Of all the hazardous attitudes displayed by pilots, one rarely written about is our drive to be efficient. Despite how much we love flying, we are always looking for efficiencies to exploit and make the best use of our time and resources. I think it’s also true that aviators often are strongly driven individuals, perhaps more so than non-aviators. It takes drive to become a pilot and an excess of drive to earn multiple ratings.

The drive to be efficient manifests itself in a variety of ways, some no doubt familiar, but it is clear that it is an attitude that must be tempered and offset by conscious risk management. Understanding the areas where we may be trading risk for efficiency will make us better and safer pilots.

Flying Direct

The advent of the direct to GPS button, which allows us to fly a straight line between two points, was instant gratification for efficiency-loving pilots, especially since IFR flights no longer needed to fly inefficient tinker-toy flight paths connecting VORs as long as ATC cooperated. But instant gratification also came with instant risk tradeoffs. The biggest of them is not obvious until you look beneath the magenta flight path where there might not be many, or any, airports.

I often considered this tradeoff when I chose to punch “Direct” between my former hometown of Idaho Falls, Idaho, and my frequent destination of Richland, Wash. Flying direct took me over Central Idaho’s mostly roadless and vacant mountains and canyons. My other option was to fly a much longer, more conservative route following the interstate highways and mostly developed agricultural lands and cities. The longer route with more roadways and airports below added almost an hour to an otherwise three-hour direct flight. It was not efficient, but when weather was marginal or the night was moonless, I knew the scattered city lights along the interstate would make the extra hour more comfortable. More lights, more cities, more roads and more options.

There are times, however, when taking a direct path makes more risk-management sense, even if there are fewer airports below. A shorter flight is less taxing, so it contributes less to fatigue, which should always be a consideration on any long-duration flight. Going direct might get you home before nightfall. It might also allow you to stay ahead of changing weather.

Most of the continental U.S. is more populous than Idaho, but there are still plenty of flight paths that are devoid of major cities and airports or have similarly inhospitable terrain. Areas like the Mojave Desert, the Great Lakes or the cyprus swamps of the South are particularly unfriendly for off-field landings. The challenge of flying direct is balancing the efficiency benefits against the known safety liabilities.

Multi-Variate Problems

It is not uncommon to take a nerdy pride in finding the most efficient altitudes as winds aloft shift along our course. But to be maximally efficient, there are often risk-management tradeoffs. For example, if we fly lower to avoid headwinds, we may also be reducing our opportunity to reach an actual airport if an engine quits. The sidebar on the opposite page helps demonstrate how altitude affects gliding distance.

