By now, U.S.-based flight instructors and training organizations should be fully up to speed on last year’s formal implementation of the airman certification standards (ACS), which is designed to eventually replace all practical test standards (PTS). For now, only the private pilot and airplane instrument rating checkrides employ the ACS, but more are coming. The new standards went into effect June 15, 2016—if you’re in the primary training environment and don’t know about the ACS, you haven’t been paying attention.

The ACS presents a better-organized set of requirements for the desired certificate or rating while basically requiring the same maneuvers as the old PTS. Risk management concepts are woven into the new standards and require applicants to apply them during the checkride. And there are other changes. For example, the ACS slow-flight standards have been revised and have raised concerns among independent flight instructors, training organizations and safety advocates. To understand why this is a thing, you also need to understand how it’s been done for decades.

D. Miller/Creative Commons

The Slow Flight Change

Prior to development of the ACS, “slow flight” basically meant flying the airplane at its minimum speed. The goal is to establish that minimum speed, one “at which any further increase in angle of attack, increase in load factor, or reduction in power, would result in an immediate stall.” Typically, this means flying with the stall warning (whether a horn, buzzer or light) fully and steadily on. Legions of pilots have spent hours and hours of quality time hanging their airplane on its prop with the stall warning blaring, learning to balance on the head of a pin.

The object is and was to maintain altitude, within 100 feet, heading within 10 degrees, and angle of bank also within 10 degrees. Airspeed could vary upward by 10 knots, but—as the definition implies—you couldn’t fly much slower or you’d stall. Stalling out of the maneuver usually meant you got to recover and do it again until you got it right, at least in training. On the checkride, you might get two chances before earning a pink slip.

