Something I discovered early in my career is that one of the easiest ways to combat complacency and maintain proficiency is to join the training department of wherever I am lucky enough to be flying. I know this is not always easy or even logistically possible, but if the opportunity arises, I will take it every time. At a previous job, one of the duties that the training department was responsible for was job interviews, both technical and practical. They usually involved about an hour of ground and an hour on a desktop simulator. It made sense, because the training department is in charge of taking these pilots and getting them up to speed. Who better to gauge the applicants than someone who will shortly be molding them into line pilots?

The job was entry-level, so the majority of applicants were instructors, skydiver or pipeline pilots. One thing that I consistently found lacking in these simulator evaluations was approach briefings. It sort of does make sense; for the most part, the applicants had come from single-pilot IFR operations in aircraft that do not have reliable autopilots. So, the goal is to cover as much ground as fast as possible, especially in the training environment where approaches are done one after the other.

To combat this pressure, I would actually pause the sim. I emphasized that I was not interested in the multi-tasking; I just wanted to evaluate how effectively the approach was briefed. Despite this, I noticed frequent deficiencies. Instrument training effectively manages to teach using the approach plate as a pseudo checklist to make sure everything is set up, but a practical plan on how the approach will be flown is sometimes forgotten. The following tips can help increase situational awareness, prevent complacency and increase crew resource management, even when you are flying single-pilot.

Load the approach

Loading the approach will increase situational awareness, give DME information and guidance on approach transitions and missed approaches.

Set the frequencies

Depending on how fancy your avionics are, this may already be done!

Set your course

This one vastly varies depends on your equipment. If you can switch your NAV source and your avionics will save the previously set course, it will be one less step when you are getting vectors or flying the approach transition.

Set your minimums

This can be done with a radar altimeter, or even an altitude bug on your altimeter.

BUILD IT, THEN BRIEF IT

A habit that many of us developed in instrument training is setting up and briefing approaches fairly late. This is most likely due to the fact that training is already expensive, so there is always a secondary goal of maximizing efficiency. This means sticking to close-by airports, and planning approaches with minimal gaps. When you transition out of the training environment, time is your friend. Get the weather/Notams as far out as you can, or even before you depart. If you set up and brief the wrong approach, which can happen, it will take no longer to redo everything than if you waited and something happened to change. If nothing changed and you set up and briefed the correct approach during the safest phase of flight, you are now free to navigate the terminal and approach phases focused on actually flying.

As I mentioned above, many pilots use their approach plate as a checklist for setting frequencies, getting the ATIS and so on. This is a fine technique, but it can be more effectively done as a flow and then utilizing the plate to double-check your work. Said flow will be different for every aircraft setup, because how you fly approaches will vary vastly depending on the equipment you have.

I can give some examples of what a flow could include, but it is up to you which exact procedure works best for you. Once you develop a good flow, practice it every time and you will have a two-step process that will help eliminate mistakes or omissions. For example, the four-step flow I use to set up approaches in a legacy PC-12, with a Garmin 650/750 suite and a three-axis autopilot, is summarized in the sidebar above. I then confirm it with the plate.

If you are shooting approaches with an airplane meeting only the /U equipment code, setup may just be setting the frequencies and listening to the ATIS. However, by making it a consistent routine, you will not have to stop during your briefing to set anything up and things will flow more smoothly.

SPEAK UP

Now that your approach is properly set up, you can navigate your approach plate. For the below examples, I will assume most readers are using FAA charts, and not Jeppesen. The advice can still work regardless of your preferred brand of chart, but the sequence will be referencing FAA published approach plates.

The first common steps, verifying the proper approach and confirming everything is set correctly set, is easy and not something I typically find issues with. The remarks section is where I tend to see people go one of two ways. Either they will carefully read the whole section, or whip through it at the speed of sound. It is easy to see why both commonly occur, because you do not want to miss anything, but probably close to 90 percent of the time, there are not remarks pertinent to your approach. My recommendation? Read the remarks, and then verbally announce there pertinent ones, if any. I am a big fan of verbal briefings, even if you are single-pilot. It helps reinforce important points and combats procedural drift. You may sound a bit crazy if you are briefing verbally around an unsuspecting passenger, but it is well worth the silly feeling if it breaks a link in the accident chain.

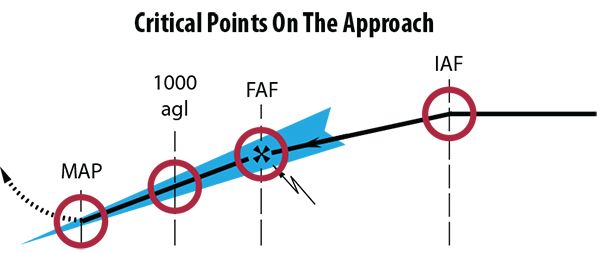

As mentioned in this article’s main text, management of critical approach points is crucial in preventing challenging snap decisions. By definition, these are choices made quickly, sometimes with inaccurate or incomplete information and with potential outcomes that can adversely affect safety of flight. There are several points during the approach that these judgment calls should no longer be made, listed below. If you do not meet the desired conditions, the approach should be aborted. They include:

Intermediate Approach Fix (IAF)

The approach should be built and briefed. Additionally, the configuration schedule should be considered. If you are behind at this point, you can always request a hold!

