Altitude means different things to different pilots. In crop dusting or banner towing, it’s not something we need. When striving for efficiency and economy over a distance, it can be, since the air is thinner and cooler the higher we climb. True airspeed increases and so do tailwinds, if you’re headed in the right direction. Higher altitudes also bring with them some physiological changes we should already know about, like hypoxia—the lack of oxygen—which demands we use supplemental oxygen in unpressurized aircraft. The altitudes and hypoxic effects vary with the individual and duration, but it’s a good idea to start thinking about supplemental oxygen at and above 10,000 feet msl.

In fact, the proportion of oxygen in the atmosphere at, say, 25,000 feet is the same as it is on the surface—there’s just less of it because the air is thinner. The lower atmospheric pressure at altitude, which is one way we measure altitude, can affect the human body in ways we may not realize. For example, very few people know that flying can cause something called decompression sickness. It’s important for pilots to know when it’s likely, how it feels (so you can recognize it), what to do about it and—most important—what risks it entails.

Impairment

You may have learned that your brain is sometimes important to safely piloting an aircraft. The old saw, “Flying is hours of sheer boredom interrupted by moments of stark terror,” is a humorous saying that holds a truth: Normal, brief flights in calm conditions are easy. But at particular moments, we need clear thinking, quick analysis and accurate physical reflexes. Safety, then, depends on an unimpaired brain.

Most pilots know that insidious brain-function impairment will sneak up on us from fatigue, hypoxia, hypothermia, dehydration and heat stress. Simply knowing this, however, is a far cry from recognizing impairment, because human brains lack an idiot light for the user. Instead, our brains are designed to make do with what they have. This kind of impairment is commonly seen in our friends after a couple of drinks: “Nobody is more interesting after three drinks, but they all think they are,” is another appropriate saying.

Impairment only matters when peak performance is suddenly necessary, using either intellectual or physical skills (the brain handles both). Most pilots also don’t know that altitude is hard on the brain, much like a concussion, with impairment that can last several days.

Diving And Flying

One bottom line is this: Any altitude risks severe decompression sickness (DCS) after scuba diving. A common scenario is diving in the Bahamas, and then flying back to Florida. This form of DCS is different than when flying to high altitudes. But I’ll come back to it shortly.

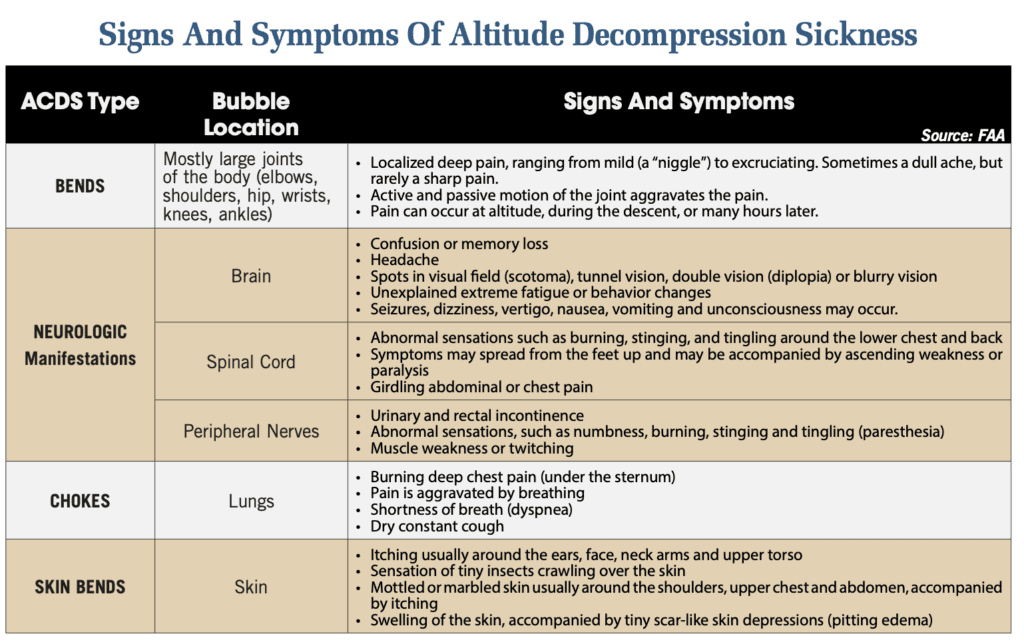

Flying at or above a 22,000-foot pressure altitude (FL220)—drivers of turbocharged, non-pressurized airplanes, are you listening?—consistently causes decompression stress in the brain, with symptoms present in most pilots. Symptoms? Eighty percent of the pilots surveyed experienced joint pain; 20 percent of the pilots experienced more subtle symptoms, detailed below. Let’s call this altitude decompression sickness (ACDS) because it’s different.

