Having owned an aircraft maintenance facility, I’ve seen a lot of expensive damage to airframes and engines over the years directly resulting from improper winter care by the owner. Winter flying can be very rewarding and enjoyable for you and your passengers with the proper planning. But if winter flying isn’t your cup of hot tea, and your airplane will sit outside, you may wish to consider what you can do to make that harsh environment a bit easier on it.

Regardless of whether the airplane will be active during the winter months or secured until spring, we can prepare for the season by identifying some of the pitfalls pilots and owners may encounter. For example, owners may wish to perform the manufacturer’s recommended engine and airframe storage procedures if the airplane will be in non-flying status. Others may wish to take steps designed to ensure safe, reliable operations, many of which may fall well within the FAA’s preventive maintenance rules owners can perform. Regardless, now’s a good time to think about how we’ll handle winter.

Winter Maintenance

For example, and regardless of how many flight hours have passed since the last oil change, putting in fresh oil and a new filter can help minimize corrosion-causing moisture inside the engine. Before performing the change, warm the engine by flying for 30 minutes or so, then drain the old stuff. Replenish it with winter-grade or multi-viscosity oil.

Along with the oil, the airplane’s electrical and ignition systems may need attention to ensure easy starting and expected performance. Spark plugs should be cleaned and gapped/replaced prior to winter’s onset, and any postponed magneto maintenance accomplished. The aircraft battery should be checked for its rated capacity by testing, not guessing. Battery manufacturers Concorde and Gill both have specific information on capacity checks to determine if your battery is in good condition.

Cold-weather starting, even with preheat, can be difficult under the best conditions and a weak magneto (or battery) can make the difference between a successful start and hours on the ground waiting for another try. Jump starting and hand propping an aircraft equipped with a starter is asking for trouble, especially during cold weather. Meanwhile, quick-charging a dead battery can cause it to fail internally.

Consider removing the battery and storing it overnight in a heated area before the next day’s flying. A battery in poor condition is not only a safety issue but can lead to overpriming and an engine fire while starting. (The most expedient way to extinguish an engine fire during starting is to continue cranking the engine—it helps to have a fully charged battery—and suck the fire back into the engine, where it belongs.)

Additional preventive maintenance items can include draining all sumps and checking for water before freezing weather comes and the liquid water in the fuel system becomes ice. Ice in fuel systems can block fuel screens, valves and filters, resulting in engine failure. Never use an automotive deicing or anti-icing product anywhere near an aircraft but especially not in its fuel. All of it is bad news and can require quite expensive repairs. If you absolutely must use some kind of deicing fluid, consider products offered by companies that can supply the proper supplies and equipment for general aviation aircraft, like Aircraft Deicing Inc., at www.aircraftdeicinginc.com. The company offers fluid and equipment approved for aircraft use.

