Not long ago, I was conducting a two-day, six-flight, expanded instrument proficiency check (IPC) with the owner of an A36 Bonanza. We were above an undercast at 7000 feet en route from Wichita, Kans., to Emporia Municipal (EMP), a non-towered airport a short 25 minutes to the northeast. Had the skies been clear, we would have flown this VFR and I was going to present a “lost communications” exercise. As it was, we regrouped and flew IFR, the pilot under the hood the entire way. Not being able to pass up a good opportunity for distractions, I simulated failure of his only attitude indicator just after takeoff.

Shortly, I got my own distraction. We received an approach clearance recently that I’d never heard before, one that made me doubt one of the basic precepts of IFR flight. It may be something Aviation Safety readers look at and say, “Duh, everyone knows that.” I suspect, however, that many or most will not have received this clearance before, and may have been as confused about it as I was.

‘CLEARED FOR THE APPROACH’

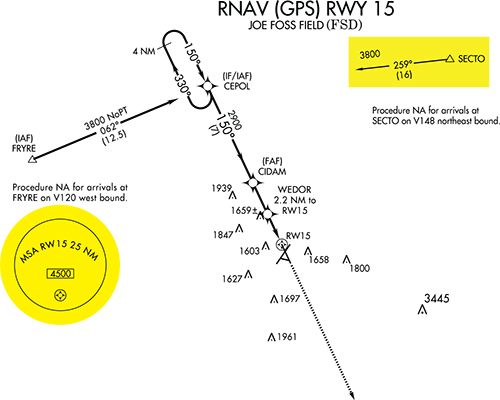

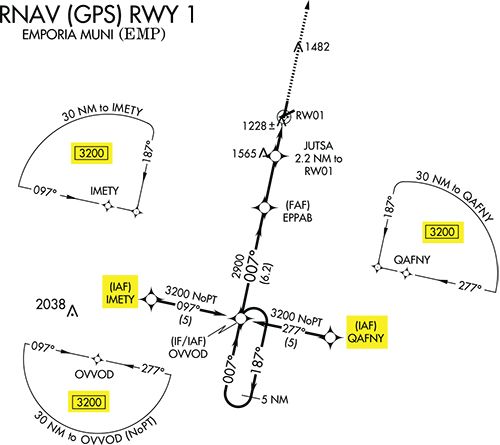

As we approached Emporia, my client requested the RNAV (GPS) Runway 1 procedure, beginning at IMETY, the initial approach fix on the southwest leg of the standard “T” approach. About 12 miles from the fix, ATC cleared us direct to it with the expected words, “Cleared for the approach.”

“We’re pretty close to the fix,” my student said. “Should I ask for lower?”

“You’re the pilot-in-command,” I replied. My client called Center to request a descent. That’s when the confusing thing happened. ATC replied, “You’re cleared for the approach. You can descend to the MSA.” He sounded upset that we hadn’t already started down.

My understanding has always been that you may descend for an approach when cleared on a Standard Arrival Route (STAR), on a published segment of an approach after being cleared, or when cleared to a specific altitude by ATC. This “cleared for the approach, automatically cleared to the MSA” was news to me. We confirmed the MSA in our area was 3200 feet; my student began the descent and flew a flawless partial-panel approach through the overcast and then simulated the rest of the way down to minimums. We discussed our mutual surprise at the “MSA clearance” after our flight; I told him I’d research it further and get back to him.

