There are major reasons we need to obtain a pre-flight briefing for all our flights. Airports and airspace are dynamic, and temporary flight restrictions literally can pop up anywhere. Construction, changing operations, available services, closures and, yes, obstructions all compete to materially change conditions from flight to flight, even on the same day. And then there’s the weather. The good news is the recent revolution in electronic flight bags (EFBs) means all of the data we need is either in the palm of our hand or within easy reach, even in the cockpit.

All we need to do is comprehend and interpret it. And that’s where a lot of us can fall down. Whether we realize it or not, we often need to talk to someone to get a big-picture idea of what to expect, someone able to dispassionately give it to us straight. That can be a flight instructor, mentor or simply someone hanging around the pilot’s lounge. When they’re not available, there should be a phone number we can call to talk to someone who has that big picture. Oh wait….

Anachronistic?

There is, of course, a phone number—800-WXBRIEF—we can call in the U.S. to reach the FAA’s Flight Service system. There’s also a web site. But when I call an organization whose staff has superior weather training and knowledge, there is nothing more irritating than getting a briefer who simply reads the Notams and TAFs to me. I want to stop them and say, “I just read all of that on my iPad. Tell me something I don’t already know. Give me some insights. Throw me a freaking bone.”

With this slightly jaundiced attitude toward Flight Service, I found myself planning a 1200-nm one-way trip from Idaho Falls, Idaho, to Dallas, Texas, for some flight training. So I set up the trip as an experiment to compare the value and insights I gained from my self-briefings to phone briefings from Flight Service. My hypothesis was that phone briefings are anachronistic when compared to modern, gadget-based flying information technology and tools routinely used for flight planning. I’m a bit of an AvGeek, but I know I am not alone in using technology to self-brief and being less apt to pick up a phone and dial FSS.

To quote Bob Dylan, “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.” On a CAVU summer day, with 12 gallons in the tank of a J-3 Cub, it seems a bit of a buzzkill to call FSS for a briefing just to fly to a local pancake breakfast at a private strip 20 minutes away. When I return to home plate, it is not that edifying to know that the PAPIs on Runway 17-35 remain out of service because, yes, I already read the TAF, heard the ATIS and read the Notams on the outbound.

Likewise, on my way to one of my favorite backcountry airstrips with no services, my route of flight typically passes three airports, only one of which reports weather. A call to FSS for a briefing offers very little added value and I don’t fly into the backcountry when the weather is anything but perfect. I can check TFRs on my own and see them visually on my iPad.

Finally, for eight years, I have flown a regular three-to-four hour business trip from my home airport in Idaho Falls, Idaho, to the Tri-Cities in eastern Washington. I’ve flown it more than 100 times in all seasons, in nearly all weather, and with numerous routing permutations to deal with the conditions du jour. Based on all my recent flying, it feels like Flight Service should call me to ask what conditions along the route will be.