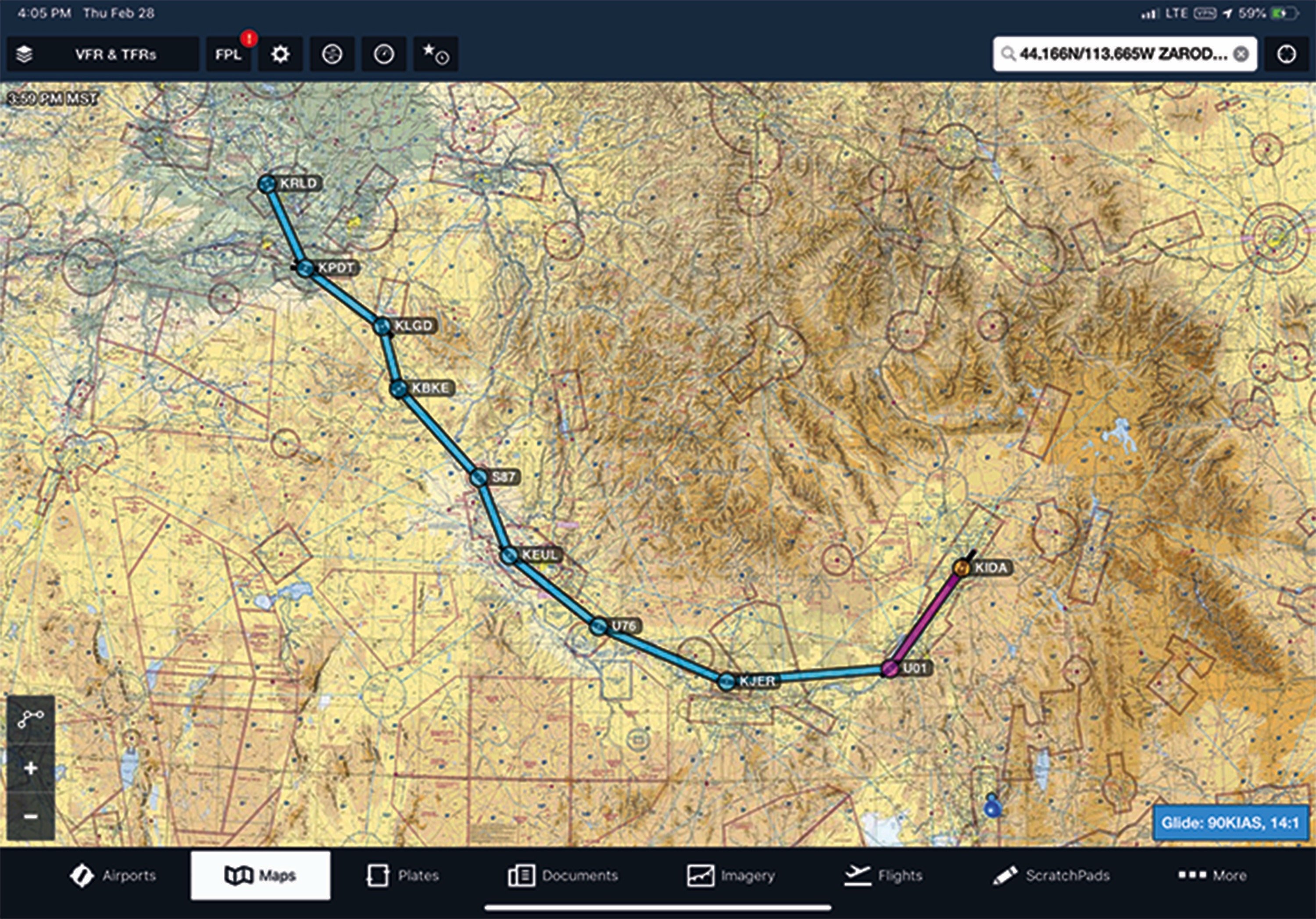

Before simply punching “direct to” for efficiency, I suggest you look at the distribution of airports beneath the direct path. Perhaps you can tack a bit north or jog a bit east—some option where you can always have an airport within gliding range, or nearly so. Preflight rubber-banding (see the sidebar “Rubber-Banding”) is always a great idea. Chances are the bit of dodging and weaving you plan in advance will add little to your flight time. At the same time, you’ll benefit by adding significant safety margins.

Night Flights

Like many other professionals, I found it most efficient to end my day with an early-afternoon meeting. Departing for home directly afterward provided me with immediate savings on hotel expenses and out-of-town meals, and allowed me time to brief weather, preflight the plane and head home before dark. At the same time, it also frequently meant some portion of the flight would be at night. As a pilot, there were upsides, especially the ease of keeping up my night currency and a greater proficiency at night cross-country. I learned to love the smooth night air compared to bouncy afternoons. The downside, of course, was that I exposed myself to much greater risk.

Night flights are definitely more hazardous than day flights. If you don’t agree, try pulling the power to simulate an engine failure and imagine what it would be like at night. It should not be surprising to learn that a daylight event, which can resolve to a mere incident, often becomes a full-blown accident by night and is accompanied by higher lethality rates.

There are several contributing factors for the greater number of nighttime accidents. Controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) is the biggest contributor. If you can see something easily, you are far less likely to fly into it. Spatial disorientation is also far more common at night than during the day. Finally, to state the obvious, there is simply a lack of natural light. Not only is the lack of daylight a known contributor to sleepiness, odds are that your night flight falls at the end of a typical day of activity. Without additional rest, the body’s circadian rhythms kick in.

If your preflight planning involves a night flight to gain efficiency, know that it comes with a marginal risk management price.

