Somewhere back in the typical GA pilot’s mind is the idea of flying a personal airplane over long distances. Maybe across a continent, maybe an ocean. Or around the world. Part of the idea is visiting distant destinations and seeing foreign lands from the perspective only a personal airplane can offer. Another part of it is the challenge, which can be substantial; part of it is bragging rights; part of it is just because you can. However common the idea of flying around the world may be, the typical GA pilot rarely follows through. Whether due to time constraints, finances, lack of a suitable airplane or other responsibilities, the obstacles are just too daunting for the typical GA pilot.

But Adrian Eichhorn isn’t your typical GA pilot. For one, he’s a 16,000-plus-hour ATP whose day job is flying an Airbus A320 for a major airline as first officer. He’s also an FAA A&P/IA, as well as a flight instructor. He’s type-rated in the A320, Gulfstream GII/III/IV and the Aero Vodochody L39, among others. In an earlier life, he flew for the FAA, from its Hangar 6 location at Washington National Airport, and provided flight and ground instruction to the agency’s flight crews and top officials. And he’s a Bonanza owner, which is how I know him. Earlier this year, he flew that Bonanza around the world. After he got back and had the chance to rest up, we talked about his journey, about how he managed the substantial risk of flying a piston single across hundreds of miles of ocean at a time, and about some of the operational details. Here’s what I learned.

Lee Stikeleather

Rules Of Three

The table to the right details the route he flew, how long it took and his average groundspeed. Many of the legs had great circle distances in excess of 1500 nm, with one, from Honolulu, Hawaii, to Oakland, Calif., longer than 2100 nm. That meant non-stop legs of 10-plus hours. Over water. In a piston single. Solo. How did he manage the risk?

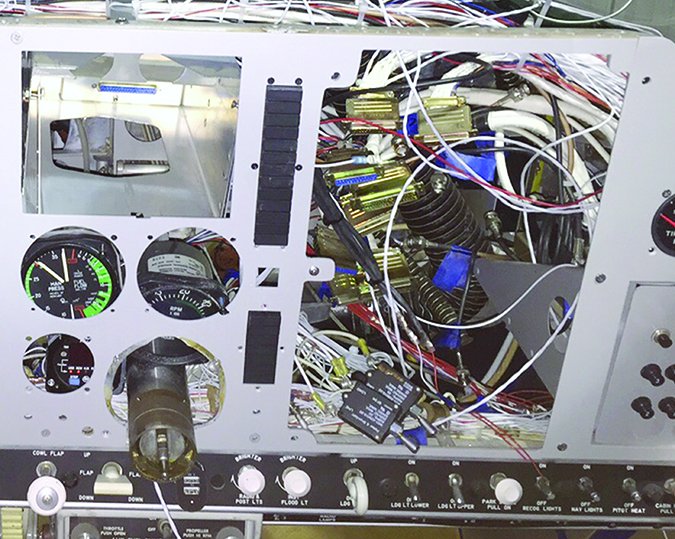

For one, the equipment was in top condition. As the sidebar on page 18 highlights, Eichhorn has spent most of his free time over the last four years completely restoring his airplane. He did most of the work himself, including the sheet metal, avionics installation, rebuilding the engine, installing new cylinders and ensuring it all played well together. Several shakedown flights later, the airplane was in better condition than when it left the factory.

But aside from flight planning and operational concerns, which were handled by two experienced pilots back in the U.S. he worked with via a satphone, he organized the everyday risks he faced into three broad categories: fatigue, complacency and distraction. Flying 10-plus-hour legs by itself is fatiguing, but so is flight planning, ensuring the airplane is fueled and dealing with airport personnel and ATC systems largely unfamiliar with—and often hostile to—piston-powered general aviation aircraft. He combined acute awareness of those risk factors with what he calls his “three strikes rule.”

Take for example a typical GA pilot, headed off on a flight. He arrives at the airport only to find he’s left his hangar key at home. Regardless of how he gains access to the airplane, that’s Strike One. Another issue, perhaps an expired navigation database or needing to add a quart of oil, might be Strike Two. By this time, with these two deviations from normal, any third problem—a fouled spark plug discovered during the run-up, for example, or weather deteriorating faster than predicted—would be Strike Three.

As Eichhorn told us, “You have to make the commitment to not fly at strike three, or re-evaluate and take the necessary steps to not only address the problem, but then step back and analyze what’s left. In all the drama of finding the hangar key and deciding you don’t need a current database for this flight, what else did you forget? “Pilots are Type A people,” he told us, “who go when sometimes we shouldn’t.”

Eichhorn got to Strike Three one day when a country refused his flight plan and would not allow him or his Bonanza into its airspace. While it’s likely refiling the flight plan with slightly different routing would have been acceptable, the smarter decision, he told us, was to simply cancel that day’s flight, remain overnight and plan the next day’s leg for a different destination. Which highlights another feature he built into this project: flexibility. He had plenty of time and wasn’t facing deadlines, so he didn’t have to deal with the pressures of meeting his or anyone else’s schedule.

Flight Planning

Most takeoffs were heavy, with the fuel aboard to not only reach a destination more than 1000 nm away but also with adequate reserves. While the airplane performed perfectly, it’s always best to not need extra performance but have it anyway. That meant takeoffs at dawn, when temperatures were coolest. To be airborne at sun-up meant awakening around 0300 local time, often adding further stress and fatigue. Factor in sleeplessness from anticipating the next day’s flight and it’s easy to overlook something before the wheels are in the well.

