By the time someone is sent for the instrument check ride, he or she is expected to know the emergency procedures in the appropriate POH as well as how to deal with failures affecting the airplane’s ability to fly in IMC. A cross-section of the bad news stuff is discussed during the oral portion of the practical test and demonstrated in flight. But what’s a little frightening is that the IFR check ride often marks the high point of an instrument pilot’s ability to deal with an emergency.

Once our ratings are obtained, what do most of us do? We begrudgingly take a flight review every 24 months, which we try to keep as short as possible. We try to stay instrument current by flying with a safety pilot so as to avoid having to obtain an instrument proficiency check. If we’re a lucky if infrequent pilot, we’ll combine the flight review with an instrument proficiency check. As we maintain currency, are we practicing the right things? What can we do to avoid looking stupid in an NTSB accident report? How should we identify and practice emergencies in a way that gives us the best chance of dealing successfully with the risks we face, but without spending so much money in the process that we can’t fly?

Start With A List

I like the approach I’ve seen some good doctors and CFIs take to their professions: sit down and make a list. It should include everything that can go wrong, a parade of horribles, as a law-school professor used to suggest. As you are reading this, why not open up a word processor and start your own list? You can save, edit and add to it for future reference Be creative and be sure to include those things that give you the heebie-jeebies.

How about such things as loss of control when maneuvering at low altitude while circling to land, or a circuit breaker opening and taking an important piece of equipment offline when you need it? Or a passenger suddenly becoming airsick during a time of heavy workload in IMC? Failure of various components of the electrical system, with the need to reduce electrical load; the old favorite, lost comms; sudden spatial disorientation; instrument failure and rapidly deteriorating weather as you start an approach.

An amazing number of the things that can go wrong or just fluster us as pilots can be rendered “ho-hum” rather than “omigawdimgonnadie” by just sitting in a comfortable chair and thinking them through before they happen. Visualizing things lets you come up with solutions and store them in the memory banks when you’re not under pressure. It’s also not a bad idea to look at the AOPA Air Safety Institute’s Nall Reports of general aviation accidents over the years to find the most common mechanical failure and the pilots botch their response and find new ways to hurt themselves. See the sidebar above for some tips.