Testing The Hypothesis

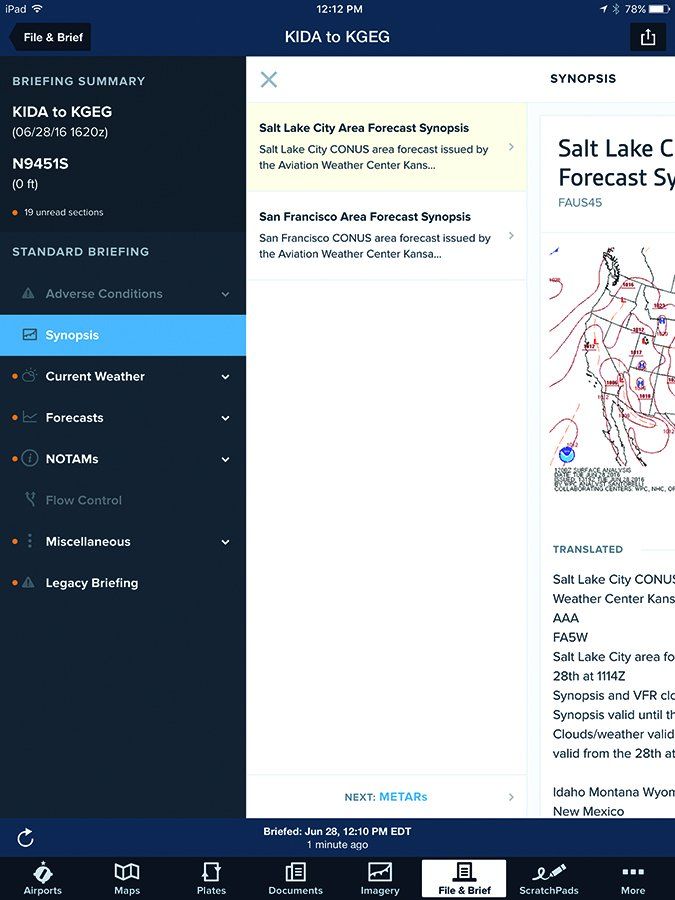

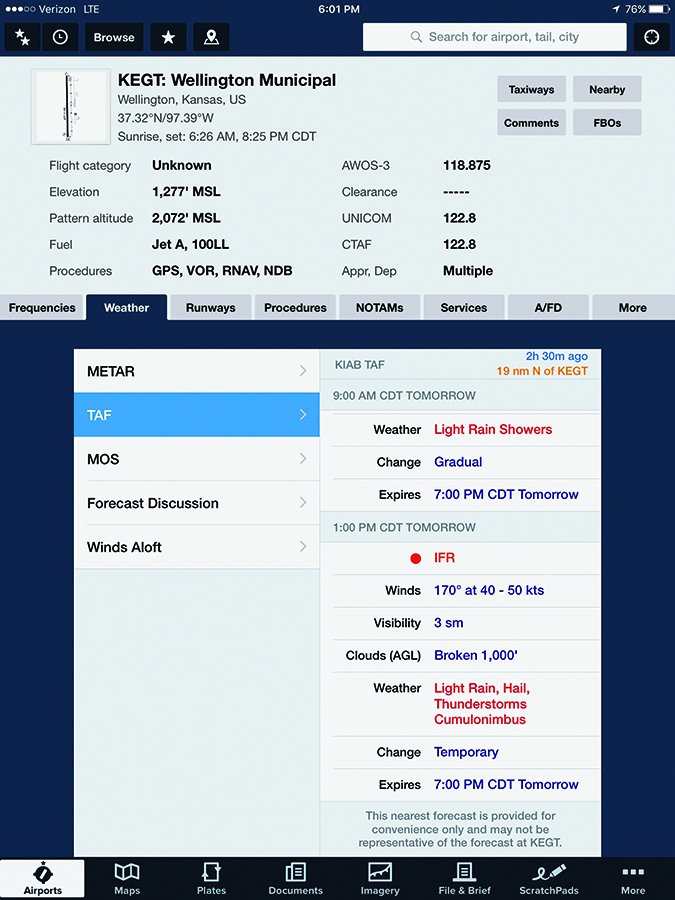

Before the first leg of my eight-hour day of flying, I did my preflight with extra care and was delayed by the fact my tailwheel tire was flat and needed to be changed. After installing the spare and making a logbook entry, I put away the tools, completed my walk-around and finally clicked the “Brief” button on my iPad. My planned route was already entered into ForeFlight, and the system quickly kicked back a nicely formatted, up-to-date briefing with a timestamp telling me it was fresh data. My hypothesis was looking pretty good.

ForeFlight’s previous software version provided a simple table of data, much of it still in teletype style. But the software developers had taken it up a notch and created an interface with graphics and a “next” button that literally stepped me through briefing information, starting with adverse conditions, synopsis, current weather, forecasts, Notams, etc. In truth, I was stunned. The new version of the software was so much better than I expected. The system literally guided me screen by screen through the briefing with the added bonus of graphical depictions.