Fuel is always a primary concern on any long-range trip, and Eichhorn told us he carried “way more gas than I needed.” He usually landed with a minimum of 40 gallons aboard, or 3.5 hours. Since it takes gas to haul gas, the trade-off is slower cruise speeds and reduced climb rates. Still, his block times and average groundspeeds were both acceptable and expected.

While he’s experienced at international flying, he wanted an extra set of eyes looking over his plans. He got that, and more, in the form of two experienced pilots back in the U.S., John Whitehead, who monitored worldwide weather and Eichhorn’s own flight planning, and Dr. Bill Compton, who oversaw not only the airplane’s performance but also the pilot’s. Before every leg, all three had the same operational information and compared notes on the upcoming flight.

Of course, the tools to which U.S.-based pilots have grown accustomed—ForeFlight, for example, or in-cockpit Nexrad weather radar—just aren’t available outside North America. “We take for granted so much in the U.S. Elsewhere in the world, there’s little en route weather data between destinations,” he told us. If you want airborne weather radar, as is available in the U.S. via ADS-B In, you have to take the radar equipment with you because it just doesn’t exist in other countries. No, Eichhorn’s Bonanza doesn’t have its own radar, so there were some tense moments.

Eichhorn used FliteStar, a laptop-based flight-planning program from Jeppesen, which helped sponsor his trip. Despite his previous international experience—he’s flown the FAA’s N1 Gulfstream IV to Moscow and back—largely involving operations on which someone else performed the flight planning and obtained overflight permits, Eichhorn wanted to do it himself. “I wanted to experience how difficult the flight planning would be, since every trip I make after this would be relatively easy.”

Jeppesen’s FliteStar is an older flight planning program, but what it lacks in user interface and friendliness it makes up for in flexibility, Eichhorn told us. It took him roughly two hours to plan out each leg, which always ended at an airport known to have aviation gasoline available, either from a truck or in 55-gallon drums. He didn’t follow the most direct route, and probably used the most expensive airports but in each country he visited, but he did plan the basic trip around avgas availability.

Crossing from one flight information region, or FIR, to another is analogous to being handed off from one air route traffic control center in the U.S. to another one, but that’s where the similarities end. To file an acceptable flight plan crossing from one FIR to another, it must include an intersection at the FIR boundary and the expected crossing time. Even so, Eichhorn said his initial flight plans always were rejected the first time, with little or no guidance on how to fix it. Despite the lack of en route weather information and the time it took to fly most legs, Eichhorn told us he never had to divert, always landing at his intended destination.

Equipment, Reliability and Survival Gear

Eichhorn’s years of hard work restoring and improving his Bonanza paid off: He didn’t even have to add air to the tires during his trip. Even though he’s an A&P, he carried minimal tools and spare parts, maybe 15 pounds’ worth. In addition to two panel-mounted Garmin GPS navigators, he carried two iPads loaded with Jeppesen’s FD Pro EFB software, neither of which ever lost position, even hundreds of miles from land.

His additional equipment included two life rafts; a six-person version with a survival kit and a much smaller two-person raft. In addition to the airframe mounted ELT—which would be useless when it went down with the plane—he also carried two personal locator beacons, and a Breitling Emergency watch, which has its own 121.5/406 MHz ELT built-in. There were two personal flotation devices aboard, plus a satphone, flares and flashlights in a throw bag, ready to be first out the door in a ditching.

Yes, he also carried an immersion suit, but didn’t wear it, placing in-flight comfort and hydration ahead of the unlikely need to ditch and egress the airplane. In his view, staying fit and alert while airborne minimized the likelihood of ditching and the need to wear the suit. The only thing he wish he had taken? A portable printer, which would have made his initial flight planning and the inevitable revisions easier to accomplish in a far-flung hotel room or the cockpit.

Timing, Physiology and What’s Next

As mentioned earlier, Eichhorn timed his flights to depart at dawn. Sometimes, inevitable delays took a toll, but the idea of departing early had as much to do with cooler morning temperatures and better performance from his normally aspirated engine as it did the other end of the flight. Flying eastbound, away from the sun, the days are shorter, even at only 150 knots. “You run out of sunlight, so the last three or four hours are at night,” he told us. “The reality of ditching at night and surviving is really pretty unlikely. But the only way to mitigate the risk is don’t fly,” he added.

While many pilots might find it impossible to stay alert in the cockpit for eight, 10 or 15 hours at a time, that wasn’t a problem, he told us. His routine was to switch fuel tanks every 30 minutes, at 15 and 45 past the hour. Meanwhile, position or ops normal reports were required at the top and bottom of each hour, so there was something important to do every 15 minutes, he told us. “That keeps you engaged,” he added. He never took a nap in the cockpit, “mostly from fear of missing something important; I couldn’t sleep even if I wanted to.”

Now that he’s worked out the kinks in his long-distance flying, what’s next, we asked. Maybe fly around the world from pole to pole, he told us. What would he do differently next time, if there is a next time? Airborne weather radar would be extremely useful, he told us, but there’s no way to fit it to his airplane. Maybe he’d carry more cash, since exorbitant landing/handling fees and fuel prices were the rule, not the exception. “Once airborne, by myself, there’s a certain serenity from doing this in your own airplane,” he told us. Is there any one thing that helped make the trip successful? “Not having a timeline, knowing I don’t have to fly tomorrow and not pressuring myself to complete the trip. I was in the right frame of mind,” he told us. And that’s something that applies to all our flying.

Jeb Burnside is this magazine’s editor-in-chief. He’s an airline transport pilot and owns a Beechcraft Debonair.