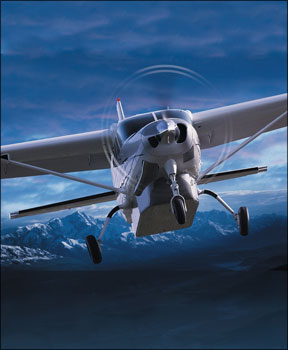

Theres virtually no substitute for Cessnas Model 208 Caravan as an economical, high-volume utility airplane. Thats why it was a shock to the industry when the FAA considered revoking the Caravans “known ice” certification. After becoming indispensable as a small-package workhorse and charter/backcountry passenger 288 transport, a terrible trend began to develop: Caravans were crashing after encountering icing conditions. The FAA threatened to pull the 208s certification for flight in icing unless industry figured out how to reverse the trend. Somebody had to save the Caravan. What operators, Cessna and the FAA did may change the way we all think about icing certification. “Troubled Our Industry” The Regional Air Cargo Carriers Association (

Facing potential operational restrictions on the Caravan that would eliminate operators ability to dispatch in icing conditions, RACCA in early 2006 quickly convened its Safety Committee to study the mishap record and develop a course of action. Committee chairman Richard Mills knew they needed to fast-track a solution before another icing season set in. To do so they had to enlist some heavy-duty help from Cessna and the FAA. “We were very concerned about the accident rate as well as the [financial] loss rate” of downed aircraft and cargo, Mills says. “We were afraid FAA, based on urging from the National Transportation Safety Board, was being forced into taking Draconian action against the aircraft.” In addition to pilot fatalities, RACCA members simply could not afford to continue to absorb the financial loss of accidents; but neither could they operate if the Caravan was taken out of winter service.

The Committee called a meeting between CEOs of Caravan-operating firms from across the U.S. and a host of Cessna engineers. Bernstein commends Cessna CEO Jack Pelton for his personal participation in the meeting on very short notice, crediting Pelton for much of the resulting plans success.

The Plan

The RACCA Safety Committee/industry/Cessna plan evolved to follow two complimentary lines:

First, Cessna would study aircraft hardware and pilot training as they relate to airframe ice. Meanwhile, RACCA would work to get the FAA on board with a serious effort to mitigate icing risk and preserve the Caravans “known ice” certification.

Mills insisted the “FAA absolutely had to be involved” from the beginning. He convinced the FAAs Associate Administrator for Aviation Safety Nick Sabatini and Director of Flight Standards James Ballough to take an unusually active role in ensuring the icing safety of the Caravan fleet. “Typically the FAA directs industry to solve problems, then reviews and approves the result,” Bernstein reports. In this case, RACCA was able to convince Sabatini and Ballough the potential operational

Shawn Roberts

288

impact was so great they had no time to solve the problem and then pursue FAA approval of a revised icing certification. The FAAs management agreed, and took an active role in the process while it was underway. It called in Paul Pellicano, a scientist and FAAs leading expert on airframe ice, to work directly with Cessna and RACCA.

The Result

Several changes resulted from the RACCA/Cessna/FAA collaboration. First, the FAA issued a series of Airworthiness Directives (ADs) requiring changes in the way Caravans were equipped and operated if known-icing certification was to be retained:

First, hardware and AFM changes were made to ensure better preflight inspection of upper airframe surfaces for ice or snow contamination. This includes a requirement to physically check a representative portion of the upper wing and tail to ensure they are ice-free within five minutes of taking off. The so-called “tactile inspection,” says Mills, opened a “whole set of problems” for compliance, because “even in the best of conditions its a challenge to inspect and then take off in under five minutes.”

Then, additional deice boots on previously unprotected areas like wing struts and the leading edge of the cargo pod were required.

Finally, the most recent AD (with the somewhat demonic number 2006-06-06) requires operators to insert a new ice-oriented supplement in the Approved Flight Manual (AFM), placing hardware and even pilot training requirements on Caravan operators.

This AFM supplement is the true success story of the RACCA/Cessna/FAA collaboration.

One of the supplements most notable elements is a Low Airspeed Awareness System (LAWS) to warn the pilot of unsafe airspeeds in ice. Activated when the propeller heat switch is turned on, the LAWS sounds a buzzer and flashes a panel annunciator whenever the indicated airspeed gets below 110 knots, warning the pilot to check for and deal with airframe ice.

Another supplement feature is updated climb performance charts for planning takeoffs in icing conditions, with anticipated climb rates and gradients for an ice-laden airframe. Of course, what goes up, must come down, so the AFM supplement also includes drift-down charts for planning controlled ice-contaminated descents.

These tables, created by FlightSafety International instructor Brad Silverstein working with Cessnas flight test engineers, provide a “new level of ice awareness,” says Mills. They provide a tool to preplan a route when deciding whether to dispatch (“what are my chances of completing this flight?”), and if the pilot finds ice en route, an “easy way to determine if you should be up there or not.”

Other changes made as a direct result of these collaborative efforts include an upgrade of Cessnas existing Caravan Cold Weather Course (see the sidebar, “Cessna E-learning,” page 20) and a new operating limitation requiring the pilot-in-command to have successfully completed the CCWC (in-person or online) within the preceding 12 months to be legal to launch into actual or suspected icing conditions. For the first time, “known ice” certification was tied to pilot training as well as aircraft hardware.

Expanding the Plan

Nine of the 30 Caravan ice-related mishaps resulted from failure to de-ice the airplane before takeoff. Stan Bernstein relates: “Currently there is no ground deicing standard for approval under FAR 135,” under which most Caravans fly. As a result, RACCA hopes to expand the Caravan ice plan to include FAA-approved ground deicing operations along Part 121 lines that permit, when using Type 3 or 4 deicing fluid, much longer ground hold times to mitigate the operational hassles of the current five-minute inspection-to-takeoff rule.

Saving the Caravan

Bernstein credits the success of this plan to Jack Peltons “very cooperative spirit” and FAA Director of Flight Standards Jim Ballough as “the catalyst” that made this happen. Overall, Bernstein calls this a “remarkable story of industry, the OEM and FAA getting together to produce very satisfactory results”-a level of cooperation, he quips, that “may never have happened before.”

“We had no icing incidents last year,” Bernstein cautiously notes about the 2006/2007 North American winter. But “were not letting our guard down.” In fact, there was one ice-related incident in 2006 in Norway, and three events in 2007 that at least on preliminary investigation may be ice-related. There is no such thing as an all-weather airplane, and this is no more evident than when you consider airframe ice.

But in a truly unique example of cooperation, key visionaries at RACCA, Cessna Aircraft and the FAA turned away from the easy path of revoking or severely limiting the icing certification of the C208 Caravan. Instead, they crafted a workable solution that includes hardware upgrades and targeted pilot education, saving the Caravan for its niche in cargo and utility transportation.

The lessons learned-including focused, recurrent training, improved flight planning with flight-tested data and specialized preflight procedures, to name three-all can be applied by those of us flying other aircraft in potential icing conditions.

Tom Turner is a CFII-MEI and Master CFI who frequently writes and lectures on aviation safety.

Perhaps it’s time to move on from the Cessna 208. Going through gyrations of training and regulating and tweaking can’t fix a fundamental flaw that this aircraft cannot handle icing conditions.

How many more people have to die before it’s restricted to climates without icing?