There’s no question in my mind; instrument pilots who fly IFR without proficiency are an accident waiting to happen. They used to call it “competency” but the word, I suspect, has negative connotations that the FAA wanted to avoid. I say call it what it is. After all, what competent human would put his life—and the lives of his passengers—in jeopardy deliberately? That’s what a pilot who has not practiced IFR or is unfamiliar with the avionics in his aircraft does when he or she blasts off into cloud.

The IFR proficiency check (IPC) is a bit of a cross between a flight review and a certificate check ride, and my prescription for most light general aviation pilots is that you get one each year, whether your “currency” is there, or not. Why? Because most of us need the touch up.

Whether You Need It or Not

Let’s be clear: I’m not talking about the kind of proficiency dictated by FAR 61.57. We know by now that performing six approaches, holding procedures and intercepting and tracking using navigation systems every six months isn’t a full solution to the problem of remaining proficient in all aspects of contemporary IFR operations. The rule states that basically, if you can’t get the minimum of practice or actual experience in IFR every six months, you have another six months in which to get the practice (though you are barred from flying actual IFR during this time). After 12 months elapse from the last time you were current, you’ll need to go see a specialist—an instrument instructor—who can help brush up your skills and administer an instrument proficiency check (IPC). It’ll be noted in your logbook certifying that you have demonstrated you can fly safely in IFR conditions. At that point, for the sake of the rule, the time cycle for legal currency is reset for another six months, ad infinitum.

Big deal. Twelve hours of IMC, plus some approaches and a hold or three isn’t all that unusual for someone who flies, say, at least 100 hours a year in most parts of the U.S. But that doesn’t equate to proficiency, just compliance with the FAR. You really need an independent evaluation and an objective look at the kind of flying you’ve been doing.

Dirty Little Secret

Why is that? One simple truth: most general aviation IFR-rated pilots fly very little actual IFR. That’s defined as flight in less than three miles visibility (one mile in certain airspace) and within spitting distance, or actually within cloud.

There are a few GA pilots flying light aircraft who file IFR for every distant cross-country. They like the practice of being in the system, talking to ATC and if they encounter a cloud that isn’t too ominous, they can fly right through it and log a bit of “actual” IFR. But they can’t legally log all that VFR time as actual IFR, even though they participated in the system. They can’t log the ILS approach at the end of the flight, either, unless they had a view-limiting device in place and a qualified safety pilot, at the least, in the right seat. Don’t get me wrong; I’m not discouraging you from practicing your IFR skills in VFR conditions even without the view-limiting device. Just don’t log it as IFR—because it is not.

The problem isn’t that you file and fly IFR. The problem is that you’re probably not getting the IMC and approaches you need to remain legally current. The dirty little secret instrument pilots don’t tell those lacking the rating is it’s often unusual to spend much time in IMC, except when climbing or descending, and then it’s for not very long. Approaches in actual IMC count, too, but they can be just as rare.

A Case for Simulation

One flexibility the new airman certification standards did not take away is the ability to work out at least some of the required tasks for the IPC on the ground. Options include FAA-approved advanced aircraft training devices (AATDs) or a full-motion simulator. It is unlikely you have one of these devices at home. Even if you did, you’d need a flight instructor before you could legally use it for log-able experience.

But I’m a big fan of desktop flight simulation if it is done right. I encourage my clients to practice their most-rapidly perishable skills with desktop avionics simulators (all the big avionics makers offer them to customers). In fact, I insist that they spend some time with me on such simulations before we fly for the first time, even if it can’t be counted toward their IPC or flight currency.

For example, it helps to review the sequence for arming each navigation device for each different approach, holding pattern or procedure before hitting the noisy and distracting environment of the airplane cockpit in flight. If my client hasn’t had a lot of IFR experience in the last couple of months, the desktop simulation refreshes their memory for procedures and cockpit processes. It is these basic skills that make every other skill you’ll demonstrate on an IPC check possible. Brushing up on them in the calm of a ground-based office is considerably less frustrating—and far more economical—than burning through 100LL at 11 gph or more just to refresh your cockpit flow.

