by Jeb Burnside

When an aircraft is damaged and subsequently rebuilt, care must be taken not only to ensure that the manufacturers instructions are followed but that everything works as it should. Sometimes, in our haste to get an airplane back in the air, we cut corners. We dont use alternate methods to verify that all the big parts are attached and working as they should. Even though an initial test flight indicates the engine runs and the airplane flies, it doesnt mean everything is working as it should. A brand-new Private pilot flying a just-repaired Cherokee 180 learned this lesson the hard way.

On August 3, 2002, at about 1539 Eastern time, a Piper PA-28-180, crashed into trees and terrain just off the approach end of Runway 7 at the Cheraw Municipal/Lynch Bellinger Field Airport in Cheraw, S.C. It was a typical summer afternoon in South Carolina, with clear skies, warm temperatures and good visibility; just the kind of afternoon on which a new Private pilot would want to head out to the airport and fly his new-to-him Cherokee around the patch.

And this pilot met both tests. He had earned his Private certificate a scant three months earlier. Since beginning his flying career, he had accumulated some 61.5 hours of total time, with 19.3 hours of pilot-in-command time in the same make and model as the accident aircraft. Additionally, the Cherokee was a relatively new acquisition; he had purchased the Piper only 10 days after his successful Private pilot checkride; it had passed an annual inspection within the previous three weeks. The airplane had been operated for 1.82 hours since the annual inspection was completed.

On the day of the accident, the pilot/owner was observed performing a preflight inspection and then taxiing to Runway 7. The Cherokee then took off and remained in the traffic pattern. One witness noted the airplane appeared to be at traffic-pattern altitude on the downwind leg. Another witness reported observing the airplane on the downwind leg and losing power at about of the length down the runway toward the threshold. That same witness added that the accident aircrafts engine sounded as if it …wanted to start once more but then did not refire. A third witness reported hearing the engine and stated, It was [sputtering] then it cut back on; then it went back off. Several witnesses reported that, from the point the engine lost power, the flight path was similar to an airplane flying a normal traffic pattern. Subsequently, the airplane was observed flying low on its final approach. It then disappeared behind trees. The pilot/owner died in the crash; the only passenger aboard survived with serious injuries.

Investigation

The airplane came to rest upright on a heading of 246 degrees, approximately 46 feet from the initial ground scar location. A straight-line heading of 070 degrees was noted from a tree impact point to the main wreckage. All components necessary to sustain flight were attached or partially attached to the airplane.

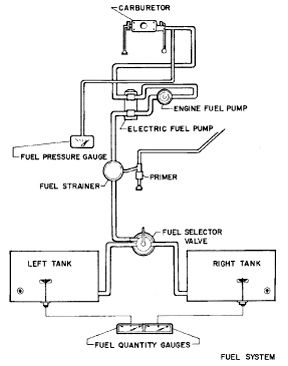

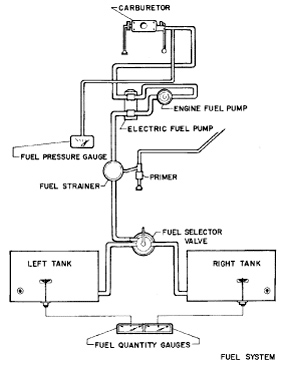

The left wing fuel tank was intact; it contained approximately 13 gallons of 100LL. The right wing fuel tank held approximately 20 ounces of 100LL. The tank was not compromised and there was no evidence of fuel stains aft of the fuel filler cap or of the sump drain. No obstructions of the fuel delivery or fuel vent system were noted. The fuel selector was found positioned near the right fuel tank detent; impact damage was noted. No fuel was noted at the lines at the fuel selector valve; the electric fuel pump switch was found in the off position. Only residual fuel remained in the fuel hoses located in the engine compartment area; the fuel hoses had not failed. Approximately one ounce of fuel was drained from the carburetor bowl. The engine was removed from the airplane and a serviceable propeller was installed. The engine was started and operated to approximately 2250 rpm using only the engine-driven fuel pump; investigators found no discrepancies during the engine run.

Provenance

This was not the first time this aircraft had been damaged. According to the NTSB, the airplane was involved in a bounced-landing event on November 23, 2000, which resulted in minor damage that did not require filing an accident or incident report with the safety board. Nevertheless, the insurance company considered the airplane a constructive total loss and sold it to an aircraft salvage company on March 15, 2001. Subsequently, the the airplane was disassembled and sold to a subsidiary of the salvage company before being transported to South Carolina and purchased by the accident pilot.

According to the mechanic who reassembled and repaired the airplane-and performed the last annual inspection-the aluminum fuel lines aft of the fuel selector valve were bent and damaged to the point that he could not determine routing of the lines to the fuel tanks. After the damaged lines were repaired and the wings were installed, he connected the fuel line from the right fuel tank to the forward port of the fuel selector valve and the line from the left fuel tank to the aft port of the fuel selector valve.

Following repairs to the airplane, the mechanic added 10 gallons of fuel to each tank to run the engine and check for leaks; the fuel tanks were filled before completing the annual inspection. Following the annual inspection, he test flew the airplane to check the flight control rigging and to look for any other problems; no discrepancies were reported.

The NTSB determined that the fuel line from the forward side of the fuel selector valve should be connected to the left fuel tank and that the line from the aft side of the fuel selector valve should be connected to the right fuel tank. In other words, the connections to the fuel selector were reversed when the airplane was reassembled.

Probable Cause

The NTSB found the probable cause of this accident to be the misrouting of the fuel lines to the fuel selector, which resulted in the use of a fuel tank with inadequate fuel supply, fuel starvation, and the loss of engine power. Contributing was the pilots inadequate remedial action for conducting an emergency landing.

Despite several flights by three different pilots before the accident, no one thought to confirm that the wing tanks fuel levels accurately reflected the selector position and expected fuel burn. How much longer the incorrect installation would have gone unnoticed is anyones guess-perhaps when the airplane was flown out of the pattern on a cross-country flight and the fuel gauges were noticed; perhaps when the wrong wing got heavy.

Of course, even though the fuel lines were installed incorrectly, topping off the fuel tanks before this flight apparently would have prevented the accident.

Still, the pilot failed to react to the emergency. Not only did he not switch tanks and turn on the boost pump, he flew a normal pattern instead of immediately turning toward the runway. This was despite most of his flight time being in the same type of aircraft. Whether he had not been adequately trained in engine-out procedures or simply froze at the controls well never know.

Also With This Article

“Aircraft Profile: Piper PA-28-180”