The drones—they are among us. Though not yet as prevalent as Canada geese, their number has exploded as economies of scale in manufacturing and the Moore’s law effect have resulted in both lower prices and greater capabilities with each successive generation. From an aviation safety standpoint, these are the drones you should be looking for because you are most likely to encounter them.

Understanding how drones—in FAA parlance, an unmanned aircraft system (UAS) is sometimes called a drone—are used is the first step toward avoiding an unexpected and unwanted encounter. In its recently released Part 107 regulations on commercial use of UAS, the FAA focused on small UAS, craft weighing under 55 pounds. Given their numbers and popularity, this is the class of systems with which we should be most concerned.

Numbers Rapidly rising

For decades, we general aviation pilots have shared the airspace below 400 feet agl with modelers flying radio-controlled craft. Flying model aircraft solely for hobby or recreational reasons does not require FAA approval. Instead, hobbyists are advised by the FAA to operate RC models in accordance with guidelines in the agency’s Advisory Circular AC 91-57A, Model Aircraft Operating Standards.

Those are strictly non-commercial operations of the same basic technology used in drones. The big difference is industry wants to operate that technology commercially, and that’s where the FAA’s new FAR 107 regulations come into play.

The Consumer Technology Association (CTA), in an August 2016 press release lauding the FAA’s commercial drone regulations, projected the U.S. drone market will reach record highs in 2016, with predicted sales of 2.4 million new units. All told, the UAS industry projects about 3.5 million new drones since 2014. And the number of drones in the 55-pound-and-under category potentially estimated to be in service will be greater than four million. For comparison, the North American population of Canada geese is estimated at between four and five million.

Most of the drones on today’s market are quadcopters ranging from $400-$2000. Manufacturer DJI is estimated to have 75 percent of that market, thanks to the popularity of its Phantom series. My Phantom 4 tips the scales at around three pounds (and lightens the wallet by $1200). The more robust Inspire weighs 6.5 pounds but can carry an additional payload of 1.5 pounds, bringing it up to eight pounds. Fully tricked out, it can cost $4000-$5000. Meanwhile, a male Canada goose weighs between 3-13 pounds, and costs little.

In January 2016, the FAA announced it had received 300,000 drone registrations, numbers that may be skewed by commercial users who are seeking immediate compliance for their commercial-grade or “prosumer” (professionally operated, industry-specific) drones. These types of drones are less common than garden-variety quadcopters and tend to have greater weights and significantly higher price tags. At the high end of the market are hexa- and octacopters with maximum takeoff weights up to and beyond the FAA Part 107 maximum of 55 pounds. Generally speaking, as the price of the craft and the value of its payload goes up, so does its operator’s professionalism.

Conflicts

As the drone population grows, conflicts with commercial and GA aircraft will be inevitable. So far, however, they have largely been avoided. If anything, drone encounters have been over-reported in the general media, giving an exaggerated sense of the risk and danger. There have been headline news stories about drone sightings near major airports, like JFK, and in the UK a stray plastic bag was reported as a drone strike by a major airline.

On the other hand, a reasonable argument can be made that even when the number of drones surpasses the number of geese, drones will still pose a lesser risk because the birds are in the environment 24/7 and ready, willing and able to fly in large groups for hours on end, day and night, particularly as migration instincts beckon them south. By comparison, a typical drone will fly at most a few hours on a good day (the Phantom 4’s battery life is roughly 30 minutes) and spend most of its time on the charger or packed away in a closet.

I am not trying to downplay the inevitable encounter—it will happen. I just want to put the likelihood into perspective. So far this year, there have been far more close encounters with Canada geese and other large birds than drone encounters. Despite our fascination with the “miracle on the Hudson,” close encounters with birds don’t make the headlines the way drone sightings do.

The Enemy Is Us

While pilots chauvinistically protect the sanctity of our shared airspace and worry about the day when a UAS collides with a larger aircraft, the greatest risk from a small UAS is to people near the drone. There are many YouTube fail videos of drones flying into people, crashing events, wedding parties, athletic events and concerts. The greatest danger from drones is the desire to play with one and not take the technology seriously. The result is injury to the operator, intended subjects or innocent bystanders.