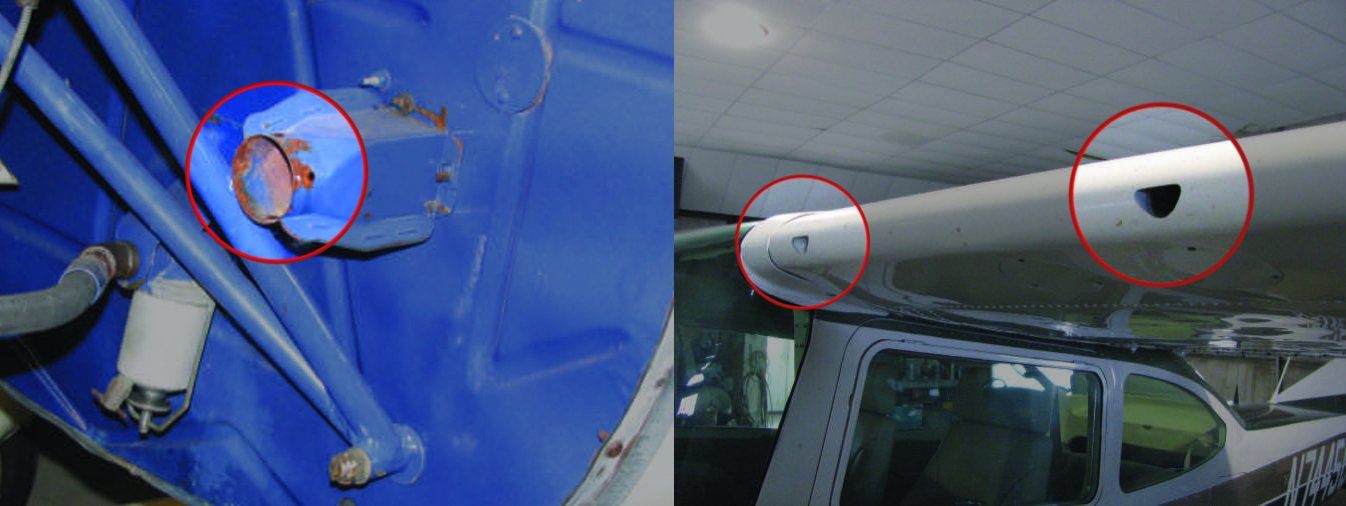

Lubricate the aircraft with the proper grease or lubricant prior to winter to purge all traces of water out of bearings and bushings. Hydraulic and aircraft braking systems need to be bled and the old fluid (possibly contaminated with water) purged from the system with fresh prior to winter temperatures. Control cable tensions should be checked and adjusted for cold weather as they can change with the temperature. Engine control cables that are stiff and sluggish during warm weather aren’t going to get better in the winter and may become impossible to operate. It may be wise to replace or purge and re-lubricate them before you have a problem.

Preparing for Winter Parking

If you plan to conduct regular operations during winter, you should give some consideration to how and where your airplane will be stored. Even when it’s in a hangar, snow-removal operations and poorly designed doors can interfere with your regular access and complicate your flying. Consider these tips when readying for winter:

– When on a tiedown, select a location offering a clear path to your aircraft, an electrical connection for preheat and proper tiedown chains or ropes.

– Where will the snow removal equipment deposit the snow? Where are the auto routes and taxiways that will be kept open during the winter? Where will the prevailing wind come from during a winter storm? Do you want your plane facing into the wind?

– Is there a low area or storm drain near where your plane is parked that will allow standing water to turn to ice, possibly trapping your plane for the entire winter season?

– If you hangar your airplane, sliding hangar doors can freeze in their tracks, and high winds also may prevent you from opening them.

– Since snow-removal equipment can’t get too close to your hangar, it’s likely you could be forced to shovel plowed snow and ice.

– Exercise extreme care when pushing or towing your airplane on frozen pavement, which may actually be a sheet of ice.

Long-Term Preservation?

Winter weather is very hard on aircraft, especially those tied down outside. If you do not intend on flying your aircraft during the winter, consider preserving it rather than just leaving it as it was the last time you flew it. Most manufacturers’ maintenance manuals have sufficient information so an owner or mechanic can properly preserve an aircraft. Generally, an aircraft should be preserved if it is going to be inactive for more than 30 days.

While preservation generally means the aircraft won’t be flown until it is removed from storage status, that does not mean it should be abandoned until spring. Remove heavy accumulations of snow and ice, and check that the flight controls are secure, the tiedowns are intact, and that sensitive aircraft systems are protected from winter weather.

Weather considerations

Beyond maintenance concerns, winter flying poses some operational considerations. First and foremost, never attempt to take off with ice or snow on an aircraft. Ice and snow on an aircraft inhibit lift and create drag, and there is no way to determine just how much is too much. The only way to ensure a safe takeoff is to remove all snow and ice.

The best method of snow and ice removal on the ground is prevention: Move the airplane into a heated hangar overnight to ensure surfaces and internal components are ice-free. The airlines have a system and set of rules to ensure safe operation, although a similar system can be quite costly for a general aviation operator.

If a hangar isn’t available, our earlier admonition against using automotive anti- or deicing fluids stands. They can damage plastic parts, windows and paint, making a mess of your aircraft. Never beat or scrape ice off your aircraft with screwdrivers or paint scrapers, or drum on the aluminum skin to remove ice. Wash and wax your plane prior to winter and invest in a set of wing, engine and tail covers or park in a hangar—whatever it costs it will be money well-spent.