The main risk of ADCS is poor decision-making under stress and bad landings, essentially the same risks as dehydration, hypoxia, fatigue and thermal stress.

Doing A Survey

In 2021, Michael F. Harrison and his colleagues published the results of having surveyed every unpressurized GA flight in the U.S. above FL180 during 2018. They identified the flights with FlightAware data. The aircraft were mostly Beechcraft (11 percent), Mooney (22 percent) and Cirrus (63 percent—39 percent of the flights were to or from Duluth, Minnesota, where Cirrus is headquartered). They were able to query 46 pilots, of whom 60 percent had flown above FL180. Eighty-four percent of these pilots reported experiencing symptoms typical of ADCS. None were aware of the condition before the survey.

What Causes ADCS?

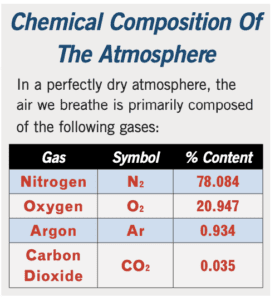

The atmosphere’s composition—mostly nitrogen and oxygen—is presented in the table at left. Our bodies steadily consume the oxygen, but are not designed to use or expel nitrogen. At low pressure, the nitrogen forms microscopic bubbles in blood and organs that can damage tissue. In diving, nitrogen is driven into body fluids by pressure of the water surrounding us and, without planned decompression, will form bubbles on the way up, as pressure is reduced. Diving tables assume that people return to sea level. In aviation, the atmospheric pressure at FL220 and above will cause bubbles to form in most people who began flight near sea level. This happens at much lower altitudes in people who have been diving.

What Damage Is Done?

Ignoring the minor injuries, divers with DCS can have permanent spinal cord injury, including paralysis or death from “circulatory compromise,” which is complicated. Aviators rarely die from ADCS, but can incur brain injury on hours-long high-altitude flights. This injury is similar to traumatic brain injury. Rarely has this damage prevented later medical certification.

The most serious ADCS occurred in U-2 pilots, with a cockpit pressure altitude of around FL290, who flew nominal 12-hour missions over Iraq and Afghanistan, which often were shortened by ADCS symptoms. Life-threatening incidents of ADCS and brain injury led to expensive modification of U-2 cockpits to permit a pressure altitude of 15,000 feet.

Can ADCS Be Prevented?

Yes, ACDS can be prevented, ideally by avoiding cockpit altitudes above FL210, though that is not a hard, reliable limit. The risk can be reduced by breathing 100-percent oxygen for one to four hours before flight and throughout such a flight, and afterward for as long as any ADCS symptoms persist. This is pretty much impossible outside the military. A cockpit at a pressure altitude of less than 20,000 feet greatly reduces the risk. The best expert, Dr. Andy Pilmanis, has written that no one should fly an unpressurized aircraft above FL250 and expect to avoid ADCS.

Decompression sickness during flight and after diving has occurred at every reasonable altitude, even as low as 1000 feet msl. The standard recommendations for flight delay after diving reduce but do not eliminate DCS risk. If a pilot has been flying in Class A airspace while unpressurized, or at any altitude within a few days after diving, always consider weird symptoms possibly to be ADCS and investigate.

Treatment

Brain, chest or eye symptoms must be treated with hyperbaric oxygen (HBO). Immediately call the Divers Alert Network 24-hour hotline at 919-684-9111 to identify the nearest feasible treatment center. They will ask, “What is the problem?” Don’t tell the whole story, simply say, “Aviation decompression sickness.” They know how to respond. A list of accredited hyperbaric centers is at tinyurl.com/HBO-Feb2023. Most larger hospitals have HBO centers for wound treatment. These are mostly single-person, small units; for severe DCS, a multi-person unit is better if one can be safely reached.

All ADCS should be treated by descending and breathing maximum oxygen to the ground. If symptoms are not completely resolved, then go on 100 percent oxygen for at least two hours once on the ground, and plan transfer to a HBO chamber during this time. Any recurrent symptoms warrant a trip to an HBO center wearing 100 percent oxygen. After DCS, no matter how mild, stand down for a few days. Research does not reveal how long that should be; perhaps at least three days.

The Bottom Line

Altitude-related ADCS is a risk for any pilot flying in the flight levels. Know the signs and be keenly aware during flight and for at least 24 hours afterward.

Dr. Daniel L. Johnson is a retired senior AME and internist. He holds an FAA commercial pilot certificate with instrument-airplane and glider ratings.