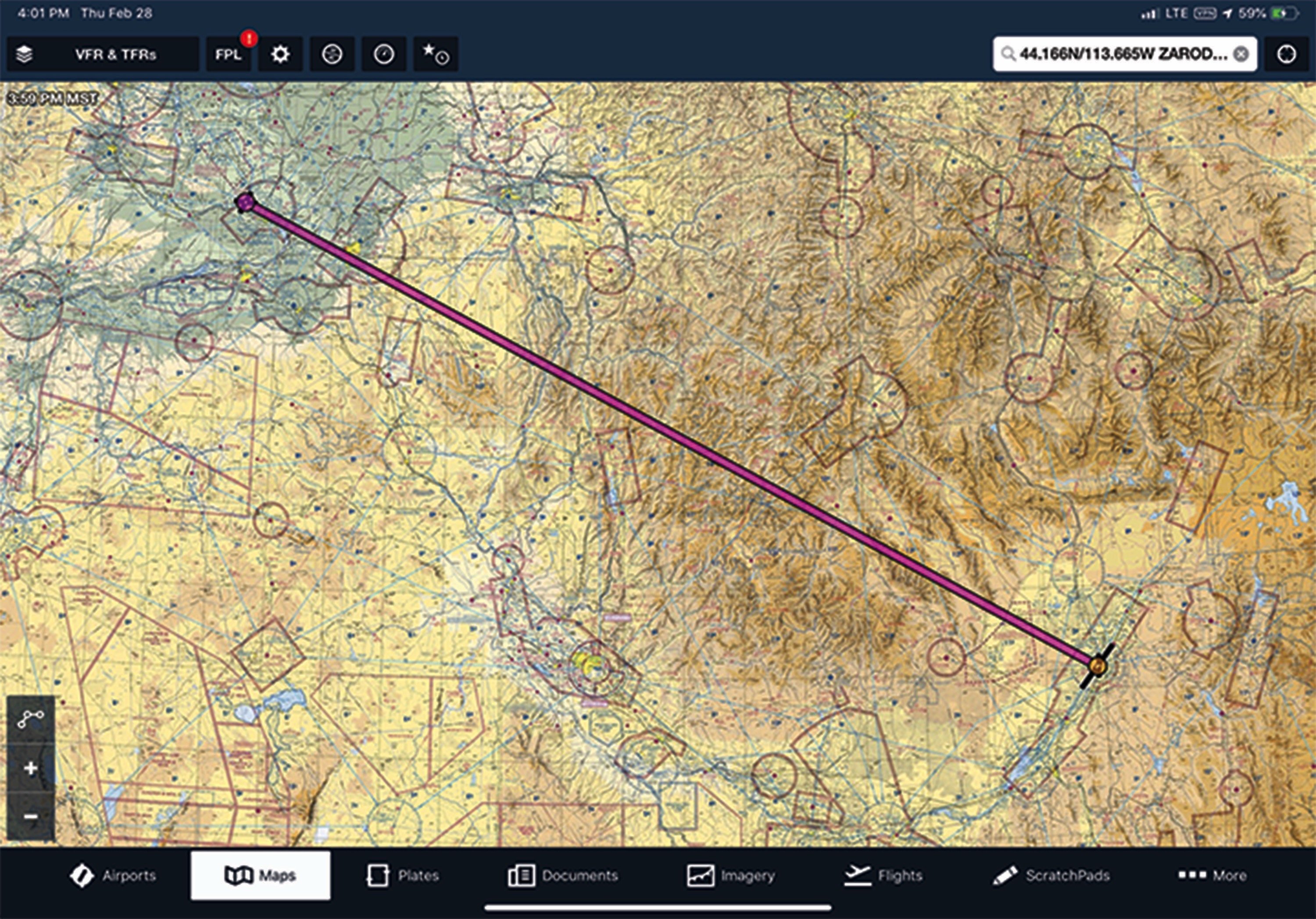

During preflight planning, you can draw a direct line from point to point and then edit the flight path to fly closer to optional airports. If you use an electronic flight bag program, you’re in luck—many are capable of “rubber banding” the flight legs. To do so, touch the leg and then drag it to VORs, airports or fixes to pick the flight path that maximizes the number of airports along your route. Below, we did that with a proposed flight from Idaho Falls Regional (KIDA) to Richland, Wash. (KRLD). The direct path (top) has seven paved airports within 10 nm compared with 30 (bottom). Depending on the EFB you’re using, other tools may be available, including those designed to consider gliding distance.