As I dialed Flight Service, I felt sorry for the poor soul at LockMart who would answer my call. If this was a contest, they were already one goal behind and hadn’t even suited up. The familiar robot answered, I requested a briefer and named my departure state. I listened to the goofy tones indicating the robot was fetching a human. My wait was just long enough to feel slow, but not so long to make me impatient. When a friendly, service-oriented voice answered, I gave my N-number and was prompted to provide the route of flight, proposed altitude, time en route and departure time. I leaned back and waited for the magic to happen.

The briefer immediately put points on the board: “There are no adverse conditions along the route and no TFRs. Most of the route is dominated by a ridge of high pressure with dry and stable air on the western portion, but toward the eastern end of the route it looks like possible light rain as you cross into an area of moisture flowing into the Midwest from strong southerly flow coming from the Gulf of Mexico, but conditions will remain VFR.”

Those two sentences told me more about the big picture of my flight than I gleaned from my self-briefing. All the component weather parts in the self-briefing were turned into a meaningful whole. It’s easy to get lost in a forest of data when there’s so much of it. So score a big goal for Flight Service. That’s what I want when I call a briefer, someone who can walk me past all the trees and show me the forest.

After stepping through the synopsis and current weather, he quickly turned to the winds aloft forecast bracketing my chosen altitude. I had already glanced at the winds and knew they are typically good flying from west to east, but the tire change had distracted me from looking at the afternoon forecast.

The briefer noted that the higher I went, the more favorably the winds aligned with my route. And if I climbed another 3000 feet, they shifted in direction from 250 to 280. Another score, and a bonus point. That information gave me the incentive to get out my portable O2 bottle so I could get a bit more groundspeed.

Flight Service’s Evolution

Not unlike the industry it supports, the Flight Service function has changed greatly over the years. When there once were more than 300 Flight Service Stations scattered throughout the U.S., making and disseminating weather observations, now there only are three hubs and three satellite facilities outside of Alaska. The equipment has changed a bit, also.