Final Approach Fix (FAF)

In a perfect world, all your checklists and configuration changes will be complete by the final approach fix. At a minimum, the aircraft should be in a position to begin descent down the desired flight path.

1000 Feet AGL

The aircraft should be stable, on speed, configured and the checklists complete. If this is not the case, ask for vectors back around. The approach will be much easier to fly without the added variables, and those ugly snap decisions can be saved for another day.

Missed Approach Point (MAP)

Most people plan to land from an approach, and if enough goes wrong, execute the missed. I suggest the opposite. Plan to go missed, and if the stars align, you can continue to land. Adjusting this mindset can go a long way toward preventing continuation bias.

CREATE YOUR PLAN

Something that is always worth considering is how you are going to fly the approach. In what configuration and at which airspeed will the approach be conducted? When will the configuration changes occur? What is the aiming point? Or, more importantly, at what point will you go around if you have not touched down? When and at what altitude will you be stabilized with checklists completed?

Answering these questions will help you stay ahead of the airplane and prevent those dangerous snap decisions pilots can be forced to make. Snap decisions such as, “I missed the GS, but I can still recover it,” and, “I am floating, but I still have enough room to land.” Drawing a firm line in the sand at critical approach points, such as the final approach fix, can ensure you do not end up on the losing end of a bad bet.

TWO ROADS DIVERGED

In eighth grade, my English teacher had the whole class memorize the poem “The Road Not Taken” by Robert Frost. At the time, I could hardly think of a more profound waste of my time. Funnily enough, I still remember it today and it pops up in the most interesting places. The first verse starts with this: “Two roads diverged in a yellow wood, and sorry I could not travel both.” Of course, this is a metaphor for finding the path less traveled, but it can aptly apply to approaches as well.

Every approach has two possible endings, and both should be given equal consideration. Of course, unless you are conducting training, your goal is to land and taxi to the ramp. That mindset is why it is so important to plan for a missed approach every single time. The one time it is gentleman’s IFR, say 1000 feet overcast and 10 miles of visibility, the ILS will get you in 10 out of 10 times.

There are exceptions, of course. Recently, I was in a familiar crew, flying a familiar airplane and shooting a familiar approach. At about 600 feet agl, it was clear the aircraft in front of us was unable to exit the runway. We called a missed approach, and the controller did not have a plan ready for us to go around, so we had to execute the missed as published. If anything had not been set up, or we were not ready to execute the published missed, it would have been a different story. Especially those of us operating single-pilot with no autopilot, the workload can drastically increase without prior preparation.

Threat error management, or TEM, is the FAA’s answer to accounting for human performance in the complex environment that exists whenever we operate aircraft. The three basic components to this are threats, errors and undesired aircraft states. Something that should be accounted for in every approach (or departure) briefing is the potential threats you anticipate.

A threat is defined as “events or errors that occur beyond the influence of the flight crew, increase operational complexity and must be managed to maintain the margins of safety.” There are two major types of threats, environmental and organizational. Environmental include things like weather, ATC, airports and terrain. Are there thunderstorms, icing or a contaminated runway? Is there a different procedure to mitigate these threats? Organizational threats include operational pressure (get-there-it is), aircraft issues or cabin issues (ever had a sick passenger?).

Recognizing and briefing these threats before they become hazardous is key. Most major incidents and accidents had a sort of tipping point where the last line of defense (the crew) could no longer prevent disaster. The earlier these threats are detected, the easier they can be mitigated.

CAN I LAND YET?

You have built and briefed your approach, and you are approaching minimums on a beautiful, stabilized flight path. When can you depart decision height/decision altitude (DH/DA) or minimum descent altitude (MDA)? Most proficient aviators can point to the FAR 91.175 list of markings and lights which, if seen and identified, allow the transition from the approach phase to the landing phase. It is worth reviewing. Your approach plate also very helpfully describes what you should expect to see, so long as everything is working. Remember, some lights only allow you to descend to 100 feet above the touchdown zone elevation (TDZE). Do you remember which ones?

One last important thing about runway lights: Don’t forget to turn them on. If you are flying into a non-towered field, ensure you know the pilot-controlled lighting (PCL) lighting frequency and hit that sucker as many times as is your preference. I recommend doing it at the final approach fix, because it is a useful trigger, and it will ensure the lights will stay on until you are in a position to land.

IS THAT IT?

I know this whole thing seems very long-winded, but it is important that approach briefings be scaled to the complexity of the procedure itself. A briefing for a standard ILS to a familiar airport on a decent-weather day should be much shorter than a non-precision circling approach to an airport you have never visited before. A proper building and briefing procedure will make sure there is a layer of consistency to your instrument flying and will help prevent error buildup. And if something does go wrong, you have a plan in place for the missed anyway. Who couldn’t use that good practice?

Ryan Motte is a Massachusetts-based Part 135 pilot, flight instructor and check airman. He moonlights as Director of Safety when he isn’t flying.