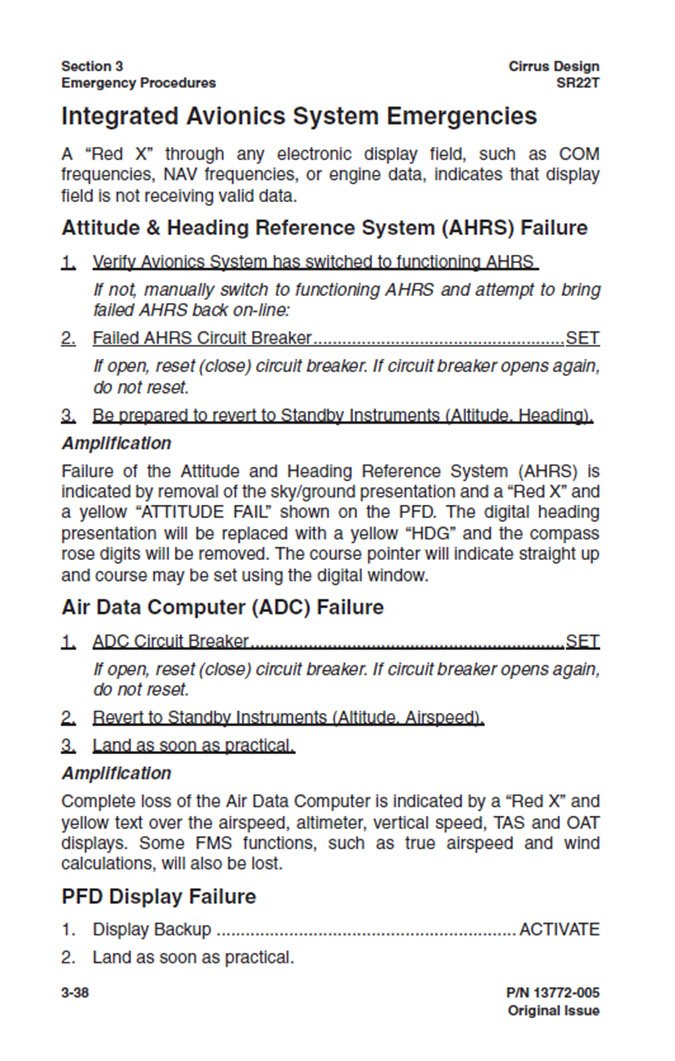

If we consider those problems and outline solutions for ourselves, we’re that much further along toward a happy ending when something goes wrong. It helps to have a copy of the POH or AFM for the airplane we normally fly handy while we’re doing this as it may just have the best way for dealing with the emergencies we are considering. It’s always a good reference for such and exercise.

The reality is that how we handle an emergency depends upon whether we’ve ever thought about it before it happens. If we’ve considered it, we’re halfway home, because we know what we want to do and then it’s just a matter of doing it.

Intellect vs. Skills

When we start thinking about emergencies and how to handle them, we can split the potential crises into two general groups. First are the ones that we can visualize and deal with intellectually; they take no particular level of skill to handle. For example, we deal with an alternator failure by following the appropriate procedure to get it back on line or, if that doesn’t work, by deciding on what equipment we can do without and shut it down to shed electrical load. Then we need to come up with a suitable airport on which to land.

Other type of emergencies require us to attain and—this is the big one—maintain a certain level of skill. Those are the ones we have to practice in the airplane (or simulator), usually with an instructor. Sitting on the couch and visualizing the engine failure on takeoff at 300 feet agl or spatial disorientation on punching into low clouds is a great idea, and it will help if it happens for real, but it’s also necessary to go out and practice them with some frequency. The intensity with which the nose has to be shoved down, against all of those urges to pull it up and fighting those senses that tell you the instruments are wrong are things that just plain have to be experienced.

We want to practice this stuff realistically and regularly, because we know in our heart of hearts that our IFR skill level atrophies horribly fast. But, practice is expensive; so how do we find and maintain an acceptable level of competence for ourselves without going broke?

Systems Knowledge Is King

I suggest that we schedule a session of dual every six months—that we set up a standing appointment and keep it. We’re going to fly anyway, so budget an extra hundred bucks or so every six months for that session. However, before we go, let’s pull out that list of emergencies we created and go over it. Alone. Where we won’t be interrupted and where we can give ourselves enough time to visualize what is happening and what we would do about it. Then go through the emergency section in the POH and visualize each problem and solution as if it were happening when we’re in the clag. Where is the circuit breaker we will pull? Where exactly is the fuel selector for that airplane and which way does it turn to the “off” position and do we have to move a tab or push down or do something else to get it to “off?”

Go through the memory items on the you-gotta-do-it-right-now checklists. You know, the stuff that we have to commit to memory, because we won’t have time to pull out the checklist. For most emergencies, once the memory items are completed there is enough time to pull out the checklist and take care of the other stuff.