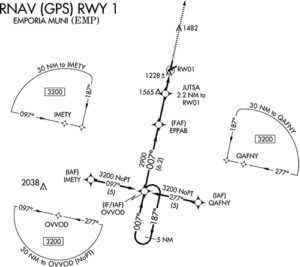

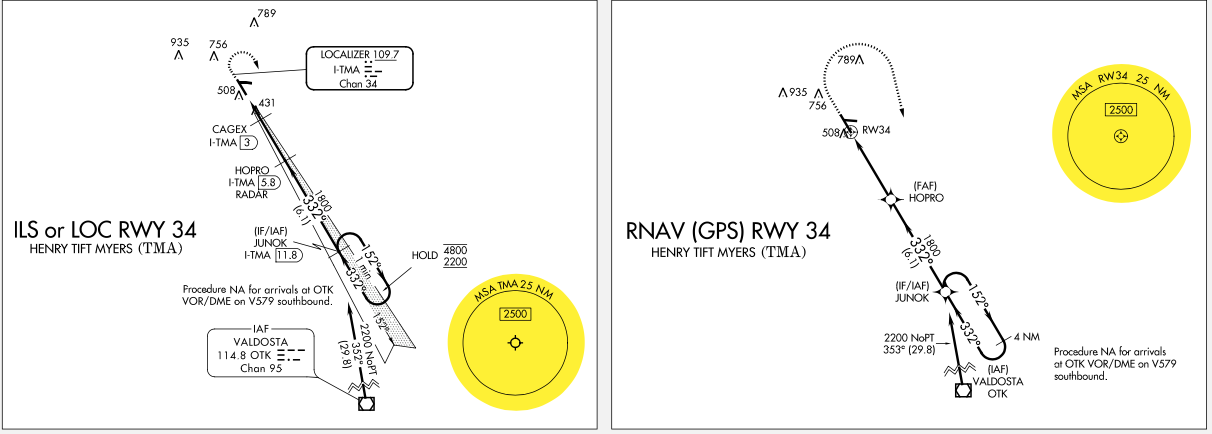

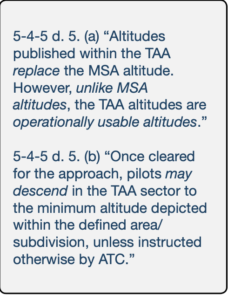

Figure 1: IPH definition of MSA Minimum Safe Altitudes are published for emergency use on IAP charts. MSAs provide 1,000 feet of clearance over all obstacles but do not necessarily assure acceptable navigation signal coverage. The MSA depiction on the plan view of an approach chart contains the identifier of the center point of the MSA, the applicable radius of the MSA, a depiction of the sector(s), and the minimum altitudes above mean sea level which provide obstacle clearance…. For RNAV approaches, the MSA is based on an RNAV waypoint. MSAs normally have a 25 NM radius…. Figure 2: An MSA And A Feeder Fix Figure 3: IPH definition of feeder route RESEARCH The question is whether “cleared for the approach” constitutes permission to descend to the minimum safe altitude (MSA) associated with that approach. My first source was the FAA’s Instrument Procedures Handbook (FAA-H-8083-16A). Chapter 4, Approaches, and the excerpt shown in Figure 1. The IPH’s description of the MSA outlines more about how they are defined and appear on charts—refer to the planview for the RNAV (GPS) Runway 1 procedure on the opposite page for an example—but in no way qualifies the declarative statement that MSAs are solely for emergency use. Meanwhile, the IPH section titled Instrument Approach Procedure Segments describes the means of descending from the en route environment to the initial, intermediate and final approach fixes. The MSA is not even mentioned. It does say, however, that “feeder routes provide a transition from the en route structure to the IAF. FAA Order 8260.3 (TERPS) criteria provides obstacle clearance for each segment of an approach procedure….” An example of a charted feeder route is reproduced in Figure 2 while Figure 3 is the IPH’s feeder-route description. And then we have terminal arrival areas, or TAAs. For RNAV-equipped aircraft, according to the IPH, a TAA “provides a transition from the en route structure to the terminal environment with little required pilot/air traffic control interface for aircraft equipped with Area Navigation (RNAV) systems. TAAs provide minimum altitudes with standard obstacle clearance when operating within the TAA boundaries.” This section does mention the MSA, thusly: “Altitudes published within the TAA replace the MSA altitude. However, unlike MSA altitudes the TAA altitudes are operationally usable altitudes” (emphasis supplied). Here’s where I think I’m starting to learn something. Continuing its discussion of TAAs, the IPH states (emphasis supplied), “An ATC clearance direct to an IAF or to the IF/IAF without an approach clearance does not authorize a pilot to descend to a lower TAA altitude. If a pilot desires a lower altitude without an approach clearance, request the lower TAA altitude from ATC. Pilots not sure of the clearance should confirm their clearance with ATC or request a specific clearance. Pilots entering the TAA with two−way radio communications failure…must maintain the highest altitude prescribed [in FAR 91.185(c)(2)] until arriving at the appropriate IAF.” “Once cleared for the approach, pilots may descend in the TAA sector to the minimum altitude depicted within the defined area/subdivision, unless instructed otherwise by air traffic control. Pilots should plan their descent within the TAA to permit a normal descent from the IF/IAF to the FAF.” In this statement, the concept of a “minimum” altitude is present, but the MSA itself is not referenced. Let’s keep digging for a better answer. The controller was correct: When we were cleared for the RNAV (GPS) Runway 1 approach at Emporia, we were authorized to descend to the MSA as long as we could determine we were within the circle (“defined area”) or sector (“subdivision”) of the charted MSA, which also defines the TAA. Since we were inbound from the southwest, this meant once we were within 30 nm of OVVOD, the IAF, we could (and should) descend to 3200 feet without further ATC clearance. This goes counter to what we were taught in the days before GPS, when terrestrial navaids were the only game in town. (It’s also counter to what appears as the “correct” answer on any number of IFR quizzes.) Importantly, this exception only applies when flying an RNAV (in our case, GPS) approach, most likely because—as the citation from the IPH presented in Figure 1 implies—we no longer have to worry about “acceptable navigation signal coverage.” Using ground-based navigation, a pilot might not be able to