Light airplanes are fun. Light airplanes have style. They also tend to be expensive to own and operate. While we hold these truths to be self-evident, many pilots also labor to justify their love by pointing out that sometimes light aircraft can be decent transportation tools.

Airplane marketers have been eager to seize that attitude, labeling them time machines or personal airliners. Many pilots of high-performance singles and light twins have gone along for the ride – as much because they wanted to believe it as because it was true.

Its in this environment that some of the most preventable of accidents occur. Usually it involves experienced pilots who push the envelope of weather and loading, but other times its something as simple as not taking flight seriously enough.

Perhaps nowhere is the syndrome more evident than in watching a pilot make a preflight inspection. The logic seems to be, It worked when I shut down last time, so itll work now.

Such may have been the case with the owner of a Piper Malibu who was planning a flight from Hawthorne, Calif., to Las Vegas one sunny Sunday morning in May.

The pilot, with two passengers aboard, taxied to the self-serve fuel pump at 11:35 am and pumped 120 gallons of fuel into the wings, which were modified to hold 142 gallons instead of the stock 122. About 15 minutes later, he called the ground controller, reported he had the ATIS and was ready to taxi.

In less than four minutes, the pilot taxied more than 2,400 feet and called ready for takeoff. He was issued a takeoff clearance at 11:57, and he and the controller exchanged a few collegial personal words. The airplane lifted off of the 4,956-foot runway at 11:58.

Witnesses at the airport described the airplanes takeoff run as far longer than normal. The engine throbbed, though it was not sputtering. The witnesses all described the sound of the engine as not right.

Those who saw the initial climb reported the climb gradient as very shallow, and radar data indicated the Malibu crossed the airport boundary near the departure end of the runway at only 145 feet, with an airspeed of about 82 knots.

When the airplane was more than a half-mile from the airport boundary, it had climbed to 400 feet msl – about 340 feet above the ground.

In the airports urban environment, several people took note of the cabin-class single flying low over their heads. People on the streets heard the engine sputtering and popping. Some watched in both horror and fascination as the airplane banked steeply in an apparent turn toward the airport.

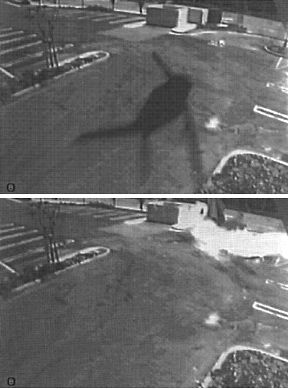

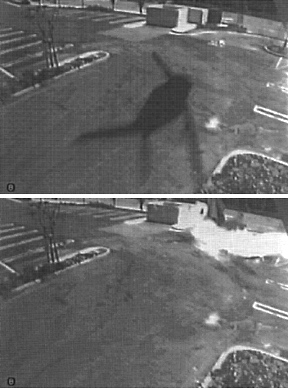

The Malibu began to turn about a half-mile from the airport when the pilot cranked in a left bank that all witnesses agreed exceeded 45 degrees. It had nearly completed the 200-degree turn when it apparently spun to the ground, crashing into the parking lot behind a Taco Bell.

The airplane burst into flames and would-be rescuers were hindered by two secondary explosions. All three aboard perished.

Long Layoff

Accident investigators determined the pilot had not flown the airplane in more than five months. During that time, the rainy season in Southern California, it was parked at an outside tiedown with only 10 gallons of fuel in each wing.

The pilot had owned the airplane for nearly a decade, logging some 1,250 hours. His total time was uncertain. He reported 1,990 hours on his medical certificate application a year earlier but 2,550 on his insurance policy application.

The pilot took annual recurrency training from a former instructor in Pipers factory training program, who described him as a good, safe pilot who used good common sense and good pilot technique.

The damage caused by the crash made analysis of the accident scene difficult, but the wreckage did give some clues as to why the airplane may have crashed, but also raised some questions.

The landing gear actuators were found in the extended position and the flap actuators showed the wing flaps were about 7 degrees down. Those two indications are correct for a takeoff scenario, but raise the question of why the pilot did not eliminate their drag when faced with the airplanes poor climb.

The fuel selector was found in the off position, with the selector firmly in the detent. The positions of all components in the fuel valve system were consistent with the fuel being switched off, raising the possibility that the pilot had taken off with the fuel shut off.

Investigators then determined that the airplane would supply only about one-third of a gallon of fuel to the engine with the valve off. However, the minimum fuel deemed necessary to start the engine, taxi and take off would be 3.0 gallons.

That raises the question of why the fuel selector was off and how it got that way. That question was never satisfactorily answered.

Although the engine components did not show any obvious signs of pre-impact failure, one cylinder was sent to the Continental factory for analysis, although the NTSB file is unclear why the part was suspect. However, Continental admitted losing the cylinder after delivery and it was never examined.

Where Error Lies

With no smoking gun, fell back on two points: the long period of inactivity and the turn back to the runway.

Even though it did not demonstrate any evidence to support the conclusion, investigators blamed partial loss of power due to water contamination in the fuel system and the pilots inadequate preflight inspection, which failed to detect the water. While that may be true, there was no evidence that points to that conclusion.

The Malibus Continental powerplant has long been the object of suspicion for its reputation for coming apart at the seams. This particular engine had about 1,100 hours since overhaul. It had gotten overhauled cylinders about 350 hours earlier and, at the previous annual inspection, one cylinder had been overhauled again. This history of engine woes, not unique among Malibus, shows that power failure can occur without water in the fuel.

The pilot could have preflighted the airplane extensively before taxiing to the fuel pumps. He was at the pumps for 15 minutes, and at 24 gallons per minute the fuel pump could have delivered full tanks in only five minutes.

While the taxi to the runway appeared rushed, the pilot may have considered his inspection and runup done and thought he was just being efficient.

Second, the investigators cite the failure to maintain a sufficient airspeed margin above the stall during his steep turn back. However, they cite the airplanes radar-derived groundspeed of 82 knots and the airplanes 82-knot stalling speed at a 45-degree bank with gear and flaps retracted.

However, the wreckage suggests the gear and flaps were extended, which would lower the stall speed. The uncertainty in all this, of course, is just how steep the bank was. At a 60-degree bank, the airplane would have stalled even with the flaps all the way out.

Another factor the investigators cited was the brief personal conversation between the pilot and the tower controller, which the NTSB contended was a distraction that prevented the pilot from detecting the partial power on takeoff.

See for yourself. The conversation, in its entirety:

Tower: …cleared for takeoff.

Pilot: 7YV on the roll.

Tower: And by the time I get off, Andrew, youll be touching down.

Pilot: You should have told me. I might have waited for you.

Tower: Next time.

Pilot: OK.

While it seems unlikely such a brief exchange could have been a substantial diversion, clearly the pilot did fail to respond to the sounds and performance that, by all accounts, were far from correct. Factory specs call for the airplane to take off in 1,760 feet and climb at 800 to 1,140 fpm at 110 knots.

With 5,000 feet of pavement, the pilot had plenty of opportunity to detect the lack of power and abort the takeoff. Why he didnt will be one of the enduring mysteries of this episode.

Because it was his personal airliner? His hassle-free way to beat the airlines at their own game?

Perhaps, in his mind, thats exactly why.

-by Ken Ibold