One of the instrument rating’s dirty little secrets that no one tells you about until it’s too late is the amount of recurrent training you need to legally fly IFR after the checkride. The details—along with options and potential loopholes—are in FAR 61.57, Recent flight experience: Pilot in command, portions of which we all know by heart. If you don’t regularly fly instruments and log approaches in either simulated or actual conditions, your currency soon will lapse and, eventually, the only way to get it back is via an instrument proficiency check (IPC). After our currency lapses, most of us will need some brush-up to even get through the IPC, which can mean multiple flights, and greater expenditures of time and money.

When pilots think about practicing instrument approaches, we often get hung up on needing a safety pilot before using a view-limiting device. In the middle, hopefully, of a pandemic, finding a qualified person to ride shotgun can be even more challenging than it was before, or will be again. But there are ways to simulate instrument conditions in an actual airplane that minimize the need for a safety pilot. No; there’s no app that eliminates the need for a safety pilot, but there are many things we can do in our everyday flying or in dedicated training that can make safety pilots relatively rare.

Once we accept the dichotomy between flying the airplane and configuring its avionics, it’s a very small leap to embrace using non-approved simulators for training purposes. None of it is loggable toward meeting the recent-experience requirements, but the time it can save when flying a real airplane easily is worth the minimal investment. In fact, even if your only computer is a laptop and the only input device you have is a keyboard, it can still provide some worthwhile training.

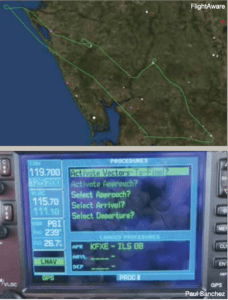

Software packages like X-Plane (pictured) and Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020 offer some relatively inexpensive training opportunities. Depending on what you fly, you probably can find a sim that emulates it. Even if you can’t, there’s always a steam-gauge Skyhawk (above) or something similar with which you likely have experience. Regardless, the idea here isn’t to reproduce the exact airplane you fly but to practice the procedures, configuration changes and avionics management that makes IFR in today’s environment both easier and more challenging. Typically, you also can practice local approach procedures that you’ll fly for-real in the airplane. That’s gotta help you get through your next IPC.

TWO MAJOR COMPONENTS

It used to be that instrument flying was all about using a control yoke or stick as poorly designed flippers and playing pinball with the flight instruments. You got a replay when you broke out of an NDB approach in something approximating a position from which you could make a “normal” landing. (If you didn’t get a replay, you fed more quarters into the machine.) Some would argue the pinball analogy is even more true today, with all the newfangled video screens and moving maps.

While modern avionics have transformed how we obtain and maintain situational awareness in the cockpit, and offer much greater accuracy and repeatability than ever before, they also have burdened us with learning new skills. Understanding and managing the various operating modes and capabilities new equipment offers directly competes with basic aircraft control for the limited number of CPU cycles our feeble human brains can offer. Splitting apart the tasks of flying the airplane and programming the magic can simplify how we learn and practice instrument approaches.

After a recent practice ILS and missed approach at Class C Regional, my instructor and I motored off to the published hold, swooped through the teardrop entry and joined the inbound leg. I used a loop or two in the hold to set up for the next approach, an RNAV procedure offering LPV minima, to a nearby nontowered field. After reconfiguring, I told George to fly the heading to the initial approach fix and off we went. About halfway there, I asked aloud why the annunicators were still showing the navigator was set up for a VOR/LOC procedure when the active procedure was an RNAV approach.

My right-seated instructor responded with the equivalent of, “You didn’t press the OBS button, dummy, the one that takes the box out of ILS mode.” She was right, and that episode highlights how there is more to an instrument approach than “simply” keeping the needles centered. We need to fly the airplane solely by reference to the instruments, but we also need to manage the avionics.

Again, breaking the overall problem into (at least) two separate tasks facilitates the learning process. Once we do that, practicing approaches becomes something we can do almost anywhere. For some of the how and why, see the sidebars above and below.

As emphasized in this article’s main text, practicing approaches is only half about flying the airplane; you still have to configure the avionics. Simulation tools available from the manufacturers often can be used to learn not only the basics, but advanced operations, also, along with practicing for tomorrow’s checkride.

At right are screenshots from Garmin’s GPS Trainer Aviation App, which is designed for Apple iPads and “realistically simulates the capabilities and user interface of our GPS 175, GNC 355 and GNX™ 375 navigators,” according to the company. Garmin also offers training apps for its GTN and TXi product lines. Other avionics manufacturers, including Avidyne, offer similar training aids.

GOING SOLO

Of course, there’s nothing that prevents us from flying approaches in VMC without a safety pilot—we just can’t wear a hood or other view-limiting device while we do it. As such, we can’t log simulated instrument time and it doesn’t count toward the six we need every six months. Another downside when in visual conditions is the need to keep our own eyes peeled to watch for traffic.

But as we’ve discussed, practicing approaches isn’t always about simulating instruments. For one, we still have to configure the avionics. For another, if we do it with ATC assistance, or at a towered airport, we get much more of the true flavor of flying instruments out of the exercise. A third reason to practice approaches in VMC is that we’ll still need to nail the pitch and power settings we fly on the real ones and manage the airplane’s configuration, among other tasks. Nailing the airspeeds and procedures can be just as important as keeping the shiny side up, especially if there’s a thick layer of rust on our skills.