The MEGO Factor is High

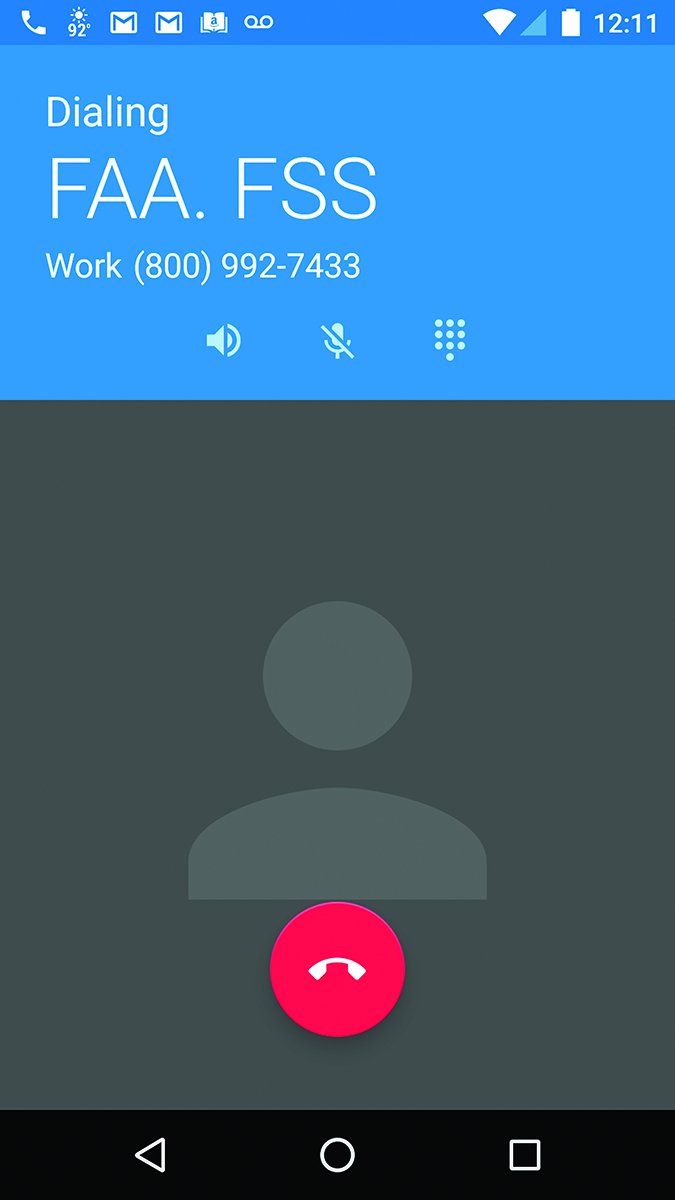

Then the briefer stepped into the part that tends to make me MEGO (i.e., my eyes glaze over): Notams. I freely admit that when I’m in touch with my inner Inhofe, I rather hurriedly self-brief this part. “Your route passes over the Camp Guernsey R-7001 Restricted Area. Let’s see if that is active…hmm, looks like there will be live-fire exercises going on when you are over that area, so I would definitely steer clear of that airspace.”

Whoops, I had missed that one. Not that I would have ventured into it during my flight, but my route literally hugged it, and I had planned to fly a great circle with little deviation. Hearing about live-fire practice in a restricted area painted a bit more vivid picture than the blue box labeled R-7001. Later, in flight, I was motivated to give Camp Guernsey a bit wider berth than normal.

Finally, the briefer got to Notams for the destination airport of Miami County, Kansas (K81) and noted there was a Notam for a runway closure the next morning. My plan was to depart the following morning so that was a rather important catch. As it turned out, it was temporary closure for mowing the grass runway, but it easily could have been some form of major construction that affected my plans or the safety of ground operations. Also, had I departed on the grass runway the next morning, I could have unwittingly crossed paths with a tractor and bush hog.

So, with my first phone call, my faith in Flight Service was restored. I learned more salient information in less time by having an expert walk me through the several critical aspects of a long but fair-weather flight. They did their job by pointing out the changes in the system that are hard to keep up with. That’s a major reason Flight Service exists.

