Instrument-rated pilots are familiar with visual approaches, which allow them to fly to and land at an airport in good weather without executing what might be a time- and fuel-consuming published procedure. Air traffic control also recognizes other visual clearances, which can allow pilots to shortcut one or another procedure that might otherwise increase risk or not be possible under various conditions.

Perhaps the most well-known is a clearance to maintain “VFR on top” of a cloud deck—or between two of them. A VFR climb also may be approved, or simply an IFR climb to VFR conditions. Each of these clearances differs from the others and comes with its own rules, operational considerations and drawbacks, however. Because there’s no free lunch. Let’s run through them.

VFR-ON-TOP CLEARANCES

The FAA’s ATC bible, Order 7110.65Z, Air Traffic Control, (ATC order) defines “VFR-on-top” as “ATC authorization for an IFR aircraft to operate in VFR conditions at any appropriate VFR altitude,” which is straightforward enough. It allows pilots to fly in VFR conditions at VFR altitudes but on an IFR flight plan. The FAA’s Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM) says it a bit differently, and sheds additional light: “A pilot on an IFR flight plan operating in VFR weather conditions, may request VFR-on-top in lieu of an assigned altitude. This permits a pilot to select an altitude or flight level of their choice (subject to any ATC restrictions.)”

It’s important to note that “ATC will not authorize VFR or VFR-on-top operations in Class A airspace,” according to the AIM, so presence of the “flight level” phrase in its definition is curious. It’s also important to note a pilot must request a VFR-on-top clearance

There’s more fine print. For example, we’ve already touched on the VFR altitude requirement, but a pilot operating IFR with a VFR-on-top clearance also must comply with the “VFR visibility and distance from cloud criteria” in FAR 91.155 (Basic VFR Weather Minimums). Notably, those criteria in Class C, D and E airspace (below 10,000 feet msl) require three statute miles of visibility and remaining 1000 feet above clouds. Yet VFR-on-top may only buy us 500 feet above our IFR altitude.

Pilots accept greater responsibility when operating IFR with a VFR-on-top clearance. According to the ATC order, “the pilot is responsible to fly at an appropriate VFR altitude, comply with VFR visibility and distance from cloud criteria, and to be vigilant so as to see and avoid other aircraft.” Put another way, we give up the ability to enter IMC at will while our vigilance to see and avoid other aircraft exists anytime we’re in visual conditions, anyway, whether operating IFR or VFR.

We must also comply with applicable IFR rules, like “minimum IFR altitudes, position reporting, radio communications, course to be flown, adherence to ATC clearance, etc.” according to the AIM. Also, the pilot gives up the benefit of IFR separation. The ATC order states, “Although IFR separation is not applied, controllers must continue to provide traffic advisories and safety alerts, and apply merging target procedures to aircraft operating VFR-on-top.” In other words, it’s rather like VFR flight following, except—as we read that language—ATC must give traffic advisories instead of provide them as workload permits.

It’s also important to note that a VFR-on-top clearance doesn’t restrict pilots to operating only above clouds. The AIM again: “ATC authorization to ‘maintain VFR-on-top’ is not intended to restrict pilots so that they must operate only above an obscuring meteorological formation (layer). Instead, it permits operation above, below, between layers, or in areas where there is no meteorological obscuration.” (italics in original)

WHY WOULD I WANT TO DO THIS?

Okaaaay. Why would I want to do this? All it does is allow me to operate at a VFR altitude (plus 500 feet of the IFR altitude) and remain in VFR conditions. Typically, I can enjoy the same VFR conditions without the clearance, remain at an IFR altitude and not be “that guy” to the controller. The extra 500 feet rarely buys anything and if I can maintain VFR 500 feet above the associated IFR altitude but not at it, I can’t legally accept the VFR-on-top clearance in the first place.

The VFR-on-top clearance might buy me some bobbing and weaving to remain in VMC, but not wholesale deviations or route changes. The kinds of weather deviations that might come in handy I usually can get from ATC anyway.

I’m also not going to get a VFR-on-top clearance through an active military operations area (MOA), unless it’s been coordinated with all pertinent agencies, which also is required without the VFR component, since you’re still IFR. In the MOAs with which I’m familiar, it’s unlikely to get cleared through them IFR when they’re active.

A VFR-on-top clearance isn’t even valuable when passing through Class C or D airspace at a complying altitude and the official weather observation says it’s IMC on the surface, since you’re already IFR. If VFR, a Special VFR clearance will accomplish the same thing. I can also see where a VFR-on-top clearance might be useful to a flight of multiple aircraft who want to maneuver above a cloud deck, for example, when conducting a photo or formation-flying mission. A VFR-on-top clearance would allow them to retain the IFR clearances they obtained to get through the clouds and keep them “in the system” so they can get back down in short order. See the image and caption above for some additional details.

I can also see where a VFR-on-top clearance would come in handy for training when there’s a low cloud deck but clear skies above. Depart IFR, climb to VFR, get the clearance, and maneuver more or less at will, or as ATC allows. And I can see where it would save time and fuel in certain situations, like relieving ATC of imposing IFR separation when, for example, practicing IFR procedures in VFR conditions above a cloud deck.

