by Joseph E. (Jeb) Burnside

We know that oxygen deprivation is something to avoid while trying to fly an aircraft. Its been drilled into us through our training and, if the popularity of portable oxygen systems is any yardstick, pilots who spend any quality time at altitude on longer flights realize they may need a little help. But few pilots actually get to experience the effects of oxygen deprivation.

The FAA and its Oklahoma City-based Civil Aerospace Medical Institute (CAMI) have established the Aerospace Physiology Training program allowing civilian pilots to do just that. The training is given at the altitude chambers operated at various locations throughout the country by the U.S. Air Force, and is designed to not only educate pilots on the realities of high-altitude flight but to ensure they can recognize the various altitude-sickness symptoms when they occur and know what to do about them. In addition to serving as one phase of the FAAs Aviation Safety Program-the Wings program-the training is also acceptable toward qualification for the high-altitude operations endorsement required by FAR 61.31(g).

Since everyone reacts to hypoxia and other altitude-related problems differently, the only way for a pilot to really know and understand how he or she might be affected is to go to altitude and breathe ambient air. Of course, this is impractical, and can be dangerous unless the conditions are controlled. Thats the main value of the Aerospace Physiology Training program. So, earlier this year, I signed up to participate in the training conducted at Andrews Air Force Base in nearby Maryland.

Most of the programs morning is spent in the classroom, covering a variety of topics associated with high-altitude flight. These topics include what can happen to human body in the flight levels (nothing good), and what to do about it (get on oxygen and perform an emergency descent). See the sidebars for details on hypoxia and a discussion of some other altitude-related illnesses.

A Relaxed Atmosphere

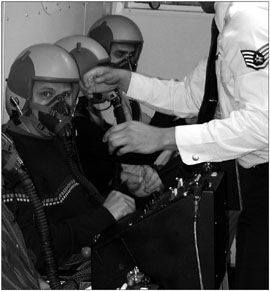

After the mornings lecture and lunch outside the facility, it was time to move into the chamber itself, don the helmets, connect the oxygen hoses and do that for which we all came here.

In the chamber, each participant sits at their assigned station, a seat against the wall, which is equipped with an oxygen-system control panel, plus connections for the masks supply hose and intercom. A military-quality portable oxygen bottle is mounted underneath each seat for emergencies and each participant gets to try it out it, briefly, to demonstrate its use.

Once the students were settled in the altitude chamber and final equipment checks were complete, all participants immediately started breathing 100 percent oxygen to purge problematic nitrogen from our bloodstreams so that the sudden decompression scheduled during the chamber ride would have a minimal impact.

Dumping The Cabin

Soon, it was time to close the chambers main door and get down to business. After pre-breathing O2 for 30 minutes, the students and instructors were ready for the first demonstration, a climb to 5000 feet, at around 1000 fpm (all climbs and descents, except for rapid decompression demonstrations, are made at roughly this rate). Once stabilized at 5000 feet, another equipment and howgozit check was performed, with all participants giving a thumbs-up response.

We were soon climbing again, up to 18,000 feet or so, for another check of the oxygen systems. This climb was designed to ensure no one would have any problems at that altitude with the coming rapid decompression. No one did, so we started down again, back to 5000 feet. This is where experience at clearing ones ears-gained either through some Scuba diving or a few too many slam dunk approaches at ATCs request-came in handy.

We had been told to expect-and some video shown earlier in the day had confirmed-that the rapid decompression demonstration would generate some fog or mist in the chamber. That didnt happen, however; what did happen was pretty anticlimactic.

We had dropped our oxygen masks and were breathing ambient, 5000-foot air when the chamber operators started raising the altitude. No mist formed, but the strategically placed altimeter started winding up enthusiastically on its way to roughly 18,000 feet. Having been there, done that, 18,000 wasnt all that big a deal for most of the students, but at an instructors urging, we all donned our masks again, ganged the control switches and went back on 100-percent O2. So much for the rapid decompression demonstration.

Getting Stupid

Now, we were ready for the big show-a chamber climb to 25,000 feet and some exercises designed to demonstrate how quickly one can succumb to oxygen deprivation.