Presuming your currency hasn’t expired, you also can go out on IMC days by yourself. Pick a day with barely instrument conditions—an 800-foot overcast, for example, with good visibility underneath and no thunderstorms—and you’re getting the best of what practicing approaches can offer. There’s likely a towered airport with an approach control nearby, and while you may not be endearing yourself to ATC by flying multiple approaches amid the other traffic, it’s good experience and training, and it’s loggable.

There are some caveats, of course. First, you’ll need to file a for-real IFR flight plan. Presuming you’re based at the desired airport, file a flight plan from it and to it, with “multiple practice approaches” in the remarks block. Don’t forget to file an alternate. Clearance delivery might ask a few questions, but unless there are some kind of flow control measures imposed, they’ll send you off into what I call the “radar pattern,” a rectangular flight path not unlike a traffic pattern, but with longer legs and the occasional delaying or spacing vector for other traffic. You’ll get real-world IFR service and there’s not a more realistic way to practice and perfect your instrument-flying skills.

Although no plan survives contact with the enemy, it’s just as important to have one when practicing approaches as it is when motoring off on a business trip. The plan could be as simple as getting into the radar pattern at your home airport and going around the circuit for an hour or as complicated as a round-robin to three different airports and types of approaches, as depicted in the ground track at right.

When flying with a safety pilot, of particular interest will be what, if anything, you expect of the right-seater beyond looking for traffic. Regardless, you want to have something in the way of a plan for what you’ll do at the end of each approach, where and for how long you’ll plan to hold when flying a miss, and what alternatives exist if you can’t check all these boxes.

In other words, treat this just like a real flight, which it is, if for no other reason than ATC will want to know in advance what you’re going to do.

DON’T FLY THE VISUAL

Another dirty little secret about the instrument rating? It’s relatively rare to actually fly an approach procedure in the real world. Why? Because unless you’re based someplace like the California Redwood Coast-Humboldt County Airport, in Arcata/Eureka, California, which generally is acknowledged as one of the foggiest airports in the U.S., the weather likely will cooperate and allow you to get in on a visual approach. Even when we need to log a real one or three, it’s too easy to expedite our arrival and opt for the visual. You don’t have to.

Instead of defaulting to the visual, plan ahead and fly a published procedure. The ATIS or automated weather will advertise the runway in use or the one most favored by the winds. Tell the local approach controller as soon as you can which published approach you’d like to that runway, and off you go. When it’s really busy, or your destination is Class B International at rush hour, asking for the full approach procedure in lieu of a visual isn’t likely to endear you to anyone, again, so use this option with discretion. But if the timing, weather and traffic are right, dive right in, especially if the procedure has an odd feature or two. And remember: Controllers often need practice, also.

There’s another option to practicing approaches and procedures in the airplane or at home: flying them on an approved training device, or simulator. It’s likely some flight school near you has one and it almost has to be cheaper than burning fuel, even when factoring in an instructor’s time. If you haven’t used the one available, there will be a learning curve, and it’s unlikely to simulate the specific airplane and panel you regularly fly. So what? You might learn a few things along the way as you add to the number of approaches you’ve flown recently. Isn’t that what practicing approaches is all about?

GRADING YOURSELF

Throughout all this, let’s not forget that an objective of practicing approaches is to get proficient at flying them, not to just to log the minimum number every six months and move on. Too often, we shoot the approach, make a mental note that we made some mistakes and tackle the next shiny object without taking any real steps to correct our errors. Instead, adopting some performance standards will improve your practice sessions and your skills. Especially if you’re really rusty, a place to start is the instrument rating airman certification standards for your certificate/rating.

The instrument rating ACS allows up to a ¾-scale deflection and plus/minus 10 knots, tolerances which are tightened to ¼-scale and five knots for an ATP. You should be able to do at least that well after some practice, especially if you’re flying the same approach repeatedly. The same is true for other tolerances, like speed, altitude and heading. An instructor-friend of mine is fond of pointing out that if you can maintain altitude within 100 feet, you probably can do it to 50 feet, also.

Be honest with yourself. If that last approach would have you breaking out in the next county over, don’t rationalize away the problem. Once you’ve landed or are back in cruise flight after the miss, take a moment to analyze what you did wrong. If you don’t know, maybe some dual is in your future.

Keeping your instrument rating current can be a major hassle, depending on how much you fly, and where. But practicing approaches is a fact of the instrument pilot’s life. Make it a worthwhile experience.

I’m as guilty as the next guy or gal when it comes to using the autopilot to fly approaches. My mantra is to practice like I’ll fly, and Otto is there for a reason. Each autopilot and installation has its own quirks, of course, and stumbling around in the clag with 30 minutes remaining before bingo fuel is not a good time to forget yours won’t capture the glideslope from above. Yes, the procedures involved in configuring the autopilot and ensuring it captures the navigation signals is part of the process, one we should practice and understand. But it may not always be available to you, for reasons.

Meanwhile, Otto isn’t the only thing in your panel that can fail. Steam-gauge airplanes can lose their vacuum system and avionics can pop a circuit breaker or suffer a failed attitude/heading reference system. Simulating vacuum system failure is rather simple while doing the same with an EFIS is a bit more complicated. Tough. There’s always the chance your next for-real IFR flight won’t go as planned, or your EFB will take the day off. It pays to practice for the unexpected.

Jeb Burnside is this magazine’s editor-in-chief. He’s an airline transport pilot who owns a Beechcraft Debonair, plus the expensive half of an Aeronca 7CCM Champ.