Theres little I find more exciting than launching for a new destination across unfamiliar territory. Exploring the great unknown makes adventurers out of pilots who use their planes for, you know, actually going places. But, getting there requires a little-sometimes a lot of-extra planning.

My bride enjoys the adventure of personal airplane travel as much as any pilot; she also appreciates the added risks involved when tackling new terrain, new airspace,

288

new weather systems and new destinations. Shes such a good sport, in fact, weve enjoyed the thrill many times.

Our first “real” trip took us on a 2300-mile journey starting only five days after passing my private pilot checkride. Then, there was our first time to Sun n Fun; to coastal North Carolina and the sands of the Wright Brothers; our first flight to Oshkosh and-well, you get the picture.

We also made a couple of international trips that still stand out years later: Key West to Grand Cayman for one, and Cancun, by hugging the Bay of Campeche to Vera Cruz, then the West Yucatan city of Campeche and across the Yucatan. The latter one took two days each way.

If, like us, you harbor unfulfilled ambitions to continue such adventures via personal airplane, you probably understand part of what made each of those trips an adventure was the added challenge of flying into a new unknown. To face those added challenges, we engaged in considerable extra preparation compared to the routes we fly repeatedly.

Domestic Destinations

But you dont always need a passport to get seriously off your beaten path. An excellent example of a domestic trip that demanded extra preparation came in January 2000, with an opportunity to fly west from my home in Wichita to Las Vegas.

This was a tandem flight-as in two pilots in two airplanes. Since our itineraries diverged after Las Vegas, your esteemed editor planned to fly his plane and I planned to fly mine. This trip exposed me to a new routing across unfamiliar terrain to two airports unknown to me.

Without prudent extra-effort advance work we both put forth, my comfort level wouldnt have been very high. For me, anyway, the cure is easy-I simply return to the same spot Ive always gone before flying into the unknown: to my beginnings, like a student prepping for the checkride.

Whats Not to Check?

If youre like me, you plotted out your solo cross-country to a level seldom since repeated (See page 12 for more details on modern VFR flight planning-Ed.). The prep work needed for that first solo cross-country-or your first foray into high terrain, oceanic flying, remote locations or congested airspace-should be oriented more toward the cerebral aspects of the flight than the mechanical ones.

From my perspective, any sojourn into unknown territory demands extra advance work to prepare for whats new and different. Lets take a look at some of the elements to cross off the checklist.

Weather

For example, you probably know well the impact of various meteorologic phenomena when you stay close to home or venture out on a familiar routing. But when the trip takes you across time zones and weather systems, the need to be watchful goes up a notch to help obviate any sudden surprises.

Patterns you see at home cant be counted on a thousand or more miles away, which means dealing with new local patterns as well as any distinct micrometeorology you may encounter.

My usual practice has me watching weather patterns several days in advance of my planned departure, becoming more focused the closer it gets to engine-start time.

Do frontal passages between here and my destination tend to produce results similar to what I see at home? What are those results? Evening fog? Morning fog? Does a typically humid valley suffer with visibility-challenging haze?

When crossing time zones, how about crossing multiple weather systems? Have they produced rain storms, lightning or worse weather-like tornados?

Watching weather patterns as they play across your route and destination could bring you to make a new decision regarding your route, your departure time or even your departure day. Or whether to go at all.

Routing

Meanwhile, youre looking at the appropriate charts. Did you note those mountains? The minimum safe altitude along your propsed route is a heckuva lot higher than pattern altitude at home, isnt it? Or what about that restricted area? Can you get there from here?

What if youre VFR-only and unexpectedly face IFR conditions? Will the terrain give you room to make a new decision-even the highly touted 180 turn? What about the likelihood of ice at that altitude? Yes, even in the summer over the Lower 48, normally aspirated airplanes can get high enough to see significant airframe ice accumulations. Are you ready to deal with that? Is the terrain low enough you can descend to warmer air without smacking into something?

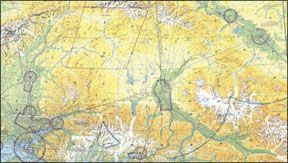

For our trip to Vegas, the route that made the most sense for two normally aspirated piston singles took us southwest out of Wichita to south of the Sandia Mountains and back up to Albuquerques Double Eagle II Airport (AEG). After a fuel and nature break, we planned to continue to Las Vegas for a landing at the North Las Vegas Airport (VGT).

We couldnt make VGT nonstop from Wichita, that was a given. But we based our fuel stop on our desire for a break as far beyond the halfway point as we felt comfortable. For us, AEG fit the bill, 509 nm away, with an ETE of 4:30 for my Comanche. That left the second leg at 433 nautical and a 3:45 ETE. Very manageable. But the distance and time remaining after a planned fuel stop wasnt the only consideration.

MEA

Since the terrain out there is high, so should be your cruising altitude if you want to remain as far above the bumps as possible, and retain some glide capability in case that fan up front quits.

How will a higher-than-usual cruise altitude impact your groundspeed and your fuel flow? What about supplemental oxygen, even if youre not going so high its required?

We also factored in headwinds typically found flying westbound in the winter; the headwinds were less than expected and our reduced groundspeed was mostly due to our high cruise altitude and lower engine power. Despite these factors, we faced no fuel issues since both legs ended left us with more than two hours of fuel at landing.

Terrain

Things that can go bump in the sky can put a dent in your flying day, another reason for a little added familiarization. Does the route and planned cruise altitude take you adjacent to-or even below-nearby terrain? Should you need to divert, will terrain pose an issue?

After contemplating a direct routing, we opted to follow Victor airways. This allowed us to avoid the highest terrain, one benefit of which was remaining low enough to cross some of the mountains east of Albuquerque and still retain some excess performance. Staying on the airways also enhanced the likelihood of radio and radar coverage, not to mention VOR navigation capability in case our then-newfangled GPS navigators got confused.

On both legs, we flew at altitudes where supplemental oxygen was the only smart thing to do, regulations aside. With a night landing ahead at VGT, the improved color acuity of supplemental oxygen was welcome. And it made all that neon veritably explode out of the darkness of the adjacent desert.

We considered other terrain issues beyond the mountains. With much of the route uninhabited high desert where airports are few and far between, it seemed prudent to carry some extra water and snacks-just in case of an unplanned downing.

Taking stock of the height and type of terrain over which youll fly should be a mandatory item for every first-time leg. And if you dont like what you see, find an alternate route.

Airports

At your destination and at any intermediate stops, you need to make sure facilities exist to serve your airplane and your passengers. First and foremost, of course, you want enough runways-one long enough to land and launch from when the plane is heavier and the day is hotter. And pay attention to the runway orientation. If the weather news was good to you, the runway will work with the demonstrated crosswind component. Otherwise, a different airport may be in order. Or a delay.

Dont forget fuel; these days, take nothing for granted where the go juice is concerned. For example, if you absolutely need a specific type of service, youre likely already used to calling ahead and asking for it.

But even double checking the 100LL supply is recommended today; theres nothing more frustrating than landing and learning the field ran out a couple of days ago-or shortly after you took off.

Arriving at night? What sort of lighting system does the airport use? How many clicks for the PCL system? How about the beacon? Are all runways lit, or just the longest one-you know, the one with the guaranteed crosswind?

What about the available IFR approaches-do you have all the airborne equipment like ADF or DME necessary to fly some remote localizer-only approach?

Finally, in what kind of environment is the airport located? For example, AEG sits out in the desert west of Albuquerques urban (and well-lit) areas, making it easy to find at night. Conversely, VGT is in one of the worlds highest concentrations of electric lights. Even Lindbergh had trouble picking out Le Bourget in 1927-you might not find your destination airport the first time, either.

Of course, you do check all Notams, right, not just those advertising the latest TFRs?

Timing

My favorite travel philosophy is, “Well be there when we get there.” Nonetheless, there are many elements that should factor into the timing of a first-time trip.

Looking back, we spent a couple of hours together and separately, planning our route to VGT, estimating performance, looking up facility information and corralling charts. Since then, weve both flown that route several more times, each time marveling at the scenery and the personal airplanes utility and versatility. But doing it right the first time took planning and some attentive thought. Thats one reason were still around to write about it.

Dave Higdon is a professional aviation writer/photographer with several thousand hours of flight time.