I have witnessed and even caused drones to fly into buildings and trees. I have heard and read accounts of injuries and damage to people, animals and property. More often than not, the injured party is the drone pilot or perhaps the subject the drone pilot is trying to capture on video. The damaged property is usually the drone.

When control over a drone is lost, people often reach for the craft to control it by hand. They forget it is held aloft by spinning blades. While reaching for a drone to protect others is a noble thing, it ignores the first rule of safety and rescue: Don’t create another victim. While made of carbon fiber or plastic, the spinning blades of a quadcopter are not benign. They can slice skin, cause contusions and even poke an eye out.

Avoiding the Drone Zone

To manage this new risk, pilots need to better understand the psychology of drone flyers (both recreational and commercial). With most small UAS operations restricted to flying below 400 feet agl, pilots should expect conscientious folks will follow the rules, but—not to be too cynical—pilots shouldn’t count on good behavior. Like speed limits on highways, compliance is voluntary and largely unenforced.

Most drones will be found operating in line of sight of an operator and below 400 feet agl. Also, practically speaking, drones are self-limited. While a typical drone can operate at distances of five kilometers from the controller, most consumer-grade UAS do not operate reliably at this distance without modification. With average battery life under 30 minutes, most drones will stay close to home.

The best policy is to expect exceptions, which may be concentrated in a few obvious places. Just as Canada geese are found near wetlands and waterways, drones concentrate in areas that are somewhat predictable. For the most part, encounters with drones will be significantly more likely when you are within 400 feet agl, but here are other times and places to keep an eye out.

What You Need To Know About FAR Part 107

Class G

The vast majority of airports in the United States have no control tower. Under FAR 107, commercial drone operators are not required to communicate with nor give notice to airports in Class G airspace. Part 107 encourages small UAS to avoid interference with manned aircraft, but does not require communication nor does it require avoiding approach or departing corridors at uncontrolled airports.

While this sounds potentially menacing, you may also encounter a Nordo aircraft also legally accessing the skies at such an airport. Such an aircraft would be well within the law and much bigger. Keep your head on a swivel, and if the uncontrolled airport is near a landmark or scenic attraction, clearing traffic should include a scan for drones over hot spots like public parks. When I cross any river on final, I scan for waterfowl. When I fly over a park or golf course, I scan for drones.

400-Foot AGL Exception

Part 107 requires commercial drone operations remain below 400 feet agl, but there is an exception allowing a small UAS to remain 400 feet from the tallest object in an area. So a 1000-foot-tall tower, bridge or building now has a 400-foot cylinder around it where drones can operate extending to 400 feet above the structure.

