Fly enough IFR and it’s inevitable that ATC eventually will lose a flight plan. Maybe it timed out—you got delayed and you’re calling for a clearance much later than your scheduled departure. Maybe it simply got lost, was filed under a different callsign or some other error crept into the mix. It doesn’t matter, since without a clearance, you’re not departing IFR.

Depending on the controller and his/her workload, plus how professional you sound on the radio, ATC may offer to fix the problem immediately. A controller can prompt you for enough information to enter your plan into the system directly, without you needing to chase down someone else on the phone or another frequency to re-file. If you can do it with your cell-connected tablet and an EFB app, try it. Otherwise, you’ll have to figure out a way to contact Flight Service and file all over again. Of course, you can depart VFR instead of IFR. If the weather is good, that’s an option, and you can raise Flight Service on the radio once you’re airborne and file, then call ATC for the clearance. But when the weather is IMC or even if it’s just marginal, that’s usually not a good idea.

My current home plate is a VFR-only airport lacking any way to reach ATC on the ground except by telephone. I’ve obtained clearances both ways—via cellphone from the cockpit with the engine running and by taking off, getting enough altitude to call ATC and making the request. The former takes some time and can be iffy when cell coverage is poor. The latter at least gets me on my way, but only if the weather is good. When it’s not, ATC gets busy and I have found myself circling and waiting in a long queue before obtaining a clearance. And if it turns they don’t have my flight plan, I’m much worse off than before.

When ATC can’t find the IFR you filed—be honest!—it’s tempting to launch and deal with it in the air—at least you’re not sitting on the ground. That can be a good plan when the weather is clear and a million and you don’t need the clearance to get up and on your way. But it’s a really bad idea when the weather is less than good enough to allow you to depart and climb to your preferred cruising altitude without needing a clearance.

Ensuring Your Flight Plan Gets Filed

According to the FAA’s Aeronautical Information Manual, “parameters have been established to delete proposed departure flight plans which have not been activated. Most [ARTCCs] have this parameter set so as to delete these flight plans a minimum of 1 hour after the proposed departure time. To ensure that a flight plan remains active, pilots whose actual departure time will be delayed 1 hour or more beyond their filed departure time, are requested to notify ATC of their departure time.” To ensure your flight plan is waiting when you need it:

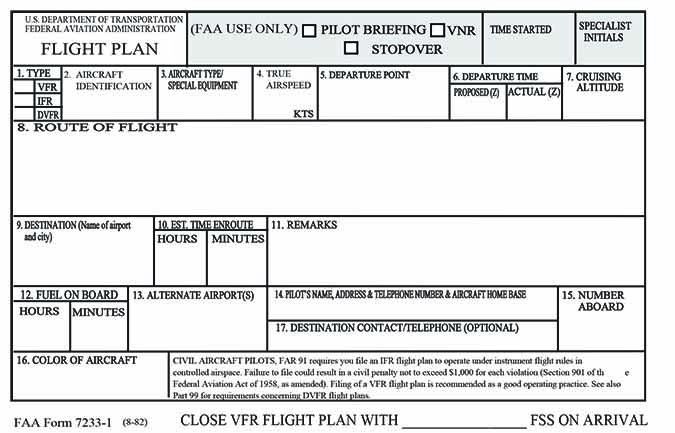

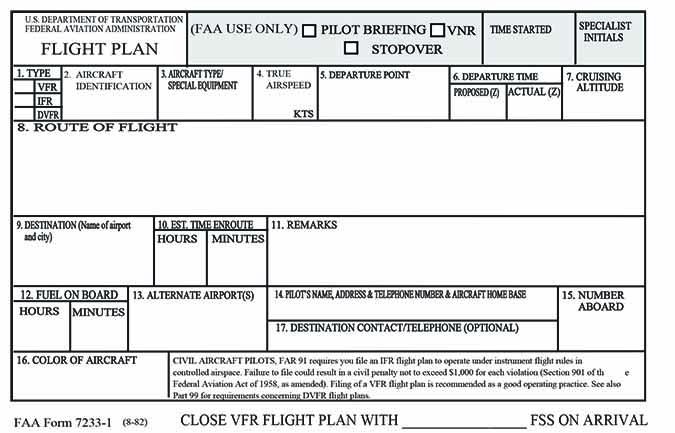

1. Use an EFB app or online service to properly format the flight plan, and obtain a receipt.

2. Ask the FSS briefer to read back the flight plan if providing it over the phone.

3. If you’re concerned the flight plan may have timed out, telephone Flight Service, the control tower or the controlling ATC facility to inquire before starting the engine(s).

