As my initial CFI checkride approached, I had been spending a lot of time in an airplane’s right seat, unlearning several years of flying from the left one.

One bright Saturday morning, my flying club was giving demo rides to prospective members, sort of a “you can learn to fly, too” event for professionals. I loaded three of them into a Skyhawk and blasted off for a nearby airport with me in the right seat, a new-member prospect in the left and two more candidates in the back. We flew to the other airport, landed and shut down.

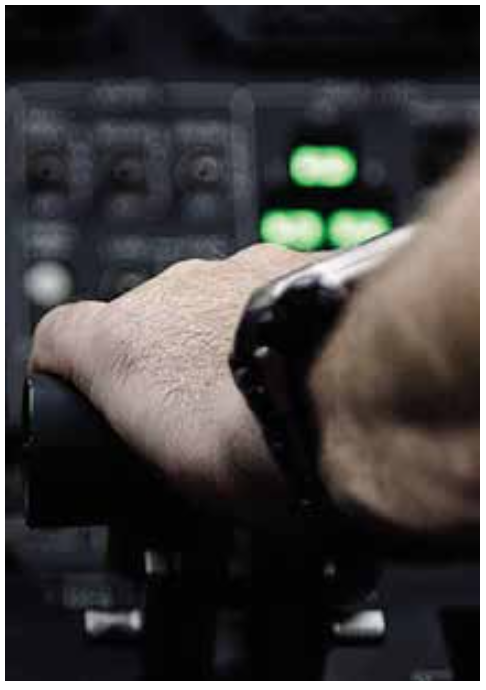

Then we did a bit of a fire drill, with the left-seater exchanging positions with one of those in the back. Rinse, repeat after flying to a second local airport. I flew from the right seat for all these legs without an issue, doing the landings and takeoffs, but letting the left-seater use the yoke, rudder pedals and throttle when we weren’t too low, to get the feel.

The third leg was back to home plate. This flight’s left-seater apparently had learned nothing from watching the other two, overcontrolling with a death-grip on the yoke, and little thought of what to do with the rudder pedals. Nevertheless, we arrived in the traffic pattern without undue drama and I took back the controls to do the landing.

Although the day started out calm and sunny, a slight, gusty breeze had kicked up, requiring a bit of a crosswind correction. No problem—I was almost a CFI and could do this in my sleep from either seat.

Sure enough, we experienced a gust as I was beginning the landing flare. I made the appropriate control inputs to compensate and eased off the throttle. We were maybe 10 feet off the runway, and I wanted this to be smooth. Right about then, the gust disappeared, with the airplane needing to find the few knots it suddenly lost. Naturally, I added some power and pitched the nose up to arrest the slight descent that resulted.

But I made those control inputs from the right seat, as if I was in the left seat: pulling slightly back with my left hand, pushing slightly forward with my right one. Which are precisely the control inputs you don’t want to make from the right seat when trying to arrest a descent. I pranged it onto the runway, but we could use the airplane again.

Muscle memory is a thing, and so is the law of primacy, which states that what is learned first is what is best remembered.

Have you encountered a situation or hazardous condition that yielded lessons on how to better manage the risks involved in flying? Do you have an experience to share with Aviation Safety’s readers about an occasion that taught you something significant about ways to conduct safer flight operations? If so, we want to hear about it.

We encourage you to submit a brief (500 words) write-up of your Learning Experience to Aviation Safety for possible publication. Each month, Aviation Safety publishes a collection of similar experiences sent to us by readers. Sharing with others the benefit of your experience and the lessons you learned can be an invaluable aid to other pilots.

You can send your account directly to the editor by e-mailing it to [email protected]. Put “Learning Experience Submission” in the subject line; add your name and daytime telephone number at the bottom of the e-mail.

Your report will be considered for publication in the Aviation Safety’s readers’ forum, “Learning Experiences,” and may be edited for style and length. Anonymity is guaranteed if you want it. No one but Aviation Safety’s editor is permitted access to the reports. Your name and telephone number are requested only so that the editor can contact you, if necessary.

While we can’t guarantee your submission will get published, we can guarantee that we’ll closely review and consider using it.

All Learning Experiences submissions become the property of Aviation Safety and may be republished.