receive the navaid in use if he/she descends to the MSA prior to entering a published segment of that approach. With GPS, navaid reception is not a concern. AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL The FAA’s Order 7110.65, Air Traffic Control, often is referred to as “the Bible of ATC.” It’s the overall procedures document for controllers—and therefore pilots—when receiving ATC services. It can be a challenging read—not least because the latest iteration runs to 655 pages—but it does provide an approved, uniform set of guidelines for what’s expected from the controller’s point of view. Section 4-8 covers approach clearance procedures and provides a tremendous amount of technical detail on the subject, including this note under RNAV Application at the bottom of page 4-8-5: NOTE—1. Aircraft that are within the lateral boundary of a TAA, and at or above the TAA minimum altitude, are established on the approach and may be issued an approach clearance without an altitude restriction. Given that we’ve already learned that TAA and MSA are essentially interchangeable terms when operating with RNAV (GPS), this reinforces the policy that once within the TAA and cleared for the approach, we can (and are expected to) descend to the depicted MSA without needing to be on a published approach segment. WHAT DID WE LEARN? Put another way, when cleared for an RNAV approach, we should descend to the TAA’s minimum altitude, which is the MSA, as soon as we determine we are inside the defined area or subdivision of a TAA as published on the plate. I have never encountered this before, although it’s likely controllers routinely simply direct pilots to descend or give the “maintain at or above” altitude limit until on the published approach to avoid confusion. PEER REVIEW With something like this I wanted to get a professional opinion to back my research. I sent retired air traffic controller and current CFII John Foster the narrative above and asked if he feels I have interpreted it properly. John replied: “Let me start by giving your customer an A+ for asking ATC to clarify a procedure that he/she was not 100-percent sure of. So many pilots are reluctant to verify ATC procedures for reasons I do not understand. Perhaps they don’t want to sound stupid, bother the controller, are afraid they will get chewed out, etc. But whenever the pilot has a doubt about the situation, verify it. So, A+ to the customer. “I give the controller a B-. I say this because he was correct, you can descend, but not to an MSA. MSAs are ‘published for emergency use.’ They are not considered a published segment of an approach. The Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM) speaks to TAA approaches and TAA sectors as follows (emphasis added):” “Think of a TAA sector as a very broad feeder route. A feeder route provides published course and altitude guidance from a feeder fix to the IAF. The TAA sector works the same, but there is no feeder ‘fix’ identified. Rather, it is replaced by the location of the aircraft itself within the TAA sector.” ALWAYS LEARNING I’m the first to admit I don’t know everything, and that I’m still a student pilot despite an ATP certificate, 4800 logged hours and over 30 years as a CFII. But this lesson about a critical nuance of RNAV approaches was a real surprise. In writing this, I run the risk that many pilots and controllers will say, “How did Tom not know that?” But I suspect most pilots will say, “I didn’t know that either.” Either way, both my student and I learned something new that day. If it’s news to you too, then I’m glad I wrote this. When I began researching the MSA clearance issue, it was very tempting to log onto an aviation forum or bulletin board—or even social media—and ask my question. In other words, let someone else do the work, and hope they know what they are doing. As someone who spends way too much time online and on social media, I know what sort of answers sometimes float around out there looking authoritative while they are anything but. Do you have a question? Get into the books. Study resources like the FARs, your airplane’s Pilot’s Operating Handbook and its supplements, the AIM, Instrument Procedures Handbook, the Airplane Flying Handbook and other primary sources. As you answer your question, you’ll learn how to better answer future questions as well. Sure, it’s good to get a verifiably expert opinion like I did. But if you simply throw your question out there to the internet, you’re likely to get any number of conflicting answers with no good way to tell which is correct.