Finally, I also can see where a pilot might want to climb out of a cloud deck to get to VFR and relieve themselves of having to fly on the gauges for long distances, or to accommodate passengers who don’t want to look at the inside of a cloud all day. I also can see where it might be used to avoid known icing conditions, but I would still have questions as to whether it’s valuable to operate on a VFR-on-top clearance instead of just requesting a different IFR altitude in these situations.

CLIMB IFR TO VFR

One situation where something approaching a VFR-on-top clearance would come in handy involves an IFR airport under a cloud deck. The idea is to take off with the IFR clearance and then climb through the cloud deck until reaching VFR conditions, and then canceling IFR. This is fairly common, and typically is a good plan when instrument conditions at the departure airport are not widespread but the en route and destination weather are VFR and pretty much guaranteed to stay that way.

The ATC order lays it out to controllers like this: “You may clear an aircraft to climb through clouds, smoke, haze, or other meteorological formations and then to maintain “VFR-on-top” if the following conditions are met:

1. The pilot requests the clearance.

2. You inform the pilot of the reported height of the tops of the meteorological formation, or

3. You inform the pilot that no top report is available.

4. When necessary, you ensure separation from all other traffic for which you have separation responsibility by issuing an alternative clearance.” Once reaching VFR conditions, the flight can obtain a VFR-on-top clearance or, more likely, just cancel IFR and motor on.

The fine print here is that the IFR takeoff may require flying a departure procedure, and you’ll certainly will be subject to any traffic-related delays as well as appropriate routing. That may or may not make the “IFR climb to VFR-on-top” type of plan worthwhile.

All of that having been said, it again strikes me as much ado about nothing, penny-wise and pound-foolish, and involving cutting off your nose to spite your face, to throw out some aviation sayings. Unless you have some sort of special mission or aircraft performance issue where IFR along the route isn’t advised for some reason, why not plan and fly the flight under IFR from start to finish? More about this in a moment.

There’s another phrase out there involving “VFR” and “top”: “VFR over the top.” This essentially refers to departing an airport in good VFR, encountering an undercast while en route, then landing at your destination, another airport with VFR weather. As such, this phrase more accurately describes an operation instead of a clearance, much less an IFR clearance. Presuming the weather allows you to maintain VFR on top of the undercast—or even between layers—it’s just another VFR flight. The only real gotcha is if the airplane suffers a mechanical problem and you’re forced down into the instrument conditions. Without an instrument rating, that can be a problem, which probably is why the operation has its own name.

VFR CLIMB IN LIEU OF A DP

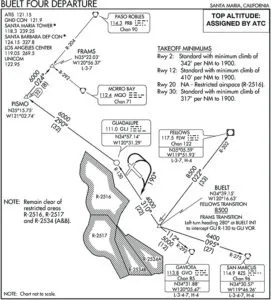

Another way to combine VFR with an IFR clearance is when a departure procedure would take you far out of your way and/or aircraft performance won’t allow meeting the DP’s required climb gradient. Typically, this situation arises in hilly terrain and, as a consequence, you need to ensure you’ll be able to climb VFR to an appropriate IFR altitude. The graphics on the opposite page highlight a situation where this might be preferable to flying the DP.

Another way to skin this cat would be to work out with ATC that you’ll climb VFR over the airport to the appropriate altitude—either 1900 feet msl or 4000, whichever ATC allows—then join the DP’s routing. You still have to cross BUELT at 8500 feet, however, and you have less than 20 miles to do it, so maybe climbing over the airport to 4000 feet isn’t even enough.

A VFR climb to join a segment of the IFR en route system also can come in handy at remote airports when slower IFR traffic in front of you means ATC will hold you on the ground until the earlier departure reaches a fix or altitude at which separation can be assured. This is akin to picking up the IFR clearance airborne, except ATC is working with you to keep the flow going and workaround the slower traffic.

WHY NOT JUST KEEP THE IFR?

As I noted earlier, VFR climbs and/or cruising on a VFR-on-top clearance can make sense in some limited circumstances. But for the most part, it strikes me as a kind of gimmick to get out of having to fly IFR like the rest of us. Speaking for myself, I take great comfort in hearing the words “radar contact” when departing IFR and know from experience that once I give it up, I may have trouble getting it back.

A VFR-on-top clearance can make sense if you absolutely, positively don’t want to fly in the clouds for any length of time. But the solution in my mind would be to simply ask for an IFR altitude that’s in visual conditions. Put another way, maybe you shouldn’t be flying IFR if you’re afraid of being in clouds and/or just don’t want to. By contrast, I’ll absolutely file IFR for almost any trip out of the local area. Maybe I’m weird, lazy and like to be coddled, but I’ll take the warm embrace of an IFR clearance over the go-it-alone nature of a VFR cross-country any day.

And, yes, I’ve operated on a few VFR-on-top clearances over the years, albeit not recently. I initially thought doing so might afford some benefits in busy airspace, but it doesn’t, since routing and other variables remains up to ATC, and the controllers’ “put them together to keep them apart” mentality makes it fruitless to try using VFR-on-top to slide one over on them.

Jeb Burnside is this magazine’s editor-in-chief. He’s an airline transport pilot who owns a Beechcraft Debonair, plus the expensive half of an Aeronca L-16B/7CCM Champ.