NOTAMs…Or Not

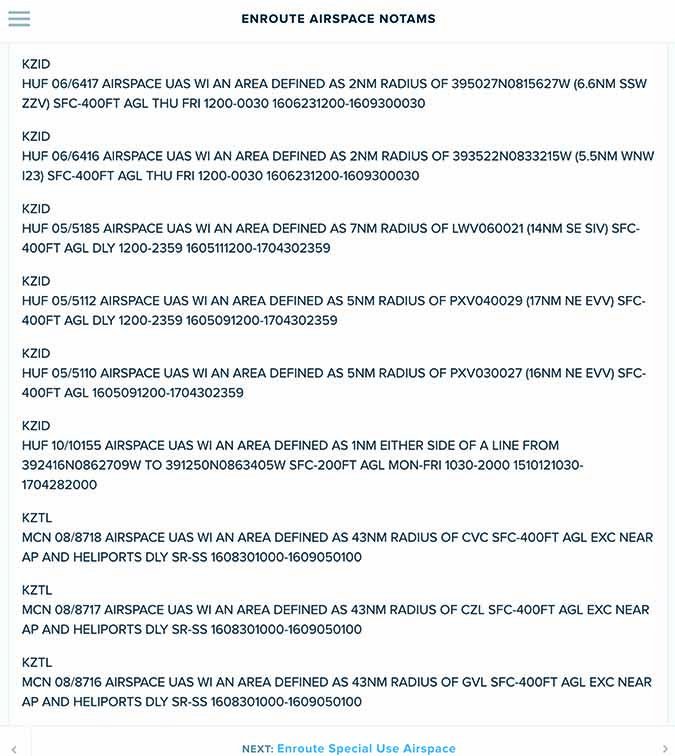

Prior to FAR 107, drone operations in the vicinity of airports were subject to Notams. To avoid cluttering the Notam system, this requirement was thankfully eliminated. Drone operations within Class A through E airspace require ATC permission, but not necessarily a Notam. However, commercial drone operations that are granted exceptions—rules like weight limits, night operations or other restrictions in Part 107—may result in a Notam. Since the FAA holds pilots accountable for briefing themselves on all aspects of an intended flight, you are expected to read Notams and be aware if a drone is operating in the vicinity of an airport.

Points of Interest

Try this exercise: Choose a point of interest in your area. Now search for “quadcopter video” plus the name of the point of interest. Chances are you will turn up a wide variety of videos showing major landmarks, rivers, buildings, parks, etc., and in all likelihood they will be within five miles of your home airport.

While the rules restrict small UAS to remain within 400 feet of the surface or structure, they’re capable of flying into the flight levels. This means you can encounter them pretty much anywhere your Cessna can go, and maybe even a bit beyond. My DJI Phantom 4 has a service ceiling of 6000 meters, which is nearly 20,000 feet. It is rare to find drones at these higher altitudes, but it is not beyond the bounds of imagination to think someone with a newly purchased drone might read the service ceiling and want to put it to the test.

Why Are You So Low, Anyway?

In many ways, some of the pilots at greatest risk from drones are those in news helicopters who are paid to rubberneck at the same events that drones are peeking at. Crop dusters and rescue choppers fall into this category as well.

Typical fixed-wing operations are not likely to be in the so-called “drone zone,” from the surface to 400 feet agl, unless there’s an airport nearby. If we’re adhering to FAR 91.119’s minimum safe altitudes, we’re expected to stay 500 feet from people or structures, plus 1000 feet above and 2000 feet horizontal over congested areas. If you deem it safe to drop below 500 feet agl for a better view or for the thrill of the scenery whizzing by, you are now encroaching into the shared airspace that is generally the domain of drones. It is not illegal to fly a fixed-wing aircraft below 400 feet agl if you remain at least 500 feet away from people or structures, but this is not a typical GA operating altitude except when landing or taking off.

The closer you are to 400 feet agl, the closer you are to the Drone Zone, a space also occupied by power lines, towers, trees and other obstructions, not to mention a substantially higher density of birds like Canada geese. Any of these are an excellent reason for GA pilots to stay clear and—while drones are a popular thing for pilots to complain about—this isn’t really airspace we tend to linger in because it’s rife with other hazards.

We Must Learn to Coexist

The FAA’s new rules and standards for commercial drone pilots will both help them avoid larger aircraft and reduce the risk for GA pilots. Knowing that remote pilots will be held to these requirements should give the rest us some solace that remote PICs will be well informed, prepared to share the airspace responsibly and follow rules that make a great deal of sense for protecting all involved.

They also reduce the risk by making it clear how, when and where small UAS operations are allowed and under what conditions. Risks are further mitigated by increased industry education, guidelines and software that often prevents or at least warns small UAS operators of proximity to airports and airspace, and often prevents operation above 400 feet agl without an override.

That said, mitigated risk is not the same as no risk, and regulating professionals who operate drones for hire is not even close to regulating the unwashed masses who can pick one up at Walmart and buzz the airport as soon as the battery is charged. With four million more drones, there is no question the risk of conflict has gone up.

Like it or not, Class G airspace below 400 feet agl is now the Drone Zone. We share this airspace with UAS operators who have as much right to it as we have, and there are already far more FAA-registered UAS than there are GA aircraft. The best thing pilots can do is redouble our efforts to keep an eye out, avoid potential trouble spots, stay aware of our surroundings and hope that the person on the other end of the controls of the UAS will be doing the same. See and avoid just got a bit more challenging, but you are still more likely to hit a goose.

Mike Hart is an Idaho-based flight instructor and proud owner of a 1946 Piper J3 Cub and a Cessna 180. He also is the Idaho liaison to the Recreational Aviation Foundation.