A turboprop-conversion Beech Bonanza crashed during an attempted night approach in IMC, killing the pilot and two passengers. Forget for a moment that the NTSB’s investigation revealed the pilot was using unapproved medications and was not even instrument-rated. Lost in the details of the accident report is that even if the pilot was IFR-rated and current, he should not have been flying that approach. Yet controllers cleared him to fly it anyway. Why should even a qualified pilot not have flown the approach? Because it was after dark, and the approach was marked “NA at night.”

As pilot in command, it’s your responsibility to determine whether an approach is authorized. It’s your job to avoid asking for an unauthorized approach, and to refuse a clearance if it includes a procedure that’s not authorized. The FAA’s guidance to controllers is to clear you for any procedure you request as long as there is no conflict with other IFR aircraft.

So what types of procedure are “not authorized” under certain conditions? How do you determine if a procedure is not authorized? What are the rules about requesting and clearing a pilot for an unauthorized approach? How can you, as a fully rated and current pilot, avoid flying a procedure that you’re not authorized to fly?

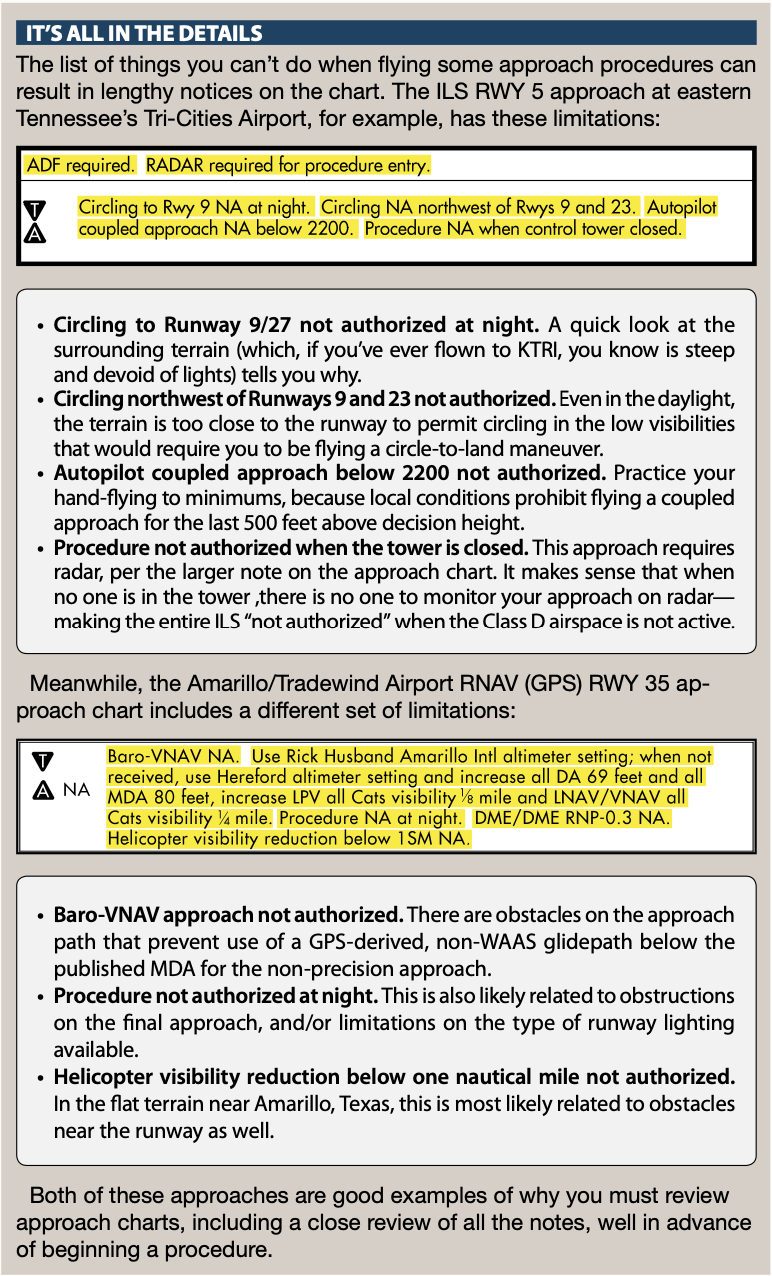

THE FINE PRINT

There is no specific symbol on approach charts to alert you that the procedure may not be authorized like there is for nonstandard takeoff or alternate minimums. You’ve got to read the notes at the top of the chart and look for the notation “NA.” Here are some limitations you may find noted on the chart for an instrument approach.

