Given enough time, it seems any discussion of general aviation involving non-pilots always will come around to someone asking, “What happened to JFK, Jr.?” John F. Kennedy, Jr., of course, was the only son of former U.S. President John F. Kennedy, who was assassinated in Dallas, Texas, on November 22, 1963. For a week or so in July 1999, coverage of the flight resulting in JFK, Jr.’s death—and of his two passengers—dominated the U.S. media. It remains one of the most high-profile U.S. general aviation accidents and, for non-pilots, the JFK, Jr., accident is Exhibit A why personal airplanes are “dangerous.”

After his airplane was reported overdue and missing, it took three days for searchers to locate the underwater crash site using side-scan sonar, and cable news breathlessly reported every development. This media event practically begged viewers to ask themselves, “If someone with JFK, Jr.’s resources can’t fly a well-equipped small airplane, what chances do I have, or the person I met last night at that cocktail party?” So, what to tell your in-laws or dinner-party guests, that’s both accurate and reassuring? Is there a non-technical way you can explain what happened? Most important, what can we learn from it, and how can we prevent what happened when it’s our turn?

The Basics

The date was July 16, 1999. At 2038 local time, some 24 minutes after sunset, the Piper PA-32R-301 Saratoga II HP piloted by John F. Kennedy, Jr., was cleared for takeoff by the tower at the Essex County Airport in Caldwell, N.J. (KCDW). Kennedy was in the left seat of the airplane he’d owned for some three months. In the rear-facing second row of seats were his wife Carolyn Bessette and her sister Lauren. The three were heading to the Martha’s Vineyard (Mass.) Airport (KMVY) for the weekend to attend his cousin’s wedding.

Kennedy acknowledged a right-downwind clearance to depart KCDW’s Class D shortly after takeoff. As he did not request VFR flight following from any of the facilities along the route, that was the flight’s last contact with ATC. According to radar data, the Saratoga proceeded roughly northeast at altitudes varying between 1200 and 1900 feet msl until approximately 2051. By then, the Saratoga had turned to a more easterly course, eventually going feet wet over the Long Island Sound. This routing kept the Saratoga clear of the Teterboro, N.J., Class D and below a tier of the New York Class B airspace. After turning to the east, the flight began climbing, eventually leveling at 5500 feet msl at around 2050.

The Crash

The Saratoga proceeded out over the Sound with land just off the left wing, level at 5500 and evidently on autopilot, given altitude fluctuations and heading changes earlier in the flight. At about 2133 local time, a descent was initiated, taking the airplane to 2100 feet by around 2138. Groundspeed during the descent averaged around 160 knots. By this time, the airplane was over the Atlantic Ocean, east of Rhode Island Sound, and between the southernmost part of Massachusetts’ mainland and the island of Martha’s Vineyard. What happened next is well-documented.

By 2139, the airplane had regained some of its altitude, climbing to approximately 2200 feet msl. It remained there for a few seconds, momentarily topping out at 2300 feet. In less than a minute, two things happened. First, the airplane began descending at a high rate. Second, the last radar return was recorded, at approximately 0140:40 and 1100 feet. Simulations performed by the NTSB estimate the airplane hit the water in excess of 250 KIAS.

According to the NTSB, “About 34 miles west of Martha’s Vineyard Airport, while crossing a 30-mile stretch of water to its destination, the airplane…entered a right turn. During this turn, the airplane’s rate of descent and airspeed increased. The airplane’s rate of descent eventually exceeded 4700 fpm, and the airplane struck the water in a nose-down attitude.” The NTSB’s documentation of the cockpit instruments found the airplane’s flight command indicator displayed a right turn of 125 degrees of bank and a 30-degree nose-down pitch attitude.

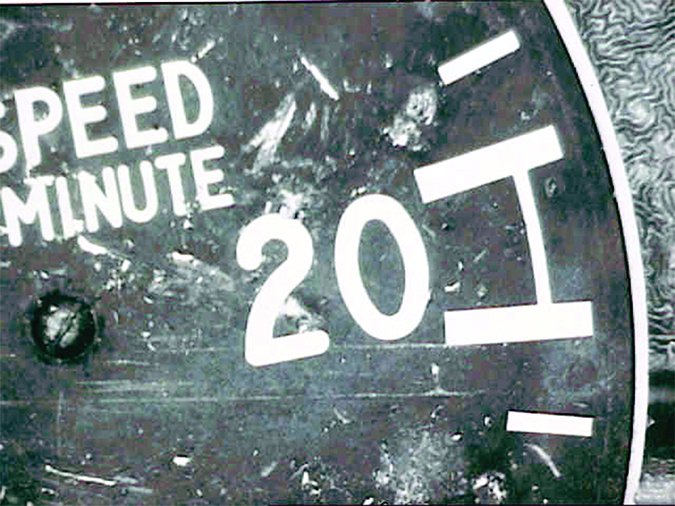

The images at left are from the NTSB’s docket on the JFK, Jr., crash and show witness marks created during the accident sequence on the faces of the airspeed indicator and vertical speed indicator. At bottom, the tachometer needle is stuck in place. This evidence corroborates airplane performance estimated from radar data.