Background

On October 12, 2014, at about 2240 Central time, a Beechcraft Model 58 Baron was destroyed when it impacted trees and terrain in Palos Hills, Ill. The private pilot and two passengers sustained fatal injuries. Marginal night visual conditions prevailed for the flight. The flight originated about five minutes earlier from the Midway International Airport (KMDW) in Chicago, Ill., en route to Kansas.

Earlier, at 2228, the pilot called for an IFR clearance but Midway’s controller was not able to access the flight plan, instead requesting the pilot provide him the information over the radio. The pilot then asked the controller if it would be easier to take off VFR and ultimately received a VFR clearance to depart. At 2234:44, the flight was cleared to take off.

Over the next four minutes, there were several routine communications between the accident pilot and Midway’s tower. During these communications, the pilot did not inform the controller of any difficulties. At 2240:21, the tower controller called the accident airplane due to a loss of radar contact but there was no response to repeated attempts. During communications between the pilot and controllers, no clearance for flight in instrument conditions was authorized.

Investigation

Radar track data show the airplane departed Runway 22L at Midway and began climbing on runway heading (220 degrees). At 2238:01, the airplane had a 130-knot groundspeed at about 2200 feet msl, some three nm from the airport. It then began a descent and turned 20 degrees left, to 200, followed by a right turn to an unspecified heading.

By 2238:38, the airplane was about 4.8 nm from KMDW and at 1500 feet msl. A climbing left turn began, with its radius decreasing until radar data ended. The airplane reached a peak altitude of 2800 feet msl at 2239:24. The final radar data point was at 2239:29 and 2400 feet. The calculated rate of descent between the final two radar points exceeded 5000 fpm.

The airplane impacted trees and terrain in a residential area. All major airframe components were contained within the wreckage distribution path, which was consistent with a near-vertical impact. Control system continuity was verified from all control surfaces to the cabin area of the airplane, but verifying yoke and rudder pedal continuity was not possible. All of the identified breaks in the airplane control system were consistent with impact damage or recovery efforts. Investigators could not find any pre-impact failure or malfunction in the airframe, control system, engines or propellers that would have prevented normal operation.

The pilot had slightly less than 500 hours total time, 114 of which were in multiengine airplanes. At 2238, Midway’s weather included six miles’ visibility in mist, a broken cloud layer at 1000 feet agl and an overcast at 1700 feet.

Probable Cause

The NTSB determined the probable cause(s) of this accident to include: “The pilot’s loss of airplane control due to spatial disorientation while operating in night, instrument meteorological conditions.”

According to the NTSB’s summary, “radar data indicated that the airplane penetrated the cloud layers during the accident flight. The pilot held the appropriate certificates and ratings for operation of the multiengine airplane in instrument conditions, but no clearance had been issued for operation in instrument meteorological conditions. The weather and light conditions at the time of the accident were conducive to the development of spatial disorientation.” The NTSB also noted the aircraft’s radar data was consistent with known effects of spatial disorientation.

It’s hard to understand how the instrument-rated pilot simply didn’t make the transition to instruments once he took off. How did he plan to perform the flight in the first place? It’s even harder to understand why the pilot apparently thought it would be better to control the airplane without referencing the flight instruments because he didn’t have a clearance. At a minimum, he could have declared an emergency and requested vectors back to the airport. If an enforcement action ensued, at least he could have attended the hearing.

AIRCRAFT PROFILE: Beechcraft Model 58 Baron

Engines: Continental IO-550-C

Empty weight: 3443 lbs.

Max gross TO weight: 5500 lbs.

Typical cruise speed: 195 KTAS

Standard fuel capacity: 136 gal.

Service ceiling: 20,688 ft.

Range: 1109 nm

Vso: 74 KIAS