CheapGasitis/Getthereitis

Pilots who train their eye on the cheaper fuel at the next airport are often victims of cheapgasitis, as I wrote about in Aviation Safety’s May 2014 issue May 2014 issue while describing part of a trip to Oshkosh, Wis., for the EAA AirVenture Fly-In. There is nothing wrong with a bit of planning to save money, except if you are one of those pilots tempted to stretch your fuel reserves past safe limits. Running the tanks dry in an ersatz pursuit of monetary efficiency should be one of the more embarrassing accidents, but it still occurs with regularity.

The pursuit of efficiency is also frequently at the root of getthereitis, the drive to reach a destination, sometimes at any cost. A pilot that indulges in getthereitis usually rationalizes the benefits of arrival at the destination and trades away safety margins. The danger of pursuing efficiency as an end in itself is that it can undergird rationalizations that actually involve taking on risk in the name of reducing it. A hypothetical NTSB report illustrates this:

“To avoid staying an additional night (to save money), the pilot chose to depart in the evening (accepting a nightlight). A cold front was forecast to arrive the following day that would bring unstable weather below VFR for the subsequent three days. To stay ahead of the weather and take maximum advantage strong tailwinds, the pilot skipped the evening meal and drove directly to the airport. To optimize his remaining daylight, the pilot performed the preflight while receiving a weather briefing, did not file a flight plan and accepted an intersection departure….”

This hypothetical is a good object lesson in the need to evaluate decisions from a transactional risk-management perspective. While many choices appear to be determined in the interest of safety—staying ahead of weather, optimizing departure time to take advantage of tailwinds, maximizing remaining daylight—there are tradeoffs with not eating, departing late and multi-tasking the briefing with the preflight. Overall, this hypothetical pilot’s actions appear to be driven by the desire to optimize efficiency in the flight itself, in safety and in time. But when you consider the tradeoffs, it isn’t clear they are weighted equally.

Efficiency, Risk Tradeoffs

Nearly every private pilot on a multi-day or long cross-country flight has to face risk tradeoffs in the interest of efficiency. When I flew to Oshkosh, my planned fuel stops were designed to optimize winds aloft, airport hours and fuel prices. When I followed my plan, my preplanned route provided optimal efficiency. When the weather changed and a thunderstorm built over the planned fuel stop, my plan to gain efficiency became a risk-management liability.

I have chosen to fly at night to get ahead of a weather system. When I do, I am buying the cost of exposure to an unknown weather system and adding it to the known cost of the hazard of flying at night. If I am neither night current nor instrument current, the purchase is not available. But if I am, I still have a choice. I can choose to accept or not.

I have gone both ways. In the air and realizing that I am getting tired, I have flown “direct to” and accepted having fewer airports below me knowing that I would arrive an hour earlier, thus reducing my exposure to night flight and fatigue. I have also chosen to drive, stay an extra week, leave my plane at the airport and rent a car, and sometimes chosen not to take the trip at all. With these latter choices, I gave up on efficiency entirely. Sometimes you simply cannot optimize the equation for safety and risk reduction without having a healthy no-go option at the ready.

Efficiency is very important to companies trying to make a living with airplanes. Whether they are transporting passengers or cargo, the commodity they are selling is time. While it sounds trite, that commodity is worthless if it isn’t delivered safely. Businesses have to be efficient to succeed, and pilots like me are driven to make it happen. But safety always comes first.

Especially when dealing with less-than-ideal weather, in mountainous terrain or when flying a single, night operations by definition are transactional: The risk of flying the route at night is greater than in daytime, presuming there’s a choice. So how do you cope?

Fly IFR

If you’re rated and current, fly the route IFR. Except in very remote areas, you’re probably in radar and radio coverage, and if you stay on airways at or above the minimum en route altitude, you’re guaranteed not to hit anything. Use the destination runway’s glide path.