In the image above you show the ILS 34 and RNAV 34 into TMA. In this case, I don’t think the RNAV allows you to descend if all you get is “cleared for the approach” because it’s charted as an MSA. As I understand it (and I’m a new instrument pilot, so likely to be wrong), a TAA is also an MSA, but and MSA is not a TAA. In other words, if the chart says “MSA” on it, then it’s an MSA and and is only intended for situational awareness and emergency use. If you see the sector diagrams without “MSA” on them, then you’re looking at a TAA and clearance for the approach is also clearance to descend.

For a good example of this, look at the ILS 3 Y & Z approaches into TTA. The ILS Z is a typical approach with an MSA of 3400′. The ILS Y is a hybrid approach, which uses an RNAV TAA to feed into the ILS. If you look at the way the MSA is diagrammed on the Z approach versus the way the TAA is shown, the difference between the two is clear. It’s also interesting to note that the RNAV 3 uses an MSA rather than a TAA, so only the ILS Y 3 approach has the TAA.

It’s important to be clear on the distinction between a TAA and an MSA and know which you’re dealing with. If you’re flying an approach with only an MSA and you start your descent assuming it’s a TAA, you’re likely to hear those dreaded words “possible pilot deviation…”

Great example Geoffrey.

Geoffrey, I think you understand correctly. Or, I should say, my understanding is the same as yours.

The TAA is not limited to RNAV approaches as the author states. I’m a flight simulator instructor (jets), and I routinely use the ILS or LOC Rwy 27 in Memphis (KMEM). This is a TAA approach built around COVIM, the IAF. I’ll have crews at 5,000 ft, clear them direct COVIM, then clear them for the approach. Most pilots don’t realize they can, and should descend to cross COVIM at 3,000 ft, and they are professional pilots.

Although TAAs have been around for a couple of decades, they are not widely understood. I’ve been flying for over 50 years, and I’m still learning!

I’m not sure that your final example under “What Did We Learn” is accurate. Both the ATC Bible and the IPH are very clear – you can descend to a TAA altitude once cleared, not an MSA altitude. They are pretty much the same thing, but they’re not.