The climb from 18,000 to 25,000 feet didnt take long and the instructors-two in the chamber and three outside, watching through large ports-used that time to distribute plastic slates and dry-erase markers. The first side of the slates had some fill-in-the-blank questions while the other featured a visual acuity exercise.

Level at FL250 and on command, we all dropped our masks and glanced at the clock to time our exposure. First writing our name on the slates, we then began working through the exercises on the first side, which included math and word problems. (Note to USAF: Some of us arent capable of doing those math problems at sea level with a supercomputer, much less at FL250 with a pencil.) And thats when it started getting interesting.

Ive flown in the teens without oxygen and know how lethargic I feel and how slowly my thought processes work. As my body became more acclimated to the thin air at 25,000 feet, lethargic and slow didnt begin to describe the complete incompetence with which I went through the exercises on the slate. Writing my name was an effort, as was focusing both on the slate and on the visual acuity exercise on the reverse. To say the speed with which I became stupid from oxygen deprivation was breathtaking would be to mix my metaphors, but there it is.

After only three minutes breathing 25,000-foot air, Id had enough. I was very uncomfortable-bewildered, clumsy, half-blind from an inability to focus and starting to breathe more rapidly than normal. Others around me seemed to be doing okay, but one or two in the chamber had already donned their masks and ganged the switches to get 100-percent oxygen.

Slowly realizing this wasnt going to get better and that Id discovered what I came for-the physical and mental sensations of real, U.S. government-approved, Grade A hypoxia in a controlled environment-I briefly fumbled with my mask, snapped it into place and ganged my switches.

After a few deep breaths, I could again focus on the chambers opposite wall, my anxiety level was starting its own descent and I was able to turn my head and see how the other students were doing. The instructor sought and received my thumbs-up and then moved on to other students. I wasnt normal yet-that would take a while longer-but I was much more comfortable, feeling much less stupid and deep in thought about what would have been the outcome if I had been single-pilot over the Rockies and this had snuck up on me.

Count On Me

Soon, all but one student had donned their masks and were breathing more or less normally. The instructors started paying close attention to our mask-less student, who said he felt fine, and asked him if he would participate in a quick exercise. He agreed, so an instructor outside the chamber asked if he would mind counting backward from 100 by six.

You know, like six, twelve, eighteen, but backward from 100. The student said hed be happy to try and the instructor asked him to begin. Our hero: One hundred, one hundred and four, one hun… at which time the entire chamber and the instructors outside burst out laughing.

Still smiling, one of the in-chamber instructors bent over the student and gently but firmly reaffixed his mask, ganging his switches. Soon, he was back to normal, and giving a thumbs-up. Later, when told of the episode, he recalled the conversation, but didnt remember the details and said he felt fine throughout. Thats the euphoria of oxygen deprivation talking.

Conclusion

The day concluded with a debriefing on the chamber ride, followed by an excellent presentation on night vision, conducted in a pitch-black room and featuring a detailed examinaton of a variety of optical illusions one can experience at night. Given the fact that I and others were still not back to normal with respect to our blood oxygenation, the presentation highlighted the Air Forces recommendations to use oxygen at night when above 5000 feet.

To put it bluntly, short of topping off your fuel tanks, this is one of the best uses of $50 one can make in general aviation. To me, anyway, learning how quickly and deeply hypoxias effects can manifest themselves-and how they can degrade so many of the senses required to safely fly an aircraft-was an eye-opening experience, one I would highly recommend to anyone who is serious about his or her flying. I would especially recommend it to anyone flying a turbocharged airplane or better, or to anyone who routinely uses the low-to-mid teens on cross-country flights.

The FAA/CAMIs Aerospace Physiology Training is offered at 17 locations throughout the U.S., including the FAAs Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center in Oklahoma City, Okla. For background and enrollment information, see the FAA/CAMI Web site, www.cami.jccbi.gov/aam-400/phys_intro.htm.

Also With This Article

“Hypoxia”

“Altitude-Related Illnesses”

“Time Of Useful Consciousness”