Circling an airport after an instrument approach procedure (IAP) to land on a runway other than the one aligned with the IAP is something all instrument-rated pilots have practiced. It’s a maneuver that places an airplane relatively close to the ground—sometimes at half the traffic-pattern altitude—and can require steeply banked turns.

Of course, steep banks close to the ground are an invitation for a stall-spin accident when the vertical lift component is traded for the horizontal. Since circling is usually performed in poor weather, it can be a busy time: In addition to keeping the airport and intended runway in sight, pilots must also maneuver the airplane at a relatively low speed. Of course, slow airspeeds, steep banks and low altitudes are the recipe for fatal stall-spin accidents. There just isn’t enough altitude to recover.

Some airplanes circle to land after completing an IAP better than others; slower usually is better. The basic issue is the turning radius required to keep the field and intended runway in sight. If the required turn results in a steep bank, the airplane’s stalling speed increases. Too often the stalling speed rises to eclipse or exceed the airspeed being flown. Even if it doesn’t, airspeed margins above stall are reduced to the extent there’s no “cushion” remaining for turbulence, or a misconfigured or mishandled airplane.

Additionally, a pilot’s normal visual references can be dramatically altered when circling. The poor weather is one complication but the low altitude presents a different sight picture to the pilot, one with which he or she might not be familiar. The result can be controlled flight into terrain short of the runway, even though things looked like they always do.

Background

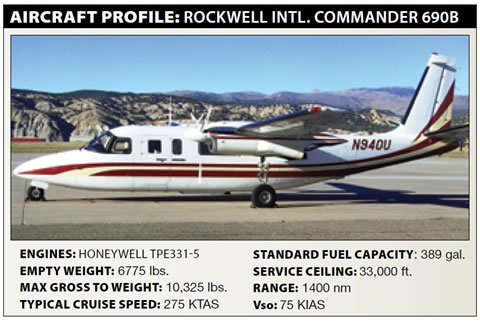

On August 9, 2013, at about 1121 Eastern time, a Rockwell International 690B was destroyed after impacting two homes while maneuvering for landing in East Haven, Conn. The commercial pilot, one passenger and two people on the ground were fatally injured. Instrument conditions prevailed.

At 1104, ATC advised the pilot to expect the ILS approach to Runway 2 at the Tweed-New Haven Airport (KHVN) in New Haven, Conn., with a circle-to-land maneuver to Runway 20. At 1115, the flight was cleared for that approach. At 1116, the pilot reported 7.5 miles from the ILS’s final approach fix and was instructed to report a left downwind for Runway 20.

At 1119, the pilot reported the left downwind and the controller cleared the flight to land. At 1120:51, the pilot reported visual contact with the airport. No further communications were received. The last recorded radar target was at 1120:53, about 0.7 miles north of the Runway 20 threshold and indicating 800 feet msl.

Investigation

The airplane came to rest inverted with about one-half of the cockpit and fuselage inside a house and basement due north and approximately 0.6 mile from Runway 20’s threshold. After the accident, a controller stated he observed the airplane at midfield on a left downwind for Runway 20 and that it was “skimming” the cloud bases. The controller lost visual contact with the airplane, but about two to three seconds later it reappeared nose-down, rotating counterclockwise and descending from the clouds to the ground. Other witnesses reported seeing the airplane descend in an unusual attitude and/or the sound of loud engine noise just before impact.

All major components were located at the accident site. Control cable continuity was confirmed from the elevator and rudder to the cockpit area. Due to impact and thermal damage, aileron control cable continuity could not be confirmed. The nose landing gear was in the down-and-locked position, as was the landing gear selection handle. The right wing was destroyed by thermal damage. The left wing impacted the ground and was separated from the fuselage. The left main landing gear remained attached to the wing, and was in the extended position. Wing flap position could not be determined.

Teardown examination of both engines did not reveal any pre-impact mechanical malfunctions or anomalies that would have precluded normal operations. A detailed examination of both propellers also did not reveal any pre-impact mechanical malfunctions or anomalies.

Recorded weather at KHVN, at 1126, included wind from 170 degrees at 12 knots, gusting to 19 knots, visibility nine miles in light rain, and an overcast at 900 feet.

Radar data indicate the airplane flew as close as 1800 feet east of the approach end of Runway 20 on the downwind leg of the airport traffic pattern. That close to the runway would require an approximate 180-degree turn within a radius of 900 feet to align with it. At the last airspeed approximation from the radar trajectory of 100 knots, the airplane would have had to bank about 45 degrees to complete the turn (assuming a consistent bank throughout the turn and not accounting for the tailwind); however, the airplane’s stall speed at that bank would increase to 88 knots in the landing configuration or 94 knots with flaps retracted. The stall speed would increase beyond 100 knots as the bank increased beyond 45 degrees. The sidebar on the opposite page has additional details.

At that time, the airplane was at 600 feet msl and the controller queried the pilot if he could maintain visual contact with the runway. The airplane then climbed to 800 feet into the clouds, before reappearing in a nose-down descent. The minimum descent altitude for the ILS Runway 2, circle to Runway 20, was 720 feet msl.

Probable Cause

The NTSB determined the probable cause(s) of this accident to include: “The pilot’s failure to maintain airspeed while banking aggressively in and out of clouds for landing in gusty tailwind conditions, which resulted in an aerodynamic stall and uncontrolled descent.”

Although the ceiling was low, good visibility underneath was being reported. The pilot could have widened out his pattern, precluding the need for a steeply banked turn to align with the runway. Additionally, he may not have reverted to the flight instruments when he lost visual reference as the airplane re-entered the cloud base. Being so close in and then losing visual contact, a missed approach would have been preferable to attempting a steeply banked turn with so little altitude beneath the airplane.