AIM 5-4-5 D. makes that clear, and it’s something you quoted in your article:

Altitudes published within the TAA replace the MSA altitude. However, unlike MSA altitudes the TAA altitudes are operationally usable altitudes.

If you’re flying an RNAV approach that depicts an MSA instead of a TAA, you are NOT automatically cleared to that altitude when cleared for the approach.

TAAs have been around for 21 years, so if an RNAV chart is still showing an MSA instead of TAA, there’s probably a reason for it – it could be traffic density (they tend not to want to use TAAs in high traffic density areas) or some other operational concern.

I have seen this issue on a number of forums recently. Because the TAA concept is a relatively new part of approaches for many pilots years beyond their formal training, it seems that it would be in everyone’s interest to modify the approach clearance language to something like, “cleared for the approach; descend per the TAA.”

Thanks for the article Tom.

I had always learned that the MSA was a good altitude to be aware of when you needed to get up and out of the way to deal with an emergency or other off-normal issue, or just to buy some time to regroup and figure out next steps. The TAA sectors function operationally as part of the approach; and once cleared for the approach they provide minimum altitudes to fly on your way to joining a traditional segment (at an IAF or IAF/IF). I can understand that the MSA and TAA sector altitudes may be related but not interchangeable. The controllers use of MSA in your example would have had me scratching my head as well.

A TAA segment is not an MSA. Unlike an MSA, a TAA segment is a charted altitude and used as if it is a feeder route to the IAF. A clearance for the approach authorizes descent to the TAA segment altitude once inside the TAA boundaries. If the approach does not have a TAA, you are never authorized to automatically descend to the MSA. The controller iMHO used incorrect terminology when he said your clearance authorized you to descend to the MSA. He should have used the proper terminology you are authorized to descend to the charted TAA segment altitude. MSA’s still appear on RNAV approaches, but there will not be both an MSA and a TAA charted on the same procedure. This is why you will see some ILS that have a TAA charted on their own charts as an ILS Y version while those with an MSA being charted as an ILS Z version. The difference is the TAA version uses RNAV to join the approach and uses a TAA for the feeder to the IAF whereas the MSA version uses conventional navigation systems and the MSA and you are only allowed to descend if you are established on a feeder route or a segment of the approach.

This note is provided to controllers in their equivalent of the AIM, FAA 7110.65Z

1. Aircraft that are within the lateral boundary of a TAA, and at or above the TAA minimum altitude, are established on the approach and may be issued an approach clearance without an altitude restriction.

MSA does not equal TAA. Use the proper terminology.

Also note you are on no specific altitude clearance in terms of crossing. Once cleared for the approach (without a corresponding altitude clearance) you are under normal IFR restrictions. You may simply descend to the TAA altitude or commence descent when necessary to cross the IAF at an altitude to cross the FAF at published altitude. This may include maneuvering for course reversal, so there is a lot of flexibility. And this agrees with TAA being the operational altitude. MSA only considers obstruction clearance and is therefore not operational.

When in doubt, Always ASK! MSP Center controls the airspace over our airport in NW WI (KAHH). The two RNAV GPS approaches (18 & 36) have IAP altitudes of 3,000 feet with the MSA within 25 NM at 3,200. I always get cleared to 3,000 verbally when cleared for the approach. Not sure if that is local procedure or not. Great research and explanation, Tom.

Losing my medical in the mid 90’s I haven’t become totally familiar with all the “new” issues related to GPS navigation and approaches. Therefore, with the majority of my professional flying experience of the past, I did find your article extremely interesting!

The company I used to fly for, out of Sioux City, IA, made many trips into Emporia, KS on a regular basis so just the fact you were going into EMP caught my attention. As you and many others commented, an MSA is typically thought of as something to refer to in an emergency type situation, such as compromised aircraft performance where it’s difficult to impossible to maintain a certain altitude, but not something referred to by a controller outside of an “emergency” context.

Thank you for providing a very informative article based on a real-life experience. This is how overall safety is maintained in this industry!