If you’ve had your instrument rating for a few years, filing IFR has probably become second nature for you. Before launching on a cross-country, you naturally pick up the phone to file, even when the weather is CAVU. The idea of not filing an IFR flight plan doesn’t really occur to you. Until, that is, you’re at midpoint on a published departure procedure, wondering why you’re doing all this knob-twisting—and you’re probably not even headed toward your destination. Wouldn’t it be nice to have the privileges of the instrument rating and the freedoms of flying VFR? Well, you often can.

When it comes to clearances, you can cut some deals with ATC most of the time. Of course, as with anything involving the FAA, there are a few strings attached. However, your concerns should not be over any shadows of duplicity, but instead, heeding a few words of caution.

PERKS AND QUIRKS

If you’re an instrument-rated pilot, you already know that being able to file IFR adds a great deal of utility to your airplane. You are no longer restrained when the weather is below basic VFR for the airspace you happen to be in. Also, if you ever need help, it’s already there. You’re guaranteed automatic separation—though only from other IFR aircraft—you get spoon-fed approach vectors and you’re led by the hand through today’s modern-day maze of airspace. Those are the perks.

Some quirks exist, also. Sometimes, you have to sit and wait for a clearance—even idling the engine in the penalty box can quickly get expensive. Circuitous routings, or getting stuck at an altitude with headwinds, turbulence, icing or convective weather also are some of the prices we pay. Still, there are many more good reasons than not to fly in the IFR system. For now, we’ll assume visual meteorological conditions (VMC) prevail and that the controller you’re talking to isn’t distractedly busy. Why VMC? Unless you’re a frequent foul-weather flyer by choice, the fact is that most of the time, that’s really what we fly in.

Regarding one of these quirks, I’m sure that almost every single instrument-rated reader has at least once gotten an assigned initial heading that pointed them almost directly away from their destination, rather than toward it. Aside from filing for a direct routing (hah!), you could ask for a different altitude or a heading change (though this kind of request is usually expected when ice, convective weather or some other problem is involved).

The FAA’s Instrument Flying Handbook, FAA-H-8083-15, is a great reference to learn what you can do (but perhaps not how to do it). What does it say about two frequently confusing operations?

VFR-On-Top

“A pilot on an IFR flight plan, operating in VFR conditions, may request to climb/descend in VFR conditions. When operating in VFR conditions with an ATC authorization to “maintain VFR-On-Top/maintain VFR conditions” pilots on IFR flight plans must:

1. Fly at the appropriate VFR altitude as prescribed in part 91.

2. Comply with the VFR visibility and distance-from-cloud criteria in part 91.

3. Comply with IFR rules applicable to this flight (e.g., minimum IFR altitudes, position reporting, radio communications, course to be flown, adherence to ATC clearance, etc.). VFR-On-Top is not permitted in certain areas, such as Class A airspace.”

VFR Over-The-Top

“VFR Over-The-Top is strictly a VFR operation in which the pilot maintains VFR cloud clearance requirements while operating on top of an undercast layer.

This situation might occur when the departure airport and the destination airport are reporting clear conditions, but a low overcast layer is present in between. The pilot could conduct a VFR departure, fly over the top of the undercast in VFR conditions, and then complete a VFR descent and landing at the destination.

VFR cloud clearance requirements would be maintained at all times, and an IFR clearance would not be required for any part of the flight.” —J.B.

DEPARTURE OPTIONS

The first option to consider is when the weather along your route is actually pretty good, but there’s a low cloud layer over your departure airport. You don’t have to go the whole way IFR, if you don’t want to. In this case, the type of IFR clearance you might want to consider is the climb “to VFR-on-top.”

You can start off with that request in the remarks section of your flight plan, and your IFR clearance ends as soon as you report reaching VFR-on-top. Of course, unless you’re in Class B, you can’t report reaching VFR-on-top until you’re 1000 feet above the cloud layer comprising the ceiling. You’ve got to be proactive and be the one who asks for it. If ATC knows where those tops are, they’ll tell you. They’ll also ask you to report if you haven’t reached VFR by the time you reach a particular altitude. Once you’re on top, ATC will re-clear you to maintain VFR-on-top. After that point, if you want to remain VFR-on-top, there are some things to remember.