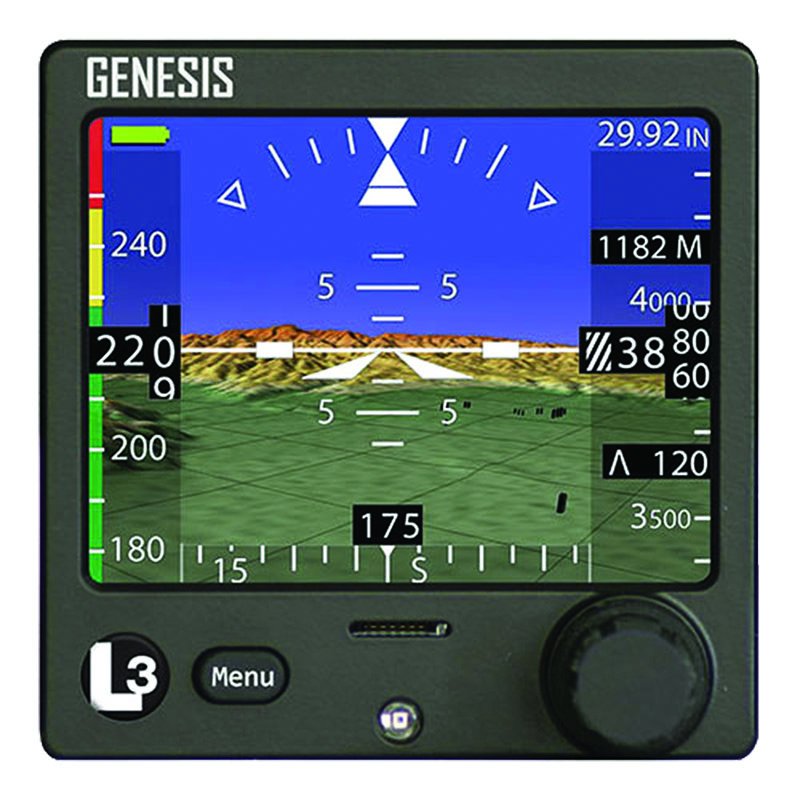

For those of us who fly more than one type of airplane or bounce between types of panels and avionics, we have to find some way to make sure we know the critical differences in emergency procedures between them. There are some things that are pretty generic: For most airplanes in the event of an engine fire, an immediate action item is to shut off the fuel supply to the engine. After that, things may vary; most airplanes call for the cabin air and heater vents to be closed, but not all. In some airplanes the cabin air vents are to be opened in the event of some types of fire. What exactly is the procedure in the airplane you are going to fly today? Finally, along with using our systems knowledge to overcome failures, how about a whole ‘nuther system? Consider a backup alternator, or a dedicated backup gyro like the ones above.

Practice On Your Own

Before we go for the session with an instructor, we can also notice that there are items on the emergency checklists that require some level of skill, but that we could probably practice on our own or with a safety pilot, saving us money during that session of dual.

As pilots, we should know ourselves; and if we are willing to be honest with ourselves we can make an informed selection of those emergencies that we should be practicing in the airplane (or simulator). By and large they are going to be the ones that require skill maintenance, or the ones that frighten us—a realistic concern. So, to keep the cost of that recurrent training down, it might be a good idea to talk over the syllabus we are going to follow with the CFI before the dual session. We will probably have a list of emergencies that is long enough that we can’t do them all in one recurrent session and still remain financially solvent. As a result, if we practice half of them each six months it’s a heck of lot better than omitting some completely.

Oh, yeah, another technique for getting ready for that review session is to go out and sit in the airplane when no one else is scheduled to fly it. Use the emergency checklist and walk through each of the emergencies, reaching for and physically moving the controls to help remind our bodies what they are going to do when it happens.

Make It Count

We can work with our CFI to set up a true learning experience. We can do the flight when the weather is marginal, so that we get a chance to see what it’s like when there’s a good chance we’ll have to miss an approach, but we have that safety valve there in the right seat to help us experience what it’s like for real. We can fly a real circle to land in crummy visibility, close in so we don’t lose sight of the runway, and obtain a visceral understanding why single-pilot circle-to-land approaches may not be for us.

While we hope we are smart enough to cancel flights in low IFR weather or land before it gets awful, if we do screw up someday and have to divert when it’s for real, we’ve got a better chance of surviving than if we’re doing it all for the first time. Afterwards, the discussion we have with the CFI about decision-making in instrument weather will be more informed.

After one or two of those six-month sessions, you may just improve your chances of living to enjoy the nursing home. Once you get there, give me a call, I’m hoping I’m still around so I can come over and we’ll see who can tell the more boring story of our flying days.

Rick Durden is a practicing aviation attorney and type-rated ATP/CFI with more than 7500 hours.