Engine Preheat

Why is it advantageous to preheat an air-cooled aircraft engine but not a liquid-cooled automotive engine? One answer is the aircraft engine likely is more expensive. Another is that preheating an automotive engine in cold weather can be a good idea. The bottom line is the materials in any engine—principally steel and aluminum alloys—expand and contract at different rates. An air-cooled engine’s tolerances are designed to recognize how unevenly these various parts will expand and be cooled on initial startup while liquid-cooled engines enjoy a more uniform warm-up, thanks to their cooling method.

In both, oil must flow to all parts to ensure proper lubrication. In cold conditions, an air-cooled engine may not receive the proper flow of oil, causing extreme wear in a short time. Even if the engine starts and run, the thick, cold oil may not full circulate throughout it. Especially in cold weather, pilots always should monitor engine oil temperatures after starting to ensure it’s warm enough to flow and help prevent engine failure under the high-power conditions of a takeoff. We want to see oil temperatures of at least 120 degrees F before applying full power.

When planning for engine preheating during cold weather, it’s important to consider what you are trying to accomplish and what safety precautions are necessary. This can include having a fire extinguisher ready and keeping materials a safe distance from the aircraft. Extreme heat quickly applied may warm some engine components but also may melt or damage others, including fiberglass or composite cowlings, magnetos, starters, alternators and ignition wiring.

Teledyne Continental Motors Service Information Letter SIL 03-01, Cold Weather Operation – Engine Preheating, is an excellent reference, as is Lycoming’s Service Instruction No. 1505, Cold Weather Starting. Both recommend preheating at 20 degrees F, and we usually use 40 degrees F as the point at which it’s required. Make certain that all parts of the engine are heated, not just the cylinders, and that the oil is of the proper grade for the season. The sidebar on the opposite page has some preheating details and tips.

Some additional reference materials can include FAA Advisory Circular AC 91-13C, Cold Weather Operations of Aircraft, although this AC recently was canceled. According to the FAA, its information has been incorporated into multiple ACs, including AC 120-42, AC 135-42, AC 91-74, and AC 00-45. Another relevant document from the FAA is Special Airworthiness Information Bulletin SAIB CE-10-40R1, which addresses the hazards associated with water contamination of fuel tank systems incorporated into Cessna 100-, 200- and 300-series airplanes.

Engine Preheating—Slow And Steady Wins The Race

You may find a lot of information on the internet about preheating aircraft engines, and some of it may even be good. Over the years, some methods have proven to work well without costing a fortune while others do little to heat the entire engine but also can cause damage or even a fire. We believe there are two keys to preheating: ensuring the heat is applied slowly and evenly, and that the engine oil also is warmed before starting.

One thing to keep in mind is that air-cooled engines are designed to dissipate heat, not retain it, so heating only the cylinders won’t be very efficient and, in any case, rarely warms engine oil. Something simple like a 100-watt light bulb strategically placed and used with insulating blankets can help preserve engine heat after a flight but may not be effective in subzero temperatures on a windy ramp. Even in a cold hangar, it’s worthwhile to wrap the cowling with an insulating blanket.

A popular solution can be using a propane heater with an electric blower. The components aren’t expensive and work well in environments where the temperatures are not extreme, but even this solution requires electricity.

Electrically powered aircraft engine preheat systems are readily available and work well. Products from Tanis and Reiff, for example, are installed on the engine and require only electricity and time to raise an engine’s temperatures to levels preventing excess wear on starting. They’re difficult to leave at home and are worthy of serious consideration if you fly frequently during the winter.

Final Thoughts

Not only should your aircraft be prepared for winter, so should its pilot. This means appropriate clothing and cold-weather survival gear. Ensure your heating and ventilation systems are in good condition and equip your aircraft with a carbon monoxide detector intended for aircraft use. If you detect carbon monoxide in your aircraft, do not continue to operate it in this condition. Land at the nearest suitable airport and have the aircraft repaired. Carbon monoxide is a silent killer; don’t take a chance with your and your passengers’ lives by ignoring the warning signs. Do not block cold air vents during winter, as these may be the only way of getting fresh air to the cabin should carbon monoxide be detected.

Winter flying is safe and rewarding if you are properly prepared. Do some reading about winter flying and study your aircraft manuals. Winter weather can change quite quickly, so be prepared and always have a backup plan.

Mike Berry is a 17,000-hour airline transport pilot, is type rated in the B727 and B757, and holds an A&P ticket with inspection authorization.