Contents of an IPC

Once upon a time, flight instructors and check airmen had some leeway regarding what was tested on an IPC. The practical test standards and its very new successor, the airmen certification standards, ACS, have changed that for good. In fact, FAR 61.57 makes the PTS mandatory for conducting an IPC. (Yes, we know there’s no longer a PTS applying to the airplane instrument rating, but good luck making that argument at the enforcement hearing.)

The new ACS takes the whole concept considerably further, without changing “the tolerances for any skill Task. Rather, the integration of knowledge and risk management elements associated with each Task is intended to enable a more holistic approach to learning, training, and testing.”

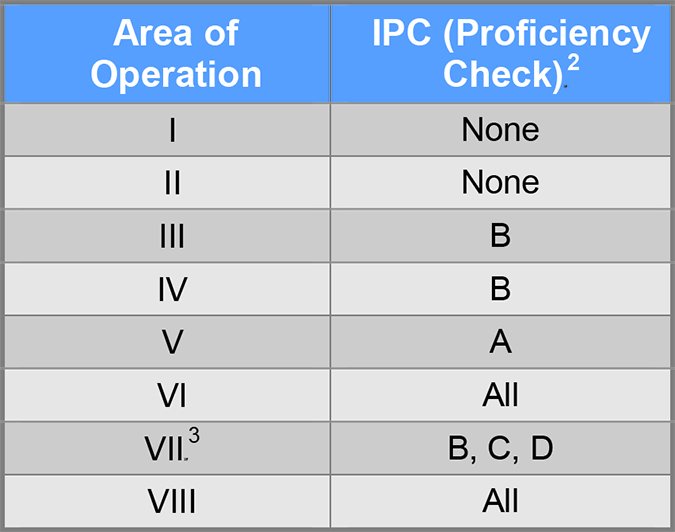

Appendix 5 of the instrument rating ACS dictates exactly what and how IPCs are to be conducted. The list is comprehensive. In addition to everyday IFR procedures like copying a clearance, holding and unusual attitudes, you’ll be asked to demonstrate DME arcs, missed approaches and circling approaches. If you fly a twin, you’ll be doing at least some of the IPC on one engine.

Simulators like an advanced aviation training device “can be utilized for the majority of the IPC as specified in the letter of authorization issued for the device. However, the circling approach, the landing task and the multiengine airplane tasks must be accomplished in an aircraft or full-flight simulator (level B, C, or D), according to the ACS.

How Most IPCs Go

You can’t “fail” an IPC in the same way you can a check ride (that’s how it is like the flight review) but there are highly structured and definitive sets of skills that must be demonstrated to check ride standards, and plenty of pilots I know discover quickly that they’ll need some touch-up flight instruction before they can get down to proficiently demonstrating the tasks required for an IPC endorsement.

Most general aviation light aircraft pilots, particularly single-engine pilots, opt to take their IPC checks in the cockpit of their own aircraft, and I think that is probably a good idea.

But here’s the thing: I’m not one of those flight instructors who meet up and just hop in an airplane with a client. (If you find one of those, take a moment’s pause.) Any smart CFII is going to ask to see your maintenance logs to make sure the airplane is legal. He or she will talk with you about the currency of your equipment (when was your last VOR check? How about your pitot/static and transponder checks?).

He’ll use the ground time to get a feel for how much you understand about the IFR system, and how much you remember about the particulars. Things like MEAs and MOCAs (minimum en route and minimum obstacle clearance altitudes) are still must-know information, as are no-radio procedures. You’ll talk about your personal minimums, which most likely are higher than what FAR 91 requires for IFR pilots.

Your instructor might dictate a complicated clearance and have you write it down and read it back, then discuss how you’d set up the airplane to carry out the ATC commands with your avionics. There should be a conversation about backup instrumentation, how it works and when as well as how you’d use it.

As a CFII, I get to fly in airplanes that are set up with anything-but-standard avionics configurations all of the time. There are a lot of hybrid analog-digital light aircraft instrument panels lurking out there right now, and each one was wired differently. I’ll want to talk about your airplane’s panel, and in the process get a feel for how much you know about the equipment you have. If your CFII just glances at the panel while you are pre-flighting and then says, “Let’s go!” again, you may want to take a moment and show him the panel, especially if there are any “gotcha” switches lurking there.