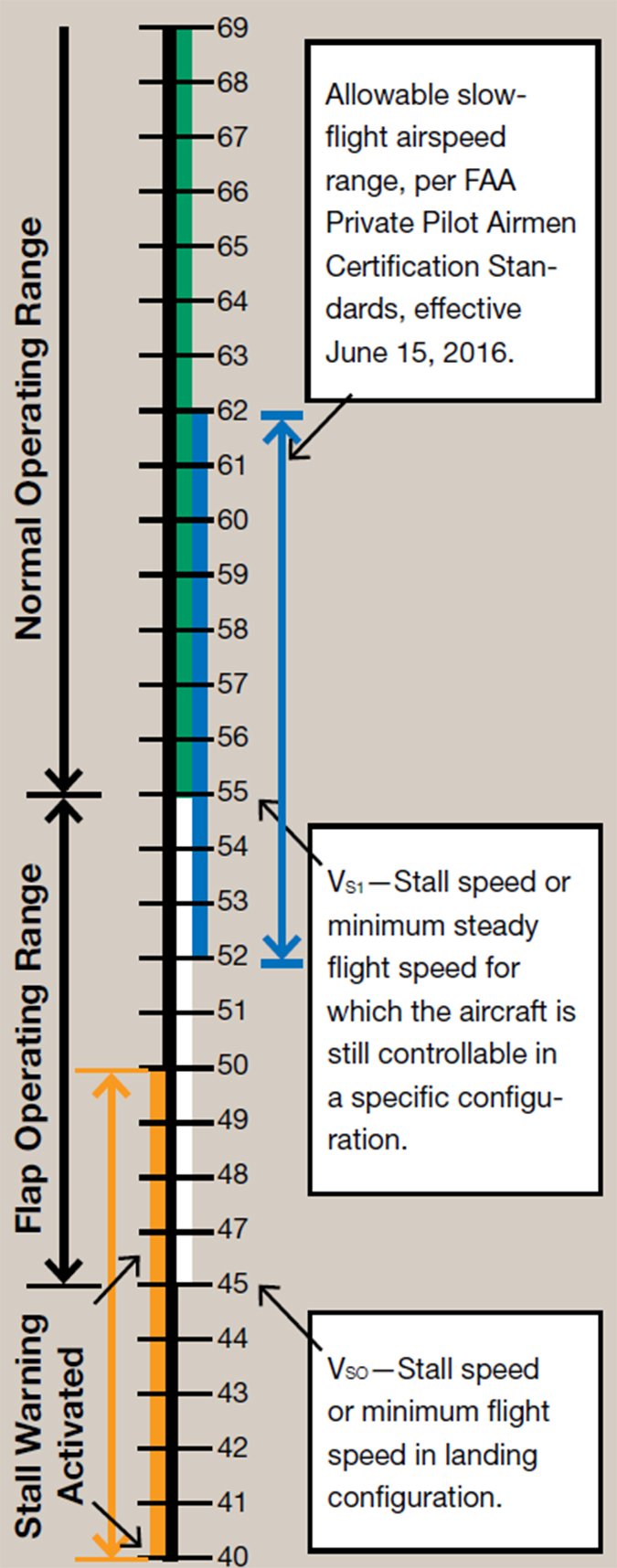

But those were the good old days. The new ACS changes the definition of slow flight to “an airspeed, approximately 5-10 knots above the 1G stall speed, at which the airplane is capable of maintaining controlled flight without activating a stall warning.” Because the ACS language requires slow flight at no more than the 1G stall speed in the chosen configuration, pilots and instructors need to rethink their objectives and what constitutes satisfactory performance. No longer will students and applicants be hovering around the bottom of the white arc or the bottom of the green one, depending on airplane configuration. Instead, they’ll be doing it at around five knots higher speeds.

At this point, it’s important to note that, elsewhere in the ACS, and in the PTS, power-off and -on stalls are presented and must be demonstrated. Both documents require recognizing and recovering “promptly after a full stall has occurred.” As a result, the private pilot applicant still must demonstrate full stalls and their recovery, just as before the ACS. Now, however, in addition to a stall series, the applicant also must learn two different ways to perform slow flight. One way is to set up for stall demonstrations and to, you know, actually land and take off. The other way is to get through the slow-flight demonstration on the checkride itself.

Reasons For the Change

The new ACS was released early last year, for implementation June 15, 2016. By August 30, 2016, the FAA issued SAFO 16010, a Safety Alert for Operators, Maneuvering During Slow Flight in an Airplane, as a way of clarifying the changes and the reasons behind them. The SAFO doesn’t mince words: “Loss of control in flight is the leading cause of fatal general aviation accidents in the U.S. and commercial aviation worldwide…. To address loss of control in flight in general aviation, the [FAA] revised the evaluation standard for the slow flight maneuver and is aligning the associated guidance accordingly.”

In other words, the new slow-flight requirements in the ACS and now explained in greater detail by the SAFO—at least until a new, revised Airplane Flying Handbook comes out—are specifically designed to help prevent loss-of-control in-flight accidents, or LOC-I. The LOC-I accident type has seen significant focus in recent years, at all training levels. In fact, there’s speculation the ACS, the SAFO and the forthcoming revisions to the AFH are being revised to minimize “real” slow flight, as some might call it, in favor of adopting training standards geared more closely to the skills and operational characteristics expected of crews flying jet transports. The reasons for this are clearly stated, but still raise concerns.

As the SAFO hints, the changes in defining and demonstrating slow flight are geared as much toward trying to prevent LOC-I accidents in personal airplanes as they are toward addressing shortcomings identified in the wake of highly visible transport crashes, examples of which include Colgan Airways Flight 3407 and Air France Flight 447.

But there’s a problem with all this: Flight instructors and training organizations now will be forced to train students to perform slow flight in two different ways. One of them involves the kind of slow flight we perform in normal operations, like taking off and landing, as well as in performing actual stall demonstrations during primary training, checkrides and for maintaining currency. The other will be to get through the practical test.

Why Do Slow Flight, Anyway?

Why is slow flight such a big deal? Well, it normally isn’t. That’s because flying slowly—as when landing or taking off—is part of an airplane’s normal operating range. As this article’s main text notes, SAFO 16010, Maneuvering During Slow Flight in an Airplane, was issued to clarify the new ACS. It states, “Airplanes operate at low airspeeds and at high angles of attack during the takeoff/departure and approach/landing phases of flight. It is essential that pilots learn: (1) the airplane cues in that flight condition, (2) how to smoothly manage coordinated flight control inputs, and (3) the progressive signals that a stall may be imminent when deviating further from this condition.” Existing guidance in the Airplane Flying Handbook (AFH, FAA-H-8083-3B) puts it more succinctly, “The objective of maneuvering in slow flight is to understand the flight characteristics and how the airplane’s flight controls feel near its aerodynamic buffet or stall-warning.”

The AFH notes that understanding, practicing and performing slow-flight demonstrations “also helps to develop the pilot’s recognition of how the airplane feels, sounds, and looks when a stall is impending. These characteristics include, degraded response to control inputs and difficulty maintaining altitude. Practicing slow flight will help pilots recognize an imminent stall not only from the feel of the controls, but also from visual cues, aural indications, and instrument indications.”