The Weather

In some ways, the weather between New York and Martha’s Vineyard was typical for summertime in the northeast U.S. There was little cloud cover, but the summer’s haze had reduced visibility to as little as six statute miles. Martha’s Vineyard (KVMY), for example, was reporting clear skies and between seven and 11 statute miles of visibility. Block Island, R.I. (KBID), south of the airplane’s route of flight and at the east end of Long Island, was advertising clear skies and 10 miles; Bridgeport, Conn. (KBDR) showed clear skies and light winds, with visibility varying between six and eight statute miles.

Over the Long Island Sound, the same conditions persisted. According to the NTSB, “Other pilots flying similar routes on the night of the accident reported no visual horizon while flying over the water because of haze.”

The NTSB quotes the KMVY ATCT manager as saying: “The visibility, present weather, and sky condition at the approximate time of the accident was probably a little better than what was being reported. I say this because I remember aircraft on visual approaches saying they had the airport in sight between 10 and 12 miles out. I do recall being able to see those aircraft and I do remember seeing the stars out that night…To the best of my knowledge, the ASOS was working as advertised that day with no reported problems or systems log errors.”

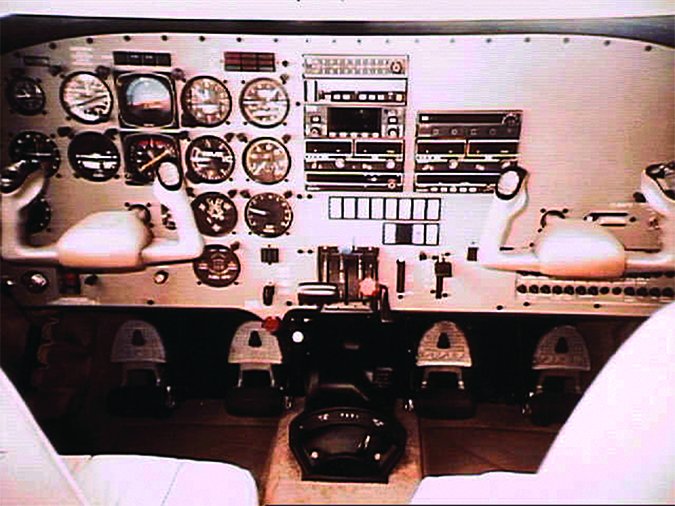

The Airplane

Kennedy owned the 1995 Piper Saratoga II HP he was flying, having traded up from a Cessna 182 Skylane about three months earlier. It was typically equipped for its day, with a Bendix/King 150-series autopilot, a Bendix/King KLN-90B GPS navigator with a basic moving map, two Bendix/King KX-165 nav/comms and a Bendix/King KR-87 ADF.

According to the NTSB, the KLN-90B’s navigation database had expired on November 4, 1998. A wire connected circuitry of a 3.6-volt lithium battery was separated. The lithium battery provided electrical power to retain the nonvolatile memory of the GPS receiver and required a minimum of 2.5 volts. The battery voltage was measured to be 0.2 volts, and the memory had not been retained.

The Pilot

John F. Kennedy, Jr., began his flight training in 1982. By September 1988, he had flown with six different instructors and logged 47 hours. Of those hours, 46 of them were dual instruction; one hour was solo. There were no more entries in his logbook from September 1988 until late 1997.

Beginning in December 1997, Kennedy obtained training toward his private pilot certificate from Flight Safety International (FSI) in Vero Beach, Fla. By April 1998, he had flown about 53 additional hours, 43 of which were with an instructor aboard. According to the NTSB, the instructor who prepared Kennedy for his private checkride stated he had “very good” skills for his level of experience.

Kennedy earned his private pilot certificate in April 1998. He did not have an instrument rating. He received a complex airplane endorsement in the accident airplane in May 1999, shortly after buying it. He held a second-class FAA medical certificate issued on December 27, 1997. It had no limitations.

His most recent/current logbook was not located. Using an older logbook plus training records, information from his flight instructors’ logbooks and statements from other instructors and pilots, the NTSB estimated Kennedy’s total flight experience, excluding simulator training, was about 310 hours, of which 55 hours were at night. However, Kennedy had relatively little experience without an instructor aboard. The NTSB estimates he had only 72 hours of flight without an instructor riding shotgun.

According to the NTSB, “The pilot’s estimated flight time in the accident airplane was about 36 hours, of which 9.4 hours were at night. Approximately 3 hours of that flight time was without a CFI on board, and about 0.8 hour of that time was flown at night, which included a night landing.”

Kennedy was no stranger to the route from KCDW to KMVY. The NTSB again: “In the 15 months before the accident, the pilot had flown about 35 flight legs either to or from [KCDW} and [KMVY]. The pilot flew over 17 of these legs without a CFI on board, including at least 5 at night. The pilot’s last known flight in the accident airplane without a CFI on board was on May 28, 1999.”