Sweet Spot

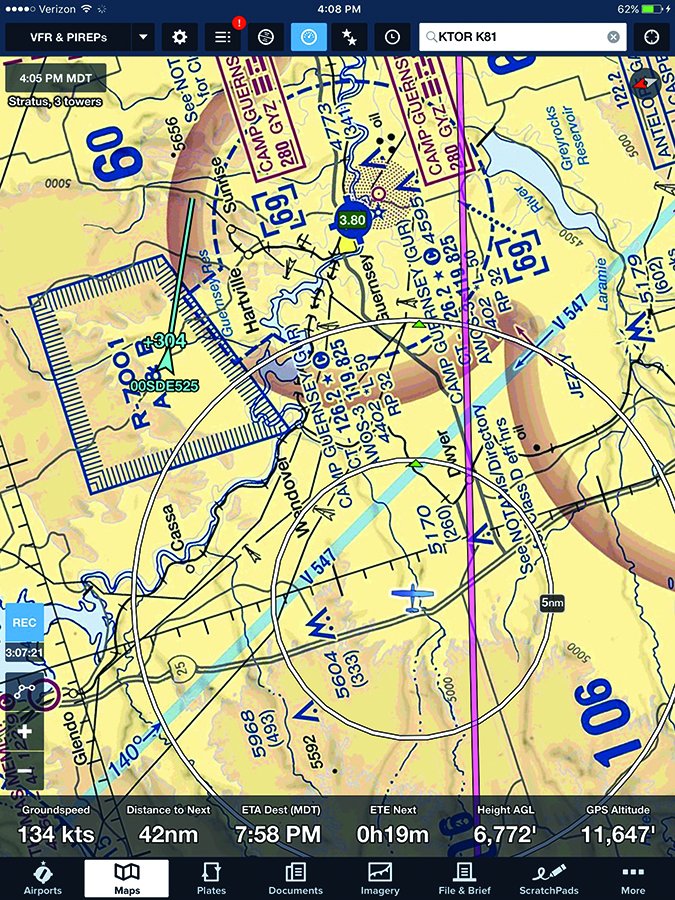

My trip continued, but the weather became increasingly challenging. As each briefer gave me their own take on the weather system, a bit of their insight began to rub off. Between FSS and my concurrent self-briefings with my iPad, I had a decent sense of the synoptic weather picture by the time I was ready to leave Dallas. I was beginning to find the sweet spot of combining a phone briefing with my self-briefing.

I noticed that as my flight planning shifted from VFR to IFR, I had mixed results with briefers. Most of my briefings proved to be like the first one, offering insights into the larger weather systems, trends that would affect my routing and timing, and Notams I may have missed. Oddly, the least satisfying briefing was the one leading into my most challenging flight: departing Dallas.

Mid-morning on the day of my departure, the Dallas area was VFR, but ceilings were dropping. My goal was to pick a route that would keep me in VMC and ride it as far north into Oklahoma as possible. It was going to be a three-hour flight and I wanted to stay visual as long as possible.

Unfortunately I got one of those Flight Service briefers who was going to read TAFs to me instead of the trained weather insights that would be helpful. I also could tell she was suspicious of my motives. Her tone told me that she thought my intention was simply to scud run.

While we were talking, I was looking at the radar and ceilings on my iPad. I could see several lanes where the ceilings seemed to be holding and wanted her insights on how far north I could go before they played out. If I tracked along the front, could I buy a bit more time in visual conditions? As I probed to find out where the ceilings would be highest and hold the longest, she kept coming back with the mantra, “VFR not recommended.” I get that, but for the love of 100LL, throw me a bone.

I eventually gave up and filed an IFR flight plan on my iPad and resigned myself to climbing into the soup right from the start. It is easier to leave Bravo airspace IFR, but I do not take three hours of single-pilot, no-autopilot IFR lightly. Hence my attempt to buy a portion of the flight in VMC. But it wasn’t worth the time or energy to briefer-shop for someone who could advise me onto a MVFR route that to them clearly smelled of scud-running. The clock was ticking and I needed to get launched before it started getting convective.

I self-briefed my IFR departure and again called FSS for another full briefing. This time, I only asked IFR questions so I got a decent briefing that told me my plan was doable. There’d be lots of rain and clouds, but no thunderstorms if I was airborne within the hour.

After stopping in Kansas City, I finished the route back to Idaho with one more instrument approach logged and consistently good phone briefings. I eventually got in the rhythm of pulling up my iPad briefing and listening to the briefer as I stepped through the material in front of me. By telling the briefer I was looking at the same charts they had, we could dispense with the text descriptions of geometric boxes. When they got to the obstructions, I told them I wasn’t a helicopter or cropduster so I could wave them off if the obstruction wasn’t less than five miles from the airport of interest.

With about 24 hours of cross-country flight time logged on this trip, including 2.2 hours of IMC, my experiment comparing phone briefings to self-briefings was complete. I am no longer as jaundiced by the first, and no longer as confident in my interpretations of the second. On the other hand, will I call FSS for my 20-minute joy ride in the Cub? Probably not, but anything that legitimately fits into the category of a cross-country flight warrants the call.

Mike Hart is an Idaho-based, instrument-rated commercial pilot, and proud owner of a 1946 Piper J-3 Cub and a Cessna 180. He also is the Idaho liaison to the Recreational Aviation Foundation.