The ducks were going to be walking soon. It was sometime in the early 1980s-I had just flown my rented Skyhawk down to the ILS Runway 5R minimums at the Raleigh-Durham (N.C.) International Airport (RDU), breaking out at decision height. Earlier, I missed the 600-foot minimum descent altitude radar approach at the nearby Horace Williams Airport at Chapel Hill, N.C. This was Plan B. After discharging my passenger-her car was at Chapel Hill, but there was no way for me 288 to get her there-I was on the phone with Flight Service, trying to figure out how to get back to the Washington, D.C., area that night. The briefer was clearly overworked; everything on the east coast was down the tubes. An Army King Air crew, destination unknown, was securing their steed for the night; others were making rental car and hotel reservations. The briefer had no good news: The D.C. area was above ILS minimums, but not by much. The problem became which airport to use for a legal alternate. Nothing with which I was familiar-or where I wanted to spend the night-was looking good. I asked the briefer, “What are other people filing?” His quick response sealed the deal: “Savannah or Tri-Cities.” There was no way to flog that Skyhawk from RDU to D.C., miss an approach and then get to eastern Tennessee without airborne refueling. I was walking, too. Using one of todays Internet-based weather resources, how could I get that alternate-airport information, as succinctly and quickly, as the briefer offered up? Not. Going. To. Happen. Technologys Wonderful Make no mistake, the information technology revolution over the last 15 or so years should share responsibility for the excellent safety record all segments of civil aviation have achieved. A substantial portion of that safety improvement has its roots in the proliferation of high-quality weather and flight-planning information, as well as eye-popping graphics displaying everything from infrared satellite images to icing forecasts and to winds aloft. Like you, maybe, most of my pre-flight briefings these days start at a computer. Ill either run an automated Duat session using one of the available front-ends or log onto a free aviation weather site. My immediate concerns are the overall weather picture along my route, whether there is any severe weather like icing or thunderstorms, the winds aloft and the ceiling/visibility at my departure and destination points. If those basic parameters are good and theres no reason to investigate further-like anomalous observations or forecasts, a frontal system moving in or Airmets/Sigmets for the route-Ill usually complete my pre-flight planning in that sitting. If there are some questions or concerns, Ill dive down deeper into the data Im looking at, check other sites and products-like graphics-and then make some decisions. Decisions, Decisions The first decision is whether to go at all. Part of this one is the overall need to make the trip, or make the trip

288

known to take a nap on the FBOs couch, waiting for a thunderstorm line to blow through-can make the difference between a wild ride, a trashed cabin and a diversion or a smooth flight in just-washed air. Ive rarely found a situation where a delay of 12 hours or so hasnt seen much-improved conditions.

Another decision is which way to go. Back in the days before we both got our Instrument ratings, a buddy and I once spent an entire holiday weekend grounded in Washington, D.C., instead of enjoying our hotel reservations in Key West, Fla., because we were too stupid to fly west around an area of low ceilings and visibilities. We still laugh about that weekend-hes now a captain for “a major airline”-but the lessons remain.

First, its always safer to cancel the flight, no question. Second, if youve got the time and fuel, and the weather at your departure and destination points is good, theres usually a way to get around the bad stuff. Unless you must fly a certain route, investigate alternatives, especially if the two routes terrain is about the same.

Finally, if I go, Ill continually update both my weather and my original “go” decision. Once airborne, my eyeballs have just become my primary source of weather data. If I dont like what I see, or if I have some questions ATC or Flight Service cant answer, Ive been known to land, refuel, re-group and re-brief. Only on rare occasions has such a diversion resulted in being forced to overnight somewhere, but even those times turned out well.

What About Interpretation?

I mostly do my own interpretation these days, but I didnt start out that way. While its relatively easy to read and understand a Metar saying “00000KT 10SM OVC45 01/M02” versus one that reads “30024KT 01SM OVC03 01/01,” newer pilots may not readily grasp the difference a few numbers can make. But thats the tip of the iceberg when it comes to interpreting more complicated data, especially after checking weather a few times in search of the mythical severe clear and finding that it

keeps changing!I remember the first time I managed to make the automation gods cooperate and downloaded my first weather data from CompuServe over a 300-baud acoustic modem, back in the early days of personal computing. All of a sudden, I was bombarded with a textual gobbledygook trying to impart information. Instead, it only succeeded in confusing me. I found myself looking at weather data I really hadnt seen since studying for my previous FAA written exam, and I was rusty. Ive gotten much better at it since then, but the underlying interpretation issues remain.

The other issue is a newer pilot may have only flown on “good weather” days. When it comes to a visceral understanding of the difference between “10SM OVC45” and “05SM OVC15,” they may never have seen it before and, consequently, cant comprehend. Importantly, weve never seen an automated weather briefing that includes the phrase, “VFR not recommended.”