The Specs

As the sidebar on the opposite page details, the new airman certification standards (ACS) for the instrument-airplane rating may be the source of some surprises for you and your CFII. Thanks to FAR 61.57(d), using the ACS is mandatory, as are certain of the tasks it presents. There are some seasoned flight instructors, and probably even a couple of designated examiners who are seething after reading the ACS, precisely because it is so detailed in its instruction toward how any maneuver should be performed. They’re annoyed because it leaves an instructor’s discretion completely out of the picture. Then again, there are a lot of young flight instructors out there who will appreciate the detail and structure the ACS provides.

So, exactly what has changed? As a CFII I’m pleased to see the specifics introduced surrounding the critical topic of risk management. That said, the ACS essentially dictates how I must introduce and test the topic. I’m a creative type who doesn’t always color inside the lines, so the rigidity I see in the ACS chafes. Then again, being a creative type, I’ll find my way through and around the document. My clients will always receive the thorough IPC they have come to expect when they hire me and, if I’m really good, they’ll hardly notice we are working inside the confines of a new doctrine.

Prepping Yourself

Ideally each of us IFR pilots would stay current. Period. We’d be up there flying weekly like the airline guys, churning across the sky and around the bad weather, popping up through and down through benign stratus cloud everywhere.

And then there is real life, where most of us live. My solution to the currency problem is to practice a bit of IFR flying every time I’ve got someone qualified as a safety pilot in the right seat of my airplane. Maybe we do one approach, or some holding. Even 10 minutes of IFR practice in each flight helps.

When I’m alone I’ll work in the system, using ATC, and I’ll demand check ride standards for my straight and level flight (that’s minus zero, plus 50 feet on altitudes for me). As for turns? Standard rate. Climbs at best available rate until the last 1000 feet, then at 500 fpm to a precise level off. Descents? The same.

Finally, I make a point of using all of my equipment, and refreshing myself about backup and partial panel procedures in my own aircraft. It’s got three independent ADHRS for attitude and heading reference, a pitot-static system for airspeed and altitude, two alternators and three backup batteries for electricity, three GPS navigators (two can be coupled to the autopilot) and the usual complement of nav/coms and ILS systems. It takes a lot of practice to remember how they all work together, and how they work apart, too.

And if I can’t get out of the office? I fire up my desktop flight simulation and give it 20 minutes. That’s time for an approach and a miss with a hold entry, or time to execute one complete SID or STAR.

It isn’t as onerous as it sounds, and even if I’m flying once a month, as opposed to my ideal frequency of once a week, this practice regime keeps me limber and confident that I can handle the IFR flying that is within my personal minimums.

Most important, I adhere to my own prescription, and make sure that I schedule a yearly IPC, whether my logbook says I’m current, or not.

Once A Year?

At the top of this article, I argued that instrument pilots should go get an IPC at least once a year, whether they’re legally current or not. Part of my rationale involves the fact most of us just don’t spend enough time in for-real IMC or shooting for-real approaches, so it’s hard to remain current, much less proficient.

But there are other reasons to get out with a double-I once a year in search of an IPC, including the speed with which the underlying IFR system has been changing recently. The ACS itself is an example, but there are many more lurking out there. Just because your EFB is up-to-date on the latest system changes, it doesn’t mean you are.

Proficiency often is its own reward, but today’s dynamic cockpit environment and the enhanced situational awareness it offers demands we invest more of our hard-earned time each year than we might want. Thanks to the new ACS, at least we might save some time knowing the tasks we must perform to get through an IPC now are mandatory and well-defined.

Amy Laboda is a freelance aviation writer who holds an ATP and CFII. She and her family fly an RV-10 and a Jabiru-engined Kitfox.

This article is is exactly why general aviation pilots are leaving aviation. The regulations are unnecessarily complicated just like the weather briefing for a flight is 50 pages long