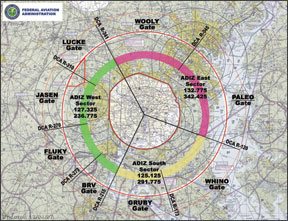

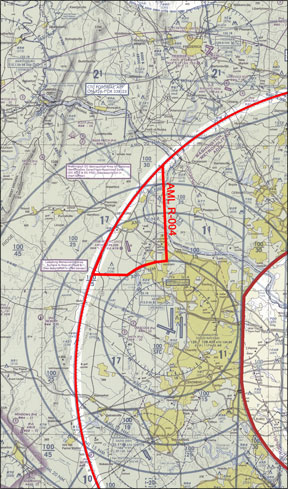

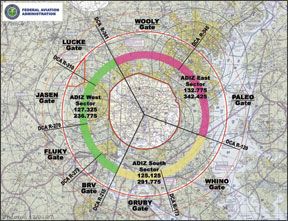

Airspace designations, along with what is and isnt permissible inside specific areas, are perennial sources of frustration and confusion among pilots of even considerable experience. Once ones understanding develops beyond the different classes and past special use airspace, theres always the issue of how to deal with airspace in which more and different rules or procedures apply. In recent years, special flight rules areas, SFRAs, have been created to ease the flow of traffic and prevent unsafe 288 conditions at the Grand Canyon and at the Los Angeles International Airport (LAX). The dimensions, rules and procedures for these areas are clearly documented in various places, including FAR Part 93, the FAAs Airport/Facility Directory and the respective visual charts. (Its always helpful, of course, to ask local pilots about any tricks they may know or additional information necessary to safely operate in these and similar areas.) Meanwhile, two additional SFRAs were created recently-one over Washington, D.C., and the other at New York, N.Y. Both were created in the aftermath of significant events and demand pilots planning to operate in or near them become familiar with their requirements. Thankfully, appropriate training is available for both and, in the case of the Washington airspace, required even if you dont plan to get that close. The New York SFRA The SFRA associated with the New York Class B airspace, the Hudson River and the East River is defined in FAR 93 Subpart W. It was created in the aftermath of the August 8, 2009, mid-air collision between a sightseeing helicopter operating under Part 135 and a privately operated Piper PA-32R-300. Other than some specific changes, the SFRA essentially makes regulatory certain procedures that were strongly recommended and printed on local charts at the time of the collision. However, these procedures now are mandated. Its obvious the N.Y. SFRA has been designed to segregate the two principal types of operations in that airspace. These include transient operations, defined in FAR 93 Subpart W as “aircraft transiting the Hudson River Exclusion from end to end without intending to significantly change heading, altitude, or airspeed.” Meanwhile, local operations also are defined by the FAR. They include any operation other than transient. Simple, eh? 288 Well, maybe. Its important for any transient operator to remember fixed- and rotor-wing aircraft are landing and departing from the heliports and seaplane bases within the SFRA. This includes, for example, sightseeing, electronic news gathering and law enforcement operations. Transient and local operations are further distinguished-and separated-by altitude. Local operations are expected to fly between the surface and up to but not including 1000 feet agl. Transients, meanwhile, should be between 1000 feet and 1300 feet agl. Any operations above 1300 feet in the Hudson River Exclusion are considered transient, also, but are required to obtain an ATC clearance for the overlying Class B airspace. At altitudes of 1300 feet and below, these operations are subject to FARs 93.351 and 93.352. The four main operational requirements for all aircraft in the affected airspace are: Maintain an indicated airspeed not to exceed 140 knots; Turn on anticollision and position/navigation lights, if equipped. The use of landing lights is also recommended; Self-announce your position on the appropriate radio frequency for the East River or Hudson River as depicted on the New York VFR Terminal Area Chart (TAC) and/or New York Helicopter Route Chart (specific reporting points are required when operating in the Hudson River Exclusion), and; Have a current New York TAC and/or New York Helicopter chart aboard. Those general requirements are supplemented, depending on the specific area in which the aircraft is being operated. For instance, if you wish to fly an airplane over the East River, you must receive authorization from ATC, regardless of whether you plan to fly in the SFRA or in Class B airspace. To obtain an authorization, contact the LaGuardia ATCT on 126.05 MHz. Washington, D.C. SFRA The D.C. SFRA is a much different animal, designed for purposes not at all related to separating traffic or preventing mid-air collisions. Instead, its designed to facilitate positive identification of the various aircraft operating in close proximity to Washington, D.C., for security reasons. As such, its requirements are much more detailed-and the penalties for violating them can be much more severe. Theres no way this article can come close to providing the understanding necessary for safe and legal operation within the SFRA. (Of course, were trying to highlight some of the reasons you need to study this and other airspace before even considering going close to it.) Just as with the N.Y. SFRA, its D.C. cousin is defined by regulation, found at FAR Part 93 Subpart V. Unlike the New York version, however, the D.C. SFRA also incorporates two additional airspace designations, the Washington D.C. Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) and the Flight Restriction Zone (FRZ). For an overview of these two areas, see our September 2007 issue. The first thing to understand about the D.C. SFRA is that, with two exceptions, every VFR flight conducted within it must be on a D.C. SFRA flight plan. Generally-another exception involves VFR operations within the FRZ-any flight service station can accept a D.C. SFRA flight plan. That doesnt mean filing one with any facility other than the Washington Hub FSS is a good idea, however, since the local folks are assuredly conversant with the procedures. Someone at an outlying facility might miss something. The flight-plan exceptions involve accessing a so-called “fringe” airport or doing pattern work at a towered airport within the SFRA. The second thing to understand is never, ever squawk 1200 within the D.C. SFRA. Thats a move guaranteed to earn you a visit from FAA enforcement. Or worse. To enter the D.C. SFRA, presuming youve filed an appropriate flight plan and are outside it, contact ATC, advise them you are inbound to an airport within the SFRA and obtain a discrete transponder code. Once you dial in the code and hear the magic words “transponder observed,” youre good to go. To depart the D.C. SFRA, you must do the same thing, which requires contacting ATC either by radio or telephone to obtain a squawk code. Put it into your transponder and call ATC on the appropriate frequency once airborne. In both cases-inbound or outbound-your D.C. SFRA flight plan is automatically cancelled when you land or when you depart the SFRA, as appropriate. Summary The SFRA concept isnt that hard to accept, but it can be difficult to comprehend when your chair is moving at more than 100 knots and youre not prepared for it. Thankfully, the FAA has developed appropriate training to cover the details of both areas, as described in the sidebar on the opposite page. Importantly, successful completion of the course covering the D.C. SFRA is required by FAR 91.161 if you plan to fly VFR within 60 nm of the DCA VOR/DME. Weve passed both courses; we wont say theyre fun, but they are relatively painless.