One of the many avionics advances in recent years is the autopilot. Not that long ago, the typical personal airplane didn’t have a working autopilot—it might have been in the panel, but it was rare for it to work, much less as well as a modern one does. For one thing, altitude hold or preselect was an unavailable feature. For another, even when it worked, you probably were resigned to heading mode, if for no other reason than there was no long-range navaid available, and they certainly didn’t fly the procedure turn for you. So we hand-flew everywhere, and we got pretty good at it.

The good news is that digital technology has replaced the analog workings. The better news is the new ones are much more reliable. They’re also much more capable, seamlessly tracking a GPS navigator through procedure turns and flying flawless glide paths to the runway. Devices like the Garmin GFC 600, pictured below, also offer “big airplane” features like a flight director, vertical navigation, airspeed hold and more. Also, modern autopilots many offer a “get out of jail free” button to automagically level the airplane if you can’t. The bad news, of course, is we’re now dependent on them, especially for IFR.

Good IFR Platform?

The aviation magazines of a few decades ago often discussed whether a given new-design personal airplane was “a good IFR platform.” Was the airplane inherently stable in pitch and/or roll? Did its panel offer enough space to install a couple of KX-170s, a DME, an ADF and a non-working autopilot? Did it have sufficient fuel capacity to fly, say, 500 miles, shoot an approach, miss it, divert to an alternate and still have 45 minutes of gas? Seeing that phrase in a new-airplane review these days is rare, if for no other reason than a traveling airplane—which we define as something with at least 180 hp—typically comes from the factory with a full, well-integrated panel, ready for cross-country work.

But the general question remains, and the answer basically hinges on whether the pilot, that’s you, is fully prepared to fly the airplane in what’s come to be known as “hard” IFR, when conditions pretty much are IMC from takeoff to breaking out on the approach at the destination. By hand.

Getting To Carnegie Hall

We’ll go out on a fairly stout limb and suggest that flying a three- or four-hour jaunt without an autopilot is not something the typical instrument pilot does on a regular basis. The corollary is that the same pilot probably isn’t ready to do that, either. So the first decision you need to make is whether you’re “comfortable” flying without the autopilot. Can you manage hand-flying a complicated departure, arrival and approach into a busy airport along with everything else? The only real way to know is if your recent practice and training includes hand-flying for the day when Otto takes personal leave.

Knowing whether you’re up to the task shouldn’t be rocket science. How much instrument time have you logged in the last few months? How much of it was mostly in cruise, with Otto present and performing? Did you depart in VMC and get the visual at your destination? When was the last time you hand-flew a hold or procedure turn?

If the answers to these questions don’t leave you with a warm fuzzy, then the idea of flying your cross-country without an autopilot probably isn’t a good one. It reminds us of the punchline for the old joke about the New York City tourist asking a local how to get to Carnegie Hall: “Practice.”

Two-Phase Practice

Instrument instructors often rightly stress partial-panel work when you’re going for an IPC, but in our experience, at least, they don’t spend much time focusing on whether the failure involves the autopilot. In part, that’s a reflection of their reliability these days. It’s also a reflection of the rarity of actually having to fly a full approach at the destination instead of getting vectors to the airport and a clearance for the visual 15 miles out.

The answer should be obvious: Hand-fly the practice session, engaging the autopilot only when it’s over and you’re returning to home plate. Yes, you’ll be tired, and maybe thankful there’s another pilot aboard. Think about how tired you’ll be after spending three or four hours without Otto.

No, you don’t have to and probably shouldn’t always do an IPC or hood practice without the autopilot. Managing the magic is as much a part of becoming and remaining a good IFR pilot as is hand-flying. But you certainly should mix into your training simulated autopilot failure. And if you really want to get tired, combine failing the autopilot with loss of, say, your panel’s attitude and heading equipment, or the pitot/static system. Balancing your instrument training to ensure you can cope with equipment failures is your responsibility.

Preflighting

There are many autopilots out there, and coming up with a one-size-fits-all preflight inspection is beyond this article’s scope. Your autopilot manufacturer’s manuals will have the final word, but the process goes something like this:

- Turn on the master and avionics bus switches. Give everything three or four minutes to initialize and any gyros to spin up.

- Put the autopilot into test mode and then back to normal. Observe any annunciations.

- Test electric trim by rolling it both ways for a few seconds.

- Engage the flight director and/or heading mode, plus the yaw damper, if any, and altitude hold. Gently deflect the yoke, which should offer steady resistance. Then verify the autopilot and yaw damper, if installed, can be overpowered.

- Verify the autopilot disconnect switch’s function. Reset electric trim for takeoff.

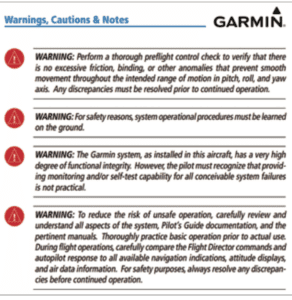

Many modern autopilots perform an internal check when powered up, but as the excerpt above from Garmin’s GFC 600 pilot’s guide notes, “the pilot must recognize that providing monitoring and/or self-test capability for all conceivable system failures is not practical.”

En Route Failures

Knowing the autopilot is unsatisfactory before takeoff is one thing. It’s another to lose Otto once you’re already airborne. Recognizing and reacting to such a failure can easily result in an altitude excursion or missing a turn on a complicated procedure. Catching the failure is key, and that means closely monitoring the airplane’s trajectory: Is it doing what you expect and what you programmed? Is it sluggish and slow to respond? Is one mode or another problematic? Any abnormal annunciations? If you’re paying attention, you can catch any operational problems and minimize their impact sooner rather than later.

It might be embarrassing to admit on the frequency that you have an operational concern regarding autopilot failure, but a bit of embarrassment can forestall something more serious as the flight progresses. As for the rules, FAR 91.187 says navigational, approach, or communication equipment malfunctions “shall” be reported to ATC, but autopilots aren’t mentioned. That said, we wouldn’t hesitate to inform ATC that our autopilot has failed, and that we need gentle, well-planned descents and vectors, and maybe will be flying slower than flight-planned. Lastly, we may want to divert to better weather, and/or turn around and go home. A direct clearance to a good avionics shop is unlikely. Θ