The thing about interpreting weather information, especially the textual kind, is trying to relate it to what one will see through the windshield. Thats another reason experience counts-get out there and fly-and where the newer pilot may need some help.

That help is best when it comes from a CFI or pilot-friend who knows the pilots training and experience level. Its usually a bad idea to eye your barely-IFR Skyhawk while you wait out some weather, then ask the Learjet jock who just landed after an ILS to minimums about the weather he encountered because he has no clue about your skill level and what youll find acceptable or unacceptable.

The flip side of this coin, of course, is that when youre asked in the pilot lounge about the weather you just survived, ask a few questions about the pilots equipment, ratings and equipment before answering. Try to tailor your response to his or her apparent skill level and apprehension. Youre never wrong if you suggest he cancels his planned flight and regroup tomorrow.

Is This Stuff Current?

Where you get your weather is just as important as

when you get it. Obviously, we wouldnt want to base a go/no-go decision for todays 1000-nm flight on data we picked up yesterday afternoon. Similarly, we wouldnt want to depend on the local television weather babe to help us pick our way through a squall line an hour after the evening newscast.Of course, each full Metar, Pirep and area forecast-among other weather products-carries a time stamp of some sort, advising when the data was observed or when the forecast was prepared and for how long it is current. Various “official” weather graphic products like prog charts also carry a date/time stamp. From this information, its easy to determine if our data is current.

With some weather data, however, its tough to separate the current material from the dated. For example, I use the Weather Channels Web site

Ultimately, theres a reason the FAA has spent so much time and treasure on collecting and disseminating weather information. Dont depend on a boating or agricultural forecast for your weather needs. But you knew that.

Pretty Pictures

Text-based data is necessary and useful, especially when trying to decide if the destinations weather will require filing an alternate airport-and which to choose. Its also an easy-to-interpret format, most of the time, and easy to compare. But the real value of self-briefing by using an Internet-based aviation weather service is the pretty pictures. Even 10 years ago, we didnt have close to the cool stuff we have now.

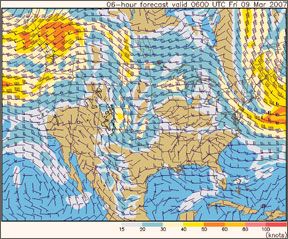

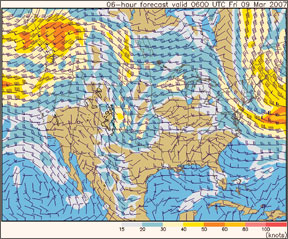

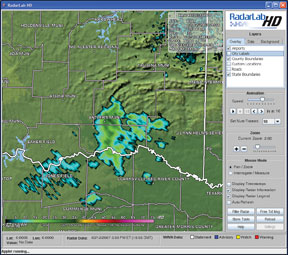

Pick a severe or even benign weather phenomenon and theres likely a specialized weather graphic available to describe it. Examples include forecast icing potentials, winds aloft and turbulence. My “favorite,” especially in summer months, is Nexrad weather radar. The various Nexrad sites around the country all feed their graphical data into the NOAA/NWS site (see the sidebar on the opposite page), allowing me to pick and choose the most appropriate red splotches to view. I can zoom in and out, play a looping video of recent echo movement, discern tops and velocity, all in the comfort of my home office.

But the real value of these weather graphics is the detailed snapshot they provide. Its a lot easier to visualize, say, the winds aloft impact on various proposed altitudes when a mouse click is all we need.

When In Doubt, Call

Funny thing: I can click “refresh” on my computer all day long and, if the weathers down the tubes, itll stay down the tubes. Wishing for better weather to get that important business trip out of the way or complete the holiday flight to Grandmas house wont make it so. When I was younger and stupider, Id sometimes just turn off the computer, drive to the airport, climb in the plane and go when I didnt like the answers I was getting. Somehow, I survived, in spite of myself.

For probably 90 percent of my flight planning needs, I dont need to pick up the phone and call Flight Service. The remaining 10 percent involves finding myself at an out-of-the-way airport lucky to have cellphone service, much less a broadband connection to the Internet, or when I have a question.

As I related at this articles beginning, there are some things we just cant depend on alphanumeric or even graphical weather data to tell us, or which simply takes to long to uncover. Too, there may be an error in the online data, a facility outage or a Notam we dont understand. Thats when its best to pick up the phone to call Flight Service and ask.

Is Internet-based weather the best thing since canned beer? You bet. But sometimes I want something else, something more than what I normally use. I can surf to a different site offering different graphics and sometimes that helps me make the decision. Dont be afraid to use Internet sites to obtain your weather information. Feel free to pick through them and find the ones you like best, or plunk down a credit card to access the services airlines and corporate operators use.

But there will be a time when thats not enough, when you cant make sense of a Notam, or when you simply dont understand why one station is reporting good weather and everything else nearby is down the tubes. Thats when you pick up the phone and call Flight Service. If it was good enough 30 years ago, its good enough now.