Thorough Preflight Planning

Not only should your preparations include flashlights, landing lights and instrument-panel lighting, but—more than ever—you need to think about divert airports. Changing your route is one option, but even that won’t do much good if you don’t keep track of what’s closest and what you need to do to get there.

USE Oxygen

The benefits of breathing supplemental oxygen (O2 ) at night are well-known: reduced fatigue, clearer thinking and better vision. We recommend considering supplemental O2 at night when at or above 5000 feet msl. Here is another tradeoff: Supplemental oxygen contains very little moisture, so you might want to hydrate. And you know what that means. —J.B.

Consciously Efficient

Will an intersection takeoff save time? Sure. But am I really gaining that much efficiency? Sometimes yes, sometimes no. When the 737 in front of me is told it will be 10 minutes before it can be cleared for departure due to metering at the destination airport, accepting an intersection takeoff might take 150 feet off a 9000-foot-long runway and buy me 10—15 minutes. On the other hand, if I am simply too lazy to taxi another 2000 feet to buy the full length of a 5000-foot strip, it would be a fool’s choice.

The choices we make to maximize efficiency aren’t necessarily right or wrong as long as we are consciously aware that gaining efficiency may be at the expense of additional risk. If we consciously choose to “buy” a bit less headwind by flying lower, we should also understand it comes with a “cost”—reduced gliding options. A conscious choice empowers us with the knowledge that we made that choice while understanding what we traded away in exchange.

The pursuit of efficiency should never drive bad decisions. Making a conscious choice empowers us to reverse our choice, to give up a bit of efficiency in exchange for a bit more safety margin. Climbing 2000 feet higher may add 10 more knots of headwind and might add 15 minutes to a long cross-country, but if the engine quits, it provides a few extra minutes and nautical miles of options.

A driven pilot needs to have a questioning attitude and a transactional view of the risk mitigation options. The most efficient outcome for a driven pilot is taking off, flying and landing safely. It is just that simple.

Mike Hart is an Idaho-based passenger, cargo and backcountry pilot. He also is the Idaho liaison to the Recreational Aviation Foundation.

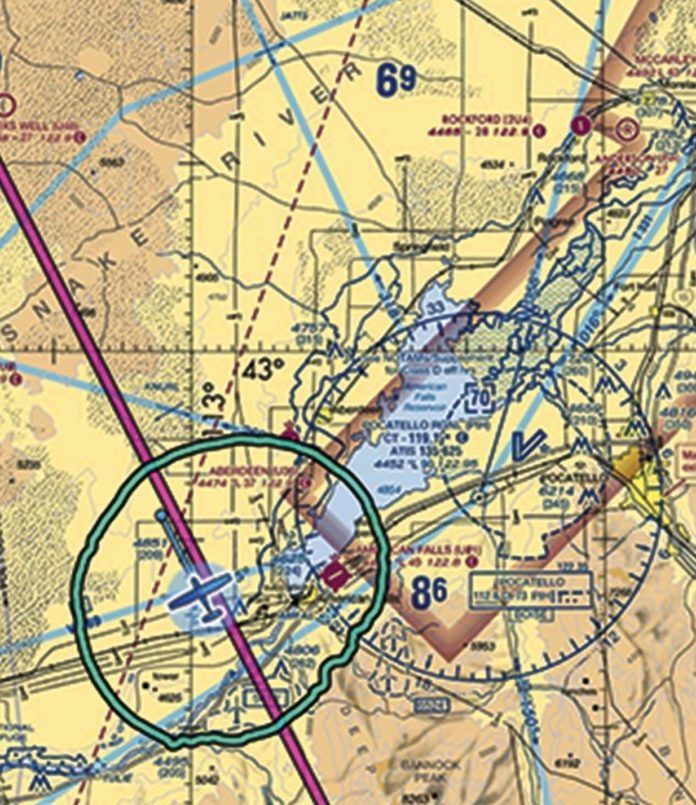

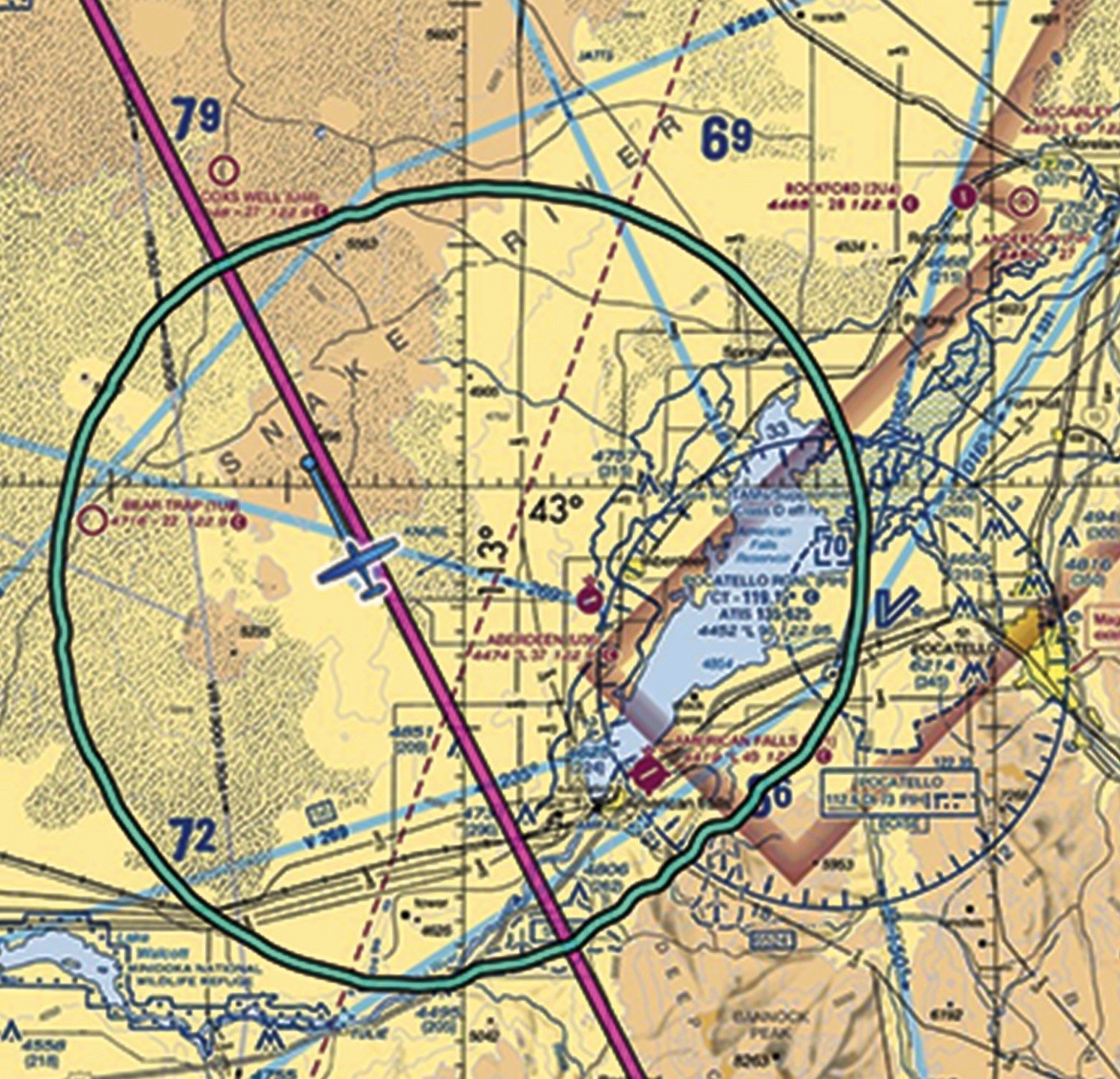

Many electronic flight bags—like ForeFlight, shown here—can estimate your airplane’s potential gliding distance given your altitude above ground and forecast winds.

Here, that capability is used to emphasize that higher is better, at least when it comes to gliding distance. Potential landing areas are within the green circle, which enlarges as the airplane climbs from approximately 3800 feet agl (left) to about 7500 feet (right).