But this doesn’t always work. If you’re the first one punching through that day, and the tops just aren’t where area forecasts said they’d be, then what do you do? You might request an amended clearance to some higher altitude, or you might have to contend with a new route, which you’re expected to be able to copy and read back, all while you’re still climbing in the soup. Alternately, if they give you a clearance limit, you might have to hold there for awhile until they figure out a new game plan (i.e., route) for you. If there’s ice where you were hoping to punch through, that’s no help. The upshot with this one is, don’t use it unless you’re fairly sure you’ll leave the clouds behind and below you.

ARRIVALS

As for coming back to earth, two strategies can be useful for avoiding lengthy IFR procedures when you get near your destination. One is fairly safe and benign, while the other one is notoriously tricky. The safer of the two is called, quite simply, a visual approach. Either you or the controller can suggest it. In order to fly the “visual,” not surprisingly, the weather must be VMC (local ceilings must be at least 1000 feet and visibility must be three statute miles or more, e.g., “marginal VFR”).

If you report VFR, ATC likely will trust you, in part since it’s your neck. Either having the airport or preceding traffic in sight will suffice. Warning: In this situation, fudging can prove non-habit forming.

What I mean is that if you get lost in the haze and you don’t say so, you’re asking for trouble. Be aware here that traffic separation (as well as arrival sequencing to the destination runway) is now your job on this type of approach.

The bad boy of these two “sorta IFR” approaches is the contact approach. This one you have to ask for, and you can only get it where there is already a published approach. This clearance makes the most sense for traveling between nearby airports or for pilots intimately familiar with the surrounding area.

Again, it’s up to you to keep ATC informed on what you can (or can’t) see. If in your judgment (or theirs) completing the approach is in doubt, you should accept an alternate clearance. Poor weather, unfamiliar terrain and one mile visibility don’t make a safe mix.

How safe these two approaches actually are for allowing reasonable shortcuts to formal and sometimes lengthy approach procedures, as well as how beneficial it might be to take the easy way up through clouds to VFR on top, all depends on how well you adhere to their limitations. In general, if you’re a compulsive law abider, stay figuratively “on top” of the weather, and maintain your instrument skills, then these procedures represent an operational advantage, allowing you to save a bit of time as well as money.

When operating IFR on a VFR-on-top clearance, you need to comply with two sets of rules. Thankfully, they’re not really all that contradictory.

Altitudes

You can change altitude whenever you want, but you must first inform the controller—just as when VFR and receiving flight following. Also, you’re expected to choose from among only VFR cruising altitudes (i.e., your IFR altitude plus 500 feet) based on your magnetic course. Of course, you must fly no lower than the published MEA or MOCA.

Routing

You must adhere to the assigned route, except that you also must remain clear of restricted areas. You still have to remain on-frequency and communicating with ATC, and you are ultimately responsible to see and avoid all other traffic.

Weather

Note that you can be “on top” even if there’s another layer of clouds above you, such as when you’re between layers, or even when all the clouds are above you. You’ll have to maintain appropriate distances from clouds—in Class B, it’s only “clear of clouds.” Also, you must tell ATC if you can no longer remain in VFR conditions. So, yes, you have freedoms, but the price you pay is that you must adhere to two sets of rules.

STUFF TO WATCH FOR

Of course, there’s no free lunch. You can be happily droning along on your “sort of” IFR clearance when, all of a sudden, things take a turn for the worse.