NA at Night: Some approaches are not authorized at night. The runway may not have sufficient lighting to meet requirements to be flown at night. More commonly, unlighted obstacles in the vicinity may be tall enough to limit the procedure to daylight use only—you’ll have no way to see and avoid those obstacles during any visual maneuvering that accompanies the approach. This notation is sometimes buried within other notes, so look closely. An example of how this limitation may be buried in the procedure’s notes can be found in the second example, for the Amarillo/Tradewind Airport RNAV (GPS) RWY 35, of the sidebar at right.

Circling NA: If there are terrain or obstacles near the airport, straight-in approaches may be authorized but circle-to-land maneuvering may not. A variation on this theme is when an obstacle exists on one side of the airport but not others, and circling is not authorized if it takes the airplane near that obstacle. In this case, you will see a note that says something like “Circling NA northwest” if any circling maneuver northwest of the airport puts it in conflict with the obstacle. The first example in the sidebar at right shows how this limitation is presented for an approach at Tennessee’s Tri Cities Airport.

Circling NA at Night: It may be that obstacles or terrain permit circling in daylight conditions (even in poor weather that requires a circle-to-land maneuver), but the obstruction is not lighted so attempting the circling maneuver at night is hazardous. In this case, a note such as “Circling NA at night” provides you this warning. This type of limitation also is depicted in the first example in the sidebar at right. Sometimes circling at night is permitted but only if a visual glideslope indicator is operating. If that visual glidepath is inoperative, then circling will be “NA.” Note that the limitations on night circling to a specific runway may be different for other approaches into the same airport—so read the notes!

Landing NA at night: Even when there is no specific limitation on night circling, you may not have the choice of all available runways during a circling approach at night. In the case of Sedalia, Missouri, for example, you can circle at night if you want to, but you cannot land on Runway 5/23 at night. See the sidebar on page 15 for an example.

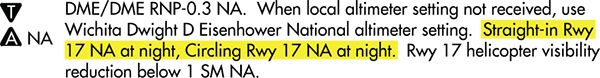

Straight-In minimums NA at night: At first glance this may seem odd. It sounds like it means straight-in procedures are not authorized, but circling maneuvers are. That seems backward. What the “Straight-in minimums NA at night” notation is really saying, however, is that you must use the circling minimum value to define MDA, DH or DA even if you’re flying a straight-in approach—a straight-in procedure is authorized, but you must use the higher circling minimums. This is usually because the runway has limited lighting that does not completely prevent use of the procedure at night, but requires you to be more conservative about flying it after dark.

The FAA directly advises pilots of our responsibility to adhere to the notations on approach charts in Section 5 of the Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM):

Section 5. Pilot/Controller Roles and Responsibilities

5-5-4. Instrument Approach

a. Pilot.

1. Be aware that the controller issues clearance for approach based only on known traffic.

2. Follows the procedure as shown on the IAP, including all restrictive notations, such as:

(a) Procedure not authorized at night;

(b) Approach not authorized when local area altimeter not available;

(c) Procedure not authorized when control tower not in operation;

(d) Procedure not authorized when glide slope not used;

(e) Straight-in minimums not authorized at night; etc.

(f) Radar required; or

(g) The circling minimums published on the instrument approach chart provide adequate obstruction clearance and pilots should not descend below the circling altitude until the aircraft is in a position to make final descent for landing. Sound judgment and knowledge of the pilot’s and the aircraft’s capabilities are the criteria for determining the exact maneuver in each instance since airport design and the aircraft position, altitude and airspeed must all be considered.

RNAV/VNAV LIMITATIONS

So far, the limitations I’ve outlined involve terrain or structures, or unlighted obstacles, that penetrate protected areas. They may apply no matter what navigation aid is used for the approach. But some RNAV systems require entering barometric information (the local altimeter setting) to “compute and present a ertical guidance path to the pilot. The specified vertical path is computed as a geometric path, typically computed between two waypoints or an angle based computation from a single waypoint,” according to the FAA’s Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM). This is known as a Baro-VNAV system, and WAAS-enhanced GPS navigators approved for instrument approaches generally don’t use it.

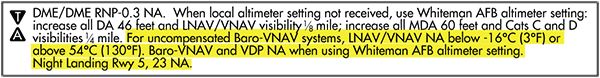

When using Baro-VNAV guidance, pilots should check for any temperature limitations which may result in approach restrictions. The AIM tells us: “A minimum and maximum temperature limitation is published on procedures which authorize Baro-VNAV operation. These temperatures represent the airport temperature above or below which Baro-VNAV is not authorized to LNAV/VNAV minimums.” The sidebar at upper right presents an example of how this limitation is depicted for the RNAV (GPS) RWY 18 procedure at Sedalia, Missouri, (KDMO).

Again, according to the AIM: “Many systems which apply Baro-VNAV temperature compensation only correct for cold temperature. In this case, the high temperature limitation still applies. Also, temperature compensation may require activation by maintenance personnel during installation in order to be functional, even though the system has the feature. Some systems may have a temperature correction capability, but correct the Baro-altimeter all the time, rather than just on the final, which would create conflicts with other aircraft if the feature were activated. Pilots should be aware of compensation capabilities of the system prior to disregarding the temperature limitations.”

The advent of the wide-area augmentation system (WAAS) means GPS navigators so equipped need not worry about Baro-VNAV corrections. “Temperature limitations do not apply to flying the LNAV/VNAV line of minima using approach certified WAAS receivers when LPV or LNAV/VNAV are annunciated to be available,” says the AIM.

In other words, if you’re flying a GPS approach using a non-WAAS approach-certified GPS, watch for limitations on the use of the advisory glidepath in very hot or very cold conditions. If you’re using a WAAS-enhanced GPS and/or the temperatures are not extreme, you’ll quickly dismiss this warning if and when you see it.

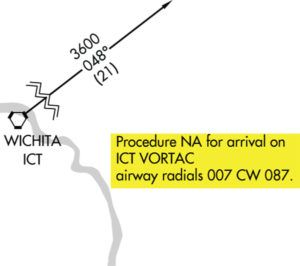

Two more examples of how what we may want to do isn’t authorized come from the RNAV (GPS) RWY 17 procedure at the Lloyd Stearman Field (1K1) in Benton, Kansas. Straight-in minimums to Runway 17 are NA at night, and circling to the same runway is NA at night. At first glance it looks like the procedure is NA at night at all, and you might wonder why it’s not labeled as such. But there’s no note saying you can’t circle to Runway 35.

Depending on where you’re coming from, the procedure may not be authorized at all. A note in the plan view states the procedure is NA when arriving via the ICT Vortac on radials 007 clockwise to 087. That means there’s no published transition from ICT to an initial approach fix (IAF). There are two easy solutions to this dilemma, however. The most common one would be to request vectors from ATC to one of the three IAFs. The other would be to not proceed as far as ICT, since arriving on many of the NA’d radials would take you over or through the approach’s standard-T configuration. This is just one more example of why planning—and reading all the notes—is key. —J.B.

WHY WON’T ATC PROTECT ME?

Controllers won’t prevent you from trying to fly an unauthorized approach. According to the FAA’s guidance to controllers in JO 7110.65Y—Air Traffic Control, the so-called controller’s “bible,” “Approach clearances are issued based on known traffic. The receipt of an approach clearance does not relieve the pilot of his/her responsibility to comply with applicable [FARs] and the notations on instrument approach charts which levy on the pilot the responsibility to comply with or act on an instruction; e.g., ‘Straight-in minima not authorized at night,’ ‘Procedure not authorized when glideslope/ glidepath not used,’ ‘Use of procedure limited to aircraft authorized to use airport,’ or ‘Procedure not authorized at night’” (emphases added).

While it’s true that controllers often offer services beyond basic traffic advisories, especially in emergency situations, their first and most-constant duty is to separate traffic. Put another way, they are not responsible for protecting pilots from themselves. It’s always your responsibility to research and adhere to any restrictions on approaches and landings—including knowing and making the call as to when a procedure is not authorized. It’s all part of the awesome pilot-in-command responsibility you accept when you exercise the amazing freedom of flight.

Please note also that the foregoing is not an all-inclusive list of the types of limitations that may be imposed on terminal procedures resulting in their not being authorized under certain conditions, including time of day, observed weather, type of operation or airborne equipment. Read the notes completely as you brief for the approach. Remember, your success is in the details.

The RNAV (GPS) RWY 18 approach to Sedalia, Missouri (KDMO) shows a Baro-VNAV temperature limitation. For non-WAAS approach-certified GPS, the LNAV/VNAV decision altitude is normally 1155 MSL. When the ambient temperature is below -16 degrees C (+3 degrees F) or above 54 degrees C (130 degrees F), the glidepath may only be used down to the MDA of 1260 feet msl. If the airport is not in sight at the MDA, you must miss the approach even if the GPS shows VNAV is available.

I served at nearby Whiteman Air Force Base and my first flight instructor job was at Sedalia—it’s not likely to get above 130 degrees F, but there are many times that the temperature gets below 3 degrees F.