On March 12, 1999, Kennedy passed his instrument-airplane written exam and on April 5, 1999, the pilot returned to FSI to begin training for the rating. Before the accident flight, he had completed 12 of the 25 lesson plans. His primary instrument instructor at FSI felt his progression was normal and “he grasped all of the basic skills needed to complete the course” with the exception of VOR and ADF orientation. The instructor stated Kennedy “had trouble managing multiple tasks while flying, which he felt was normal for the pilot’s level of experience.”

According to the NTSB, the instructor who endorsed Kennedy’s logbook for complex airplanes reported the Saratoga’s autopilot “turned to a heading other than the one selected” on one or two occasions. The behavior “required the autopilot to be disengaged and then reengaged. The instructor stated “it seemed as if the autopilot had independently changed from one navigation mode to another. He also stated that he did not feel that the problem was significant because it only happened once or twice.”

Probable Cause

The NTSB determined the probable cause(s) of this accident to include: “The pilot’s failure to maintain control of the airplane during a descent over water at night, which was a result of spatial disorientation. Factors in the accident were haze, and the dark night.”

On paper, this accident shouldn’t have happened. Despite most of his time being in a training environment, a typical 310-hour instrument-rating student in a well-equipped airplane should have had no problem with this flight. The airplane was in good condition, the pilot was current, including at night, and the weather was decent VFR. But there was no visible horizon.

From the radar data, it’s likely Kennedy was cruising on autopilot. The two-axis autopilot aboard Kennedy’s airplane had an altitude hold mode, but it was not configured for climbs and descents to preselected altitudes. To climb or descend, the autopilot’s trim system could be used to establish a pitch attitude. His descent began right about the time the airplane was out of sight of lit structures and over open water.

For some reason—maybe the annoying mode change an instructor reported—the autopilot was disengaged before the pilot was ready to take over. Perhaps a fuel imbalance aboard the Saratoga, which carries some of its gas well outboard on each wing, surprised him upon taking the yoke. Regardless, he never made the transition to flying the airplane on instruments in reduced visibility, at night and with no horizon.

This probable cause statement has two phrases we see time and again: “failure to maintain control” and “spatial disorientation.” It’s nothing new, and it doesn’t look like it’s going away any time soon.

Jeb Burnside is this magazine’s Editor-in-Chief. He’s a 3200-hour instrument-rated ASEL/ASES/AMEL commercial pilot and aircraft owner.

Kennedy deciding to take off right before dark, an area that is regularly sock in with haze and fog, to fly over the ocean, away from the coastal lights was just a REALLY bad idea. It was such a bad idea, I’m wondering if his training was adequate. As in, maybe his celebrity and being such an A type personality maybe kept his instructor from talking to him like any other student.Because even before I was a student I was an aviation fan and knew what SD was and how it can instantly turn a flight into a nightmare.- I wonder if he was ever taught that the conditions that cause SD, combined with inexperience, plus external factors, like the pressure to get yourself and others somewhere (wedding) can quickly lead to a tragedy. Him taking off without an instructor for such a short flight was a terrible idea, but then he also kept going, even as it was getting darker, more hazy, and as the lights of the city got further away – I’m still shocked he made such bad sexisions.

Lack of experience and a deplorable training record. 310 hours over 17 years?

Did the empty co-pilots seat leave plane before crash

I hear you Capt. Forrest…from what I also understand, Kennedy was actually just a part time pilot. Rarely flying, maybe once ever couple months, if that. Flying that little, even just four times a month, without a CFI, will lead to a unfortunate fatality.

Let’s compromise safety. Step 1, Take off after dark. 2, Fly over water at night. 3, Don’t get Flight Following. 4, Instead of staying at 5500 MSL while over water 30 miles east of KMVY, until above KMVY, descend to 2100 MSL over water 30 miles east of KMVY. 5, Do that descent at 2 kph above the Saratoga’s max cruise speed of 158 kph. 6, Don’t have a visual sighting of KMVY prior to descending down to it. 7, Take loved ones along a flight in an airplane for which you only have logged 3 hours solo, and only 0.8 of that time at night. 8, Fly VFR, at night, in less than CAVU, with no visible horizon. You can swear on the BIble you’re in VFR, but the fact is you really are in IMC, and are going to have no choice but to fly the plane on instruments. 9, Don’t be IFR rated, don’t attempt an instrument approach, descend into the soup mistakenly believing you can fly the airplane VFR all the way to the ground.

This is sacrilege but …….if I were Carolyn Kennedy I would have learned enough about flying to keep myself safe. Enough to say no, John, either the CFI is on board, or we’re not. See you tomorrow on Hyannis .

There were actually ten reasons, Kennedy shouldn’t have flown. I won’t cover all of them, however, according to AOPA..one, he was out drinking, the night prior, with little sleep..two, he got into a huge argument, with his wife..and three, he was still using crutches, when he got his cast, off his left leg. And most important..his CFI, offered to co-pilot..and he said, ” No, i go alone”..

Reliable Airport Taxi London Ontario ensures stress-free travel. With affordable London to Toronto Airport Taxi services and premium Toronto Pearson Airport shuttle options, we cater to all your transportation needs. Book London Ontario Airport Taxi today for executive travel solutions.