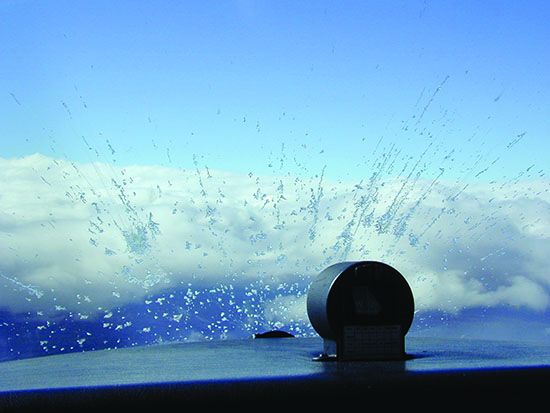

For the folks who usually fly in clear blue skies, clouds represent an approach/avoidance conflict. When I learned to fly, along with the aesthetic satisfaction of communing with clouds and the growing understanding of what they could tell me, I also realized what they could do to me. This is especially relevant for VFR pilots who take the (still quite legal) opportunity to fly above them.

Especially if we’re instrument rated, why might we want to fly VFR above them in the first place? Aside from the initial rapture of surmounting what were formerly your limits to upward vision, you’re probably also going to have: a) better visibility, b) better weather, c) a smoother ride and d) more advance notice of challenging weather ahead. You’re also likely to have less traffic. The higher you go, the more options you have in the event of a power failure, and of course, when you’re literally on top in the daytime, it is quite bright and sunny up there. But unless you have an instrument rating, you’d better also have a guaranteed cloudless climb to and a cloud-free descent from your cruising altitude, beginning at your departure point and continuing to your destination.

When VFR-on-top, keeping the “big” weather picture in mind is more important than ever before. With that in mind, here are some additional things to help improve the safety of your VFR-on-top ops:

• After a cold front passes, except where high terrain is a factor (even in the Appalachians) with building high pressure, when you fly over a layer of scattered clouds, you’re likely to have a smooth ride. (Go underneath though, and it’s likely to be rough as a cob.)

• The eastern side of a high often has descending air, good visibility, scattered clouds, little convection and low tops. On the back side, though, you’re more likely to find moisture, rain or possibly thunderstorms (although not usually in the early morning).

• With a low scattered layer situation, such as is typical of Florida, visual avoidance of rain showers is practical and relatively safe (except with a frontal passage or worse, such as a tropical depression).

• In the southwest, particularly in the high desert country, it’s usually easy to get above low clouds. Turbulence can be nasty though, especially near the Rockies.

Visual Approach

A visual approach is ATC authorization for an IFR aircraft to proceed visually to the airport; it is not an IAP. Also, there is no missed-approach segment. A vector for a visual approach may be initiated by ATC if the reported ceiling at the airport of intended landing is at least 500 feet above the MVA/MIA and the visibility is three statute miles or greater. Pilots must remain clear of the clouds at all times on a visual approach.

Contact Approach

Pilots must request a contact approach: it cannot be initiated by ATC, and may be used as long as the airport has a published or special procedure, the reported ground visibility is at least one statute mile and the flight can remain clear of clouds. It allows pilots to retain an IFR clearance and provides separation from IFR and SVFR traffic. Obstruction clearances and VFR traffic avoidance becomes the pilot’s responsibility.

The main differences between the two approaches are the weather minima and who may initiate a request for the approach.

ONE MORE THING

All that is nice to know, isn’t it? But, what can you do if, despite your better judgment and prudence, you wind up being stuck up there and can’t get down, even if you have an instrument rating?

Obviously, if convective activity isn’t a factor and terrain isn’t either, and the cloud bases are high enough, an emergency descent could be done in some relative degree of safety, provided your instrument skills are up to it—and you have an instrument rating in the first place. Of course, there’s always the time-honored “180,” followed by a diversion to an airport with good VMC.

Then there’s the “find a hole” method. If it’s big enough, high enough and you know the terrain is flat enough, sure. But the implications of the phrase “sucker hole” are just as valid (if not more so) on the way down as they are for the trip up. And in case you thought I would forget, before you try any of the above, call ATC first. Don’t hesitate for a second to declare an emergency.

And remember those four Cs: Climb, Communicate, Confess and Comply. If you’re not instrument-rated, and make it back down, start work on the rating (after you’ve finished kissing the ground).

Jeff Pardo is a freelance writer and editor who holds a Commercial certificate for airplanes, helicopters and sailplanes.