Presently, the AFH states slow flight’s two main elements, at least as far as training and testing go. They are:

1. Slowing to, maneuvering at, and recovering from an airspeed at which the airplane is still capable of maintaining controlled flight without activating the stall warning—5 to 10 knots above the 1G stall speed is a good target; and

2. Performing slow flight in configurations appropriate to takeoffs, climbs, descents, approaches to landing, and go-arounds.

How We’re Supposed To Do Slow Flight Now

The revised evaluation standard requires the pilot to maintain a speed referenced to the 1G stall speed. According to the FAA’s SAFO, Maneuvering During Slow Flight in an Airplane, “One way to set up for the maneuver is to slow the airplane to the stall warning in the desired configuration and note the airspeed.” The SAFO recommends:

• Next, pitch down slightly to eliminate the stall warning, adjust power to maintain altitude, and note the airspeed required to perform the slow flight maneuver in accordance with the standard. For example, the pilot may first note that the stall warning comes on at 50 knots.

• A slight pitch down to eliminate the warning, while adjusting the power to maintain altitude, might then cause the airspeed to increase to 52 knots. That 52 knots would be the base airspeed to perform the slow flight maneuver.

• The pilot can adjust pitch and power as necessary during the maneuver to stay within the ACS airspeed standard of +10/-0 knots (i.e., using the example, the range would be 52-62 knots) without activating the stall warning.

• By setting up the maneuver this way, the pilot can achieve similar angles of attack for the maneuver, regardless of weight or density altitude, and meet the objectives of the slow flight task.

Pavlovian Response

Given the focus on LOC-I, it shouldn’t be a surprise the FAA’s and industry’s efforts to minimize this type of accident are permeating many policy changes. These changes include certification standards (e.g., supplementary angle-of-attack indicators are easier to install in certificated airplanes, thanks to rule changes) and now include training standards. But is it a good idea to redefine—some would say downward—standards for slow flight and for recognizing stalls?

The answer comes from the SAFO: “The FAA does not advocate disregarding a stall warning while maneuvering an airplane.” In other words, the FAA is concerned that slow-flight demonstrations, as they have been performed since, well, the beginning of time, actually are training pilots to minimize or ignore the actual stall warning necessary to perform them under now-obsolete training standards. The SAFO continues: “With the exception of performing a thoroughly briefed full stall maneuver, a pilot should always perform the stall recovery procedure when a stall warning is activated.”

The FAA’s reasoning for changing its policy on slow flight also is discussed in the SAFO. It says, “According to 23.207(a), part 23 certificated airplanes must have a ‘distinctive stall warning.’ That distinctive warning alerts a pilot of an impending stall and therefore prompts a pilot to perform a stall recovery. When the manufacturer conducts airplane certification testing, the stall warning is required to ‘begin at a speed exceeding the stalling speed by a margin of not less than 5 knots and must continue until the stall occurs.’

“Based on the airplane certification standard for a stall warning, a pilot following the AFH guidance of 3-5 knots above the stall speed would most likely be intentionally flying with the stall warning activated, which is a stall indication. Therefore, the AFH guidance to maneuver ‘without indication of a stall,’ is inconsistent with the suggested airspeed range of 3-5 knots above the stalling speed provided in that same handbook. The PTS requirement to fly at an airspeed at which any further increase in angle of attack would result in a stall means the applicant would have to perform the maneuver with the stall warning activated, which is also inconsistent with the AFH. Advocating maneuvering the airplane just below the critical angle of attack with the stall warning activated is neither desirable nor intended.”

Putting It All Together

So…what does all this mean? For now, the answer depends on your role: Are you a flight instructor teaching primary students, or doing flight reviews? Are you a certificated pilot wondering how to get through a flight review, or to which standard(s) you should train going forward? Are you a student pilot wondering what all the drama is about? The sidebar above may help answer some of those questions. Some situations and answers are simple; some are not.

Even more confusing: What about applicants for certificates like commercial pilot, or a multi-engine rating? As of this writing, the commercial pilot PTS contains the “old” verbiage: The applicant is expected to establish and maintain “an airspeed at which any further increase in angle of attack, increase in load factor, or reduction in power, would result in an immediate stall.” That’s not what’s now expected of private pilot applicants.

How is it that having two different slow-flight standards is a good thing?