International Aerobatic Club and youll likely find a couple of aviators willing to help out. If they’re really good, they can fly the mission from the right seat and leave the left seat for you to occupy.

Experienced formation pilots know the drill. They won’t launch without first holding a briefing to discuss the mission, its intent and goals. This pre-flight briefing is what usually differentiates a frustrating failure from a safe, productive photo flight and is the opportunity for everyone to get on the same page.

Know What’s Coming

In the pre-flight briefing, there are a number of items you need to cover.The sidebar on the previous page distills them down to some bullet points.Here is the expanded version.

Discuss the flight plan: Where are you going to fly? How high? Is there any restricted or special-use airspace with which to concern yourselves? If so, what facility is responsible and whats the contact frequency?

Equipment: Be sure both aircraft have functioning radios and confirm the frequencies youll use. The air-to-air frequencies can be congested, so crews often will rely on 123.45 MHz for communications.

Also, both aircraft should have working intercom systems and headsets for all participants. We all know how loud it can be in a piston airplane; imagine the sound level with a door removed or a window open. The photog needs to talk to the platform pilot, since the platform will fly lead most of the time. The beauty plane crew also needs to talk, just in case a bogie pops up out of nowhere.

Coordinate airspeeds: Photo missions work best when both planes share a speed range. If the chase plane has to depart much from standard speeds, too many things can go wrong; ditto for the beauty airplane (See the sidebar on the opposite page for a story of how things can go really wrong). With a reasonable speed match, both planes can comfortably maneuver in either direction-left or right-without concern or extra effort.

Discuss turns and climbs: The most-interesting angles for aerial photos come when the airplanes are maneuvering, so we often fly a series of 360-degreee turns, or 180s that reverse direction back for another 180.

Establish a signal for starting and stopping maneuvers: Photo shoots work best and safest when both aircraft start and end maneuvers together.

When its me behind the camera, its my habit to establish some goals and limits-limits as in I wont ask for anything I as a pilot know holds extra risks. I also want the pilots to know what I will request.

When All Else Fails … Scatter

Now that we’ve discussed some air-to-air basics and how to address them in the pre-flight briefing, its time to reflect on the most important part of the briefing and the single most important rule of formation flying: the lost-contact rule.

Everyone must know what everyone else will do if visual contact is lost: Perform the break procedure. Remember: youre working with at least three sets of eyes up there-the platform pilots, the beauty-plane pilots and the photographers. One of those sets of eyes must have an airplane in sight at all times-no exceptions. The instant no one can see anybody else, everyone must break off and head in a different, predetermined direction. If the beauty plane pilot loses visual contact, its time to execute the break. No exceptions. Violate this rule and nobody will ever see the collision coming.

Also remember that the photographer is the one in the chase plane who can see the other airplane when in formation. The platform pilot needs to watch where the planes are going because the photographer is watching the beauty airplane-and the beauty airplane pilot is watching the photographer.

So heres another useful tip: haul observer pilots, if possible. The extra eyes increase your safety margins. Why settle for three sets of eyes when you can have five? And even with five, the potential exists for everyone to lose visual contact.

Hows that happen? Well, sometimes I’ll ask for a tight turn shooting a low-wing airplane from a high-wing airplane; in my quest to get the right angle, the platform plane can slip up so the pilots eyes are below the glareshield-and, bingo, he can no longer see me. At the same time, the beauty plane may rise to the point where I can no longer see it.

As a rule of thumb, my break procedure calls for the platform plane to turn 90 degrees away from the beauty plane while the beauty plane turns 90 degrees in the opposite direction. And the high plane should climb as the low plane descends. By the time we complete this maneuvering, were likely separated by 1000 feet vertically and a couple of miles horizontally. Better too far for a good shot-than too close for survival.

Even with all of the foregoing cautions, instructions and caveats, I would strongly encourage anyone trying to get that perfect air-to-air shot of their pride and joy to find a professional pilot and photographer who has done this before. And please think about what it takes to get that perfect photo next time you decide it would be great to do some formation flying.