by Ken Ibold

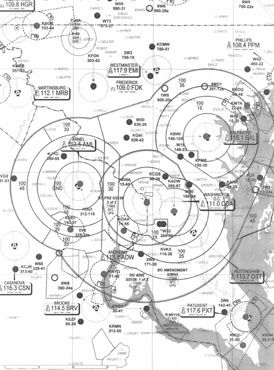

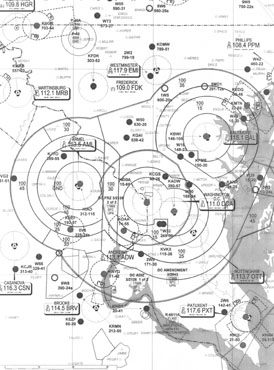

This month the Washington ADIZ marks its first birthday, much to the chagrin of pilots flying in the area. In that year, there have been an average of more than three airspace busts per day.

A thousand times in the past year, pilots have blundered into well marked and highly regulated airspace, doubtlessly leading some in power to wonder if general aviation pilots are nothing more than a bunch of buffoons who deserve little freedom and even less trust. Across the nation, temporary flight restrictions pop up at times and locations that seem to be tied more to issues of politics than security.

Faced with this new arsenal of bureaucratic threats, most pilots have responded with increased dedication to navigation and pre-departure information gathering. Despite that, the FAAs regional offices and legal staff are swamped with enforcement cases brought on by pilots who bust the DC ADIZ and other sections of newly restricted airspace.

Thats the bad news. The good news is in the vast majority of cases, the offending pilots are tracked and told to turn themselves in to the FAA after landing. Only a very small number involve military aircraft or gun-toting law enforcement types on the ramp at shutdown, according to FAA sources. Numbers of interceptions and any security risks so far identified are much less certain. Officials at Norad and the Transportation Security Administration, respectively, have so far declined to outline the details associated with noncompliance by general aviation pilots.

The pilots who do inadvertently stray across the line on the map enter the world of FAA enforcement. Here, to paraphrase George Orwell, all pilots are created equal, but some are more equal than others.

The TFR Players

First, the kind of violation has a tremendous impact on the penalty involved. Although the FAAs official position is that penalties can range from a warning letter to revocation, with most being a suspension of 30 to 90 days, discussions with aviation attorneys show a slightly different reality.

In one category are the TFRs associated with stadiums and the Disney theme parks in California and Florida. These TFRs are now codified by acts of congress and insiders say their sole purpose was to control banner tow flights.

While the aim of getting rid of the banner tows seems to have been the desire to prevent distraction, avoid dilution of advertising dollars or put the crowds of airplane-phobic customers at ease, in practice these are viewed by many controllers as economic TFRs and subject to a different set of unofficial rules.

Although officially controllers are supposed to report any TFR violation, some controllers say pilots who violate one of these flight-restricted areas get a free pass unless they are banner tow operators who clearly know better.

In such cases, a controller who is contacted by a VFR pilot in the offending space simply doesnt hear the call until the airplane is clear, then works the arrival normally. If the airplane is IFR or in contact as it nears the space, then it is considered under ATC and thereby is allowed into the space. Time permitting, the controller might give the pilot vectors around it, but this is scarcely a priority.

In the next category are what might be considered security TFRs. These exist over a handful of military facilities. Although some pilots regard nuclear power plants as falling into this category, at this point there are no TFRs associated with nuclear plants.

At the request of the Department of Energy, the FAA did issue TFRs around nuke power plants and other nuclear facilities in the late-2001 wave of aviation restrictions, but those are long gone. There remains an FAA advisory that pilots should not loiter near them, but that advisory does not carry the weight of either law of administrative penalty.

The third category includes what might be considered traditional TFRs. These are areas involving aerial firefighting operations, space launches, laser shows and other spots where there is a danger to transient pilots.

Finally, there are political TFRs. Into this category fall the DC ADIZ, the presidential pop-up restrictions, downtown Chicago, and the shrinking and expanding space around Camp David and the presidents ranch near Crawford, Texas.

In the first 11 months of 2003, the FAA says there were 83 violations prohibited space around Camp David and 136 violations in Crawford. These numbers include the small prohibited space and the larger TFR space that exists around it when the president is there.

Enforcement

The FAA, citing security reasons, refuses to discuss how violators of the DC ADIZ are detected and tracked, but you can bet AWACS aircraft have something to do with it. Its also reasonable to assume that military hardware is on the job when the president is traveling.

But in most cases, its up to ATC radar to detect transgressors and controllers to identify the offender. Even so, generally the pilot is simply honor-bound to call a toll-free number after landing.

In a very small minority of cases, local law enforcement is waiting when the pilot lands. The pilot is questioned, perhaps arrested, and then released. At that point, the administrative wheels begin to turn.

When a violation is reported to the FAA, an inspector from the local Flight Standards District Office investigates whether there was, in fact, a violation. If that inspector finds no violation, the case is quietly closed.

If there was, in fact, a violation, the inspector has a set of guidelines to determine whether administrative action or legal action is most appropriate. Administrative action may include a letter of warning, a letter of correction or a requirement for remedial training. Legal action can include a civil penalty involving a fine up to $50,000 or certificate action, including suspension or revocation.

The inspector, however, can only recommend these courses of action. Its up to the FAAs legal staff to make them happen. That is where, say aviation lawyers we talked to, reality and politics butt heads.

The caseload created by the flood of TFRs has swamped FAA lawyers, creating a backlog of more than half a year before the initial assessment can even be made over what avenue to pursue. The lawyers involved have other responsibilities – there are none whose job is strictly to handle violations – and so the cases take on a de facto priority given how high a profile they have and how significant the violation is deemed to be.

At the same time, tight fiscal restraints at the FAA demand cases get disposed of efficiently – and that means without litigation.

An anecdotal inquiry of several aviation attorneys involved with defending pilots generates evidence that a pilot involved with a minor violation who hires a blustery attorney can easily get off with a mere 15-day suspension. Threaten enough – read: spend more on your legal bill – and its not too hard to whittle that down to remedial training.

However, these minor penalties apply only to the violations seen by the FAA lawyer involved as the least egregious violations. That means they likely will not be available to pilots who bust the DC ADIZ or one of the other politically sensitive restricted areas. They also will not be available to those who violate traditional TFRs and pose actual safety risk to themselves or others.

In those cases, the pilot who gets off with a 30-day suspension should consider himself lucky, the private lawyers say.

Of course, the easiest thing to do is simply avoid busting the TFRs in the first place. While that may be easier said than done, all it really requires you to do is hold yourself to the same kind of navigational standard you might use to avoid or operate in Class B airspace, and that doesnt seem to be creating nearly as many problems as areas of temporary flight restrictions that, in practice, dont seem so temporary at all.

Also With This Article

“Call This Number After Landing …”

“The Enforcement Process.”