Our freedom to fly is a gift. The FAA provides pilots with reasonable rules and regulations, and a lot of discretion to determine the proper course of action. Sometimes the rules are not applicable in all circumstances, or for all pilots and aircraft, so what may seem to be perfectly legal isn’t safe, and vice versa. In other words, pilots also are given the freedom to be stupid.

The visibility and cloud clearance regulation is one of those reasonable sets of rules. They make sense; you should have greater visibility at night and at altitude, though they include just enough variations for circumstances— airspace, altitude, and time of day—to require printed reminders on kneeboards and lens cloths. I do my best to stay the proper distances from clouds, though I can’t think of many circumstances where I was deeply concerned about my specific cloud clearances either for legal or safety reasons. I am primarily concerned with visibility. When it’s marginal, the rules can seem a bit hazy, but the hazards should be clear as a bell.

On the Margins

There are several hazards associated with low visibilities, of which the most benign is simply getting lost. When I was ready for my solo cross-country back in August 1982, it was during a hot and humid summer when the entire Midwest, from Oklahoma to Iowa, was socked in with visibilities holding at three miles in haze. This was long before the internet era, a time when you still had to call Flight Service for briefings to get the visibilities and forecasts along the route.

My instructor wanted me to have at least five miles’ visibility, but with the haze holding, he decided I could deal and sent me on my way. My route was from my home airport in Miami County, Kan., to Beatrice, Neb., then on to Salina, Kan, and back home. It took me 5.2 hours in a Cherokee 140, and I still remember the flight, not because of the scenery, but the lack of it. With only three miles’ visibility, I had to basically stay on top of my headