If you flew much before September 2001, you may never have heard of a temporary flight restriction, or TFR. If you had, it’s likely you became familiar with them as they were created to provide a safer environment for firefighting aircraft operations. Since 2001, they’ve been known to pop up every time a sitting president left the White House for a fresh Danish, or went campaigning or golfing.

While wildfire TFRs don’t usually come with the threat of a pair of F-16s, the red circles depicting wildfire TFRs pop up every summer on aviation charts like weeds. While they can and are created any time special flight operations need to be protected from typical civilian traffic, they’re especially pernicious in the western U.S. Staying safe should be simple, right? Just load the TFRs onto your moving map and skirt their boundaries, right? It isn’t that simple: Skirting the boundary is perfectly legal but it may not provide much of a safety margin. In fact, skirting them actually could increase your risk. To truly reduce the flight safety risks related to wildfire TFRs, we need to understand their implications.

Why TFRs in the first place?

Wildfires act like a magnet for fixed wing and helicopter aviation operations, attracting fire bombers, tankers, smoke jumpers, helitac crews and reconnaissance aircraft, with their operations concentrated over the active wildfire area. Hence, the TFR. The zone inside the TFR is a hub of concentrated operations, usually in significantly reduced visibility, with numerous aircraft cleared into and out of the airspace by airborne fire controllers, who are typically managed by the agency fighting the fire. Think of wildfire TFRs as a particularly active beehive, with the most concentrated activity going on in the hot zone.

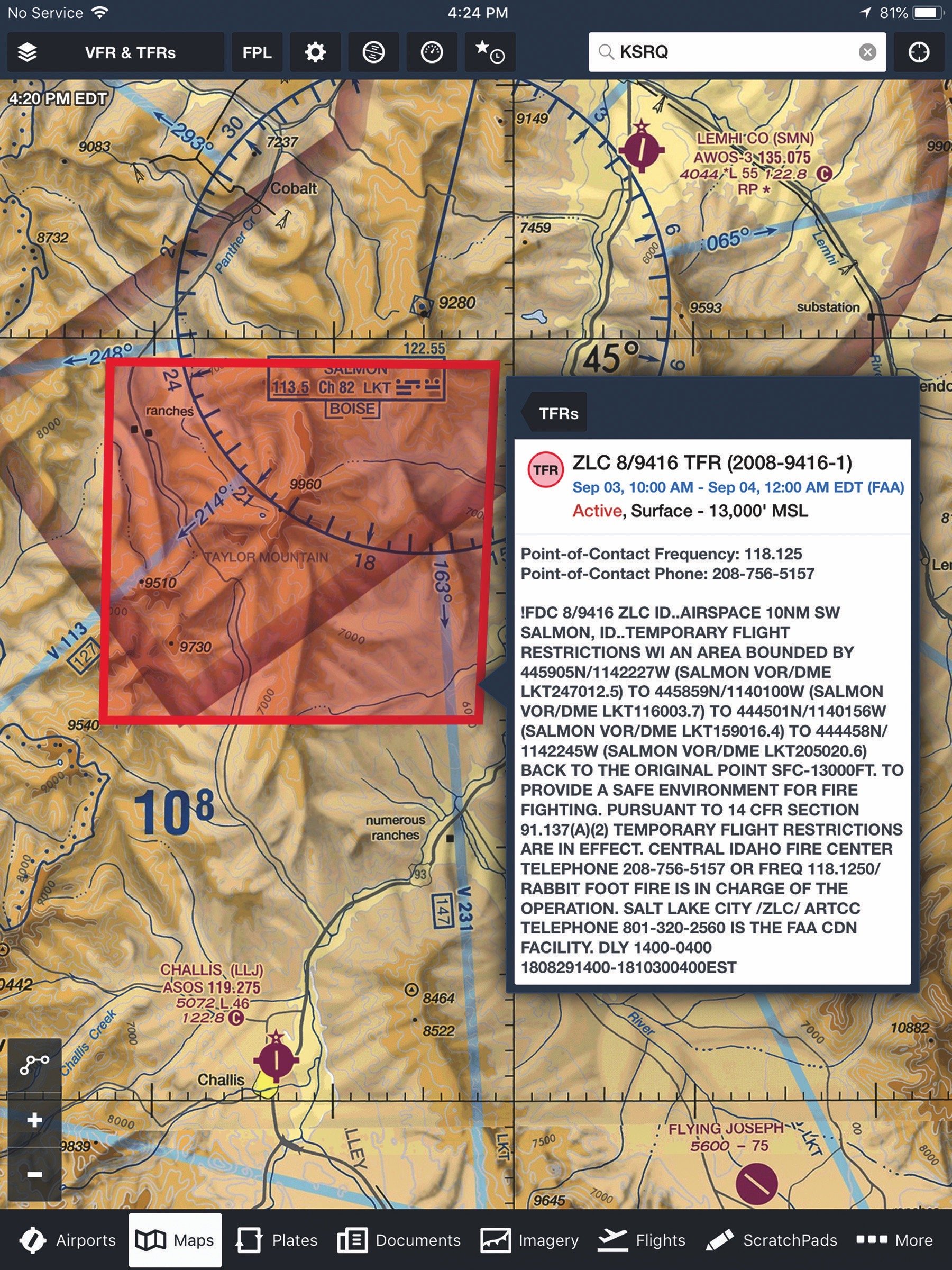

Where are all those aircraft coming from? For any given fire TFR, there are one or more firebases—usually outside the TFR—where support aircraft and personnel originate. This means there can be one or more corridors between those firebases and the TFR itself. Quiet little airports near large fires can begin to look like a hub-and-spoke network when firefighting operations move in. This summer in Idaho, the U.S. Forest Service helibases located at the Lemhi County Airport (KSMN) in Salmon, Idaho, and the Challis (Idaho) Airport (KLLJ) have been busy supporting fire operations on numerous fires, including the Rabbit Foot Fire, located only 10 miles north of Challis and 10 miles southwest of Salmon. (The ForeFlight screenshot on page 13 details the two facilities’ positions relative to the associated TFR and a nearby Vortac, as well as possible routes between the TFR and the airports.) The firebase at McCall, Idaho, was so busy that a temporary control tower was put into service. All of these usually quiet little mountain airports are hubs for traffic going in and out of the numerous TFRs in the area.

In many ways, TFRs are like busy Class Bravo airspace in that the aircraft heading into a TFR must have a clearance and altitude assignment beforehand. Their crews are busy configuring and navigating, and might not be looking for you as you stumble through. If there are too many aircraft inside the TFR, aircraft outside the TFR are frequently told to hold. This means that the airspace adjacent to, but outside, the TFR can be busy with aircraft who might appear to be pointed away from you at first but soon may turn around. In the U.S. Fire Service operations, aircraft must establish two-way communication prior to the 12-mile mark and must have a clearance to proceed inside the seven-mile mark of an incident fire, even before a TFR is established.

When planning your route around a fire TFR, look at the sectional and imagine lines radiating out from the center of the TFR to the nearest airport(s). That will indicate possible traffic corridors. Better yet, do some further research to find out where the aircraft that are fighting the fire are based. You should expect that the corridor(s) from the base(s) to the TFR will be busy and assume there may be aircraft holding outside the boundaries of the TFR, most likely on the side with the nearest airports supporting the fire. These aircraft are themselves waiting for clearance to go into the TFR.

Operating near Helibases

Many pilots may have some concept of the tempo and frequency of flights to and from an airport when a seasonal firefighting operation bases its fixed-wing aircraft at an otherwise underused rural facility. Helibase operations add even more complexities, a lot of which may be unusual and unexpected.

For example, the helibase at Salmon is located at the southeast corner of the airport. To reach the current large active fire to the southwest, helicopters swinging buckets will routinely transit the Runway 35 threshold as they head off to nearby bodies of water and then to the fire. When they return for fuel—traffic allowing—they cross the runway centerline again. When working any active fire, the traffic is a nearly steady stream, with one copter coming in while another is leaving. The combination of increased traffic and the inevitable smokiness (visibility is often reduced to between three and five miles) dramatically raises the risk of mid-air incidents. At these times, the risk is mitigated by listening to the CTAF with increased vigilance and making position reports. Also, ADS-B traffic is another major help. But remember: If there is a helicopter 500 feet above you, a water-filled bucket and cable may only be 400 feet or so away.

SAFECOM Reports

Just as the FAA pilot community has NASA Reports, pilots working interagency fire operations use SAFECOM safecom.gov. to process self-disclosed safety issues. Many of the reports relate to loss of separation, miscommunication and coordination issues among the aircraft and agencies working fires.

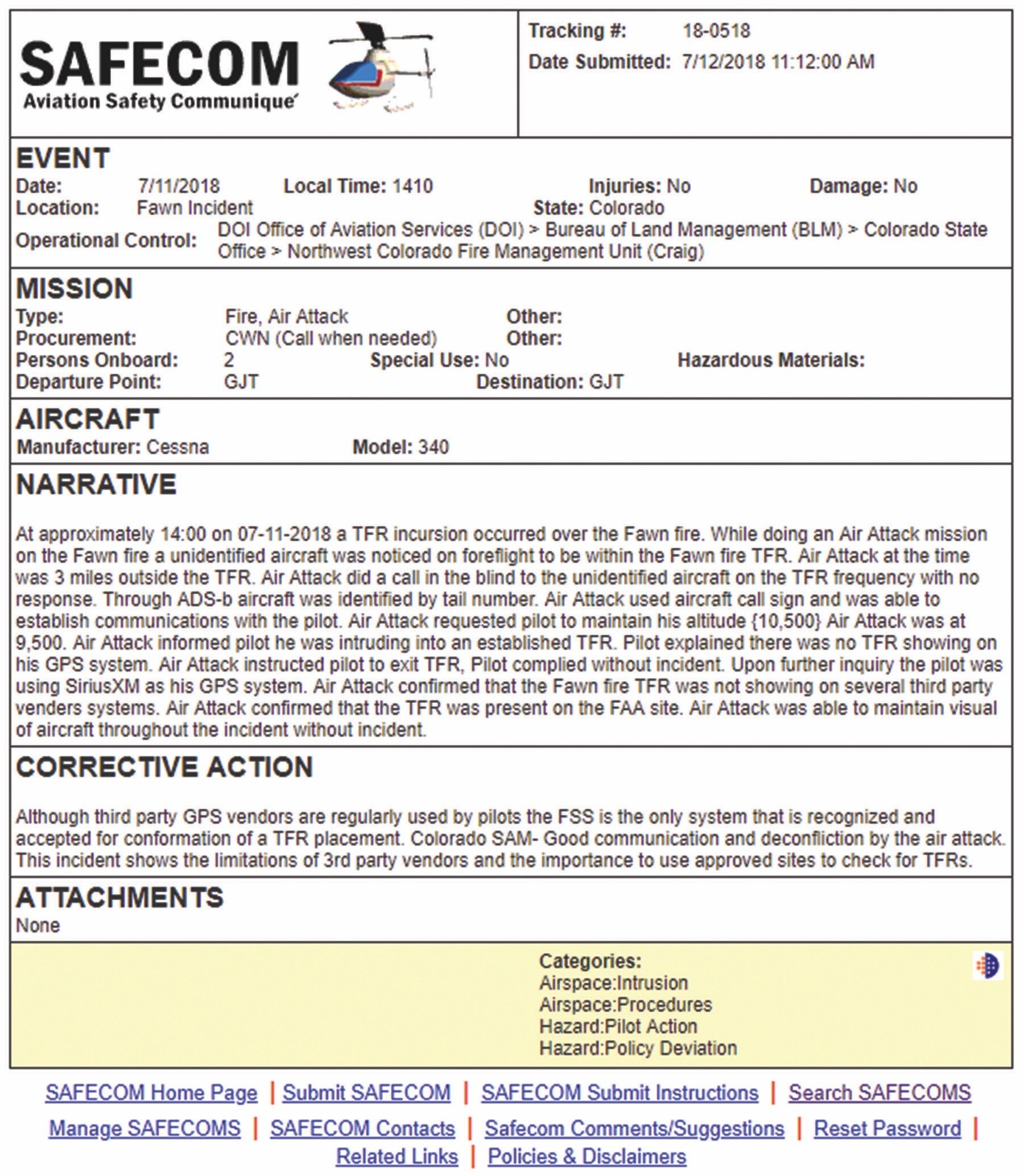

The big takeaway from my review of SAFECOM reports is that a common issue is intrusion into a TFR by unauthorized (i.e., general aviation) aircraft, often at altitudes conflicting with active firefighting operations. The frequency of this occurrence emphasizes why it is so important to use a device that reliably depicts current TFRs. The SAFECOM report above is an example illustrating the problems that occur with unreliable devices.

When it comes to TFRs, the burden of obtaining up-to-date TFR information is on the pilot. The FSS system is the gold standard for TFRs, followed by approved sites and, last of all, third-party vendors. All of this applies, of course, only when operating VFR. Right? Not necessarily: We also noted a SAFECOM report of an event involving a so-called SEAT—single-engine air tanker, typically a crop duster—which reportedly crossed an ILS final and generated a TCAS alert aboard a Delta Air Lines flight inbound to Hailey, Idaho.

Where there is smoke…

An active fire response can happen before there’s a chance to put up a TFR. U.S. Forest Service procedure is to establish positive control of the aircraft deployed against the incident as soon as possible, even before a TFR has been issued. The point is if you see a column of smoke, even if there is no TFR, behave as though there may be one, anyway.

There is a good chance aircraft are already on their way, and those aircraft are expecting other nearby aircraft to be communicating on interagency frequencies to deconflict their operations. If the column of smoke is in your flight path, you should expect aircraft orbiting said column to do recon, or perhaps dropping smoke jumpers, and perhaps aircraft nearer the ground dropping retardant. A TFR can pop up anytime there’s a large column of smoke.

Beware of Drones

Most of the time, I think concerns about colliding with a drone (or UAS—unmanned aircraft system—if you prefer) are a bit overwrought. Most general aviation flights are not in the “drone zone,” i.e., typically below 1000 feet agl. However, when it comes to fire operations, drone concerns are very real. Many different firefighting missions require flying at low level to manage equipment and personnel, and it’s the same level where voyeurs fly their drones hoping to get dramatic fire footage of retardant bombers dropping loads or firefighters rappelling from helicopters.

One of the first aircraft/drone collisions—on September 21, 2017—involved a U.S. Army Sikorsky UH60 Blackhawk helicopter and a DJI Phantom drone inside an active TFR near Hoffman Island, N.Y. It wasn’t a fire TFR, but it demonstrates that efforts to keep drones out of TFRs may not be effective. Drones are often spotted near active wildfires, sometimes solely because they are visually interesting. However, just as often, homeowners are desperate to learn whether their property has been consumed, and ranchers or farmers want to check on their stock or fields. Curiosity, unfortunately, can interfere with safe air operations during wildfires. When drones are sighted, as they increasingly are, many agencies will suspend aircraft operations, which only makes a bad wildfire situation worse.

Frequencies and Check-ins

When there are fire TFRs, it’s a good idea to use ATC’s VFR flight following, or go IFR. If that’s not feasible, most TFR narratives include both a telephone number and a VHF frequency for contacting the fire boss who controls the TFR’s airspace. If you plan on passing over the top of a TFR, or along its edge, consider calling in on the published frequency. Since fire operations involve numerous frequencies, let them know the frequency you are calling on. Since the published TFR frequencies are in the common aeronautical VHF band (as opposed to the FM bands more frequently used by interagency fire crews), chances are you will be responded to as “Calling in on Victor frequency.”

When I pass over the top of fire TFRs, I simply check in with the fire boss on the published frequency to let them know my location. Such check-ins are appreciated because it helps them deconflict your aircraft from other aircraft they are managing in the area, often just outside the TFR, and they’ll know your intentions.

Visibility issues

One additional consideration to be mindful of is how smoke can affect visibility. You may be within legal limits for visibility, but it is not uncommon for an unexpected smoke plume to quickly drop visibility to near zero-zero levels. When circumnavigating wildfire TFRs, have a general sense of which direction the prevailing winds will carry the smoke, then consider passing by on the upwind rather than downwind side. Doing so helps minimize any potential for getting lost in smoke.

Extra awareness, Please

Operating near wildfire TFRs definitely increases the number of hazards you’ll face, many of which are uncommon in more conventional airspace. There will be high concentrations of aircraft, both at low levels and at higher altitudes, and a mix of high- and low-speed, fixed-wing and rotary aircraft. There may be aircraft dropping retardant or carrying buckets on long cables, rappelers leaping from helicopters, smoke jumpers parachuting out of the sky, possible supply drops and sadly, the ever-present possibility ofdrone operators.

It sounds like a dangerous environment for a GA pilot, but for some perspective, it also describes most days at Oshkosh during EAA AirVenture. Those involved with firefighting operations have proven that good pilots who read the Notams will conduct themselves with heightened awareness and greater caution. That’s how to mitigate the operational hazards of the novel, though annual, wildfire TFR environment.

NARRATIVE

“At approximately 14:00 on 07-11-2018 a TFR incursion occurred over the Fawn fire. While doing an Air Attack mission on the Fawn fire an unidentified aircraft was noticed on ForeFlight to be within the Fawn fire TFR. Air Attack at the time was 3 miles outside the TFR. Air Attack did a call in the blind to the unidentified aircraft on the TFR frequency with no response. Through ADS-B, aircraft was identified by tail number. Air Attack used aircraft call sign and was able to establish communications with the pilot. Air Attack requested pilot to maintain his altitude {10,500}. Air Attack was at 9500. Air Attack informed pilot he was intruding into an established TFR. Pilot explained there was no TFR showing on his GPS system. Air Attack instructed pilot to exit TFR, pilot complied without incident. Upon further inquiry, the pilot was using SiriusXM as his GPS system. Air Attack confirmed that the Fawn fire TFR was not showing on several third-party vendors’ systems. Air Attack confirmed that the TFR was present on the FAA site. Air Attack was able to maintain visual of aircraft throughout the incident without incident.”

CORRECTIVE ACTION

“Although third party GPS vendors are regularly used by pilots the FSS is the only system that is recognized and accepted for conformation of a TFR placement. Colorado SAM- Good communication and deconfliction by the air attack. This incident shows the limitations of 3rd party vendors and the importance to use approved sites to check for TFRs.”

Mike Hart flies his Piper J3 Cub and Cessna 180 when he’s not schlepping people and their gear for an Idaho-based Part 135 operator. He’s also the Idaho State Liaison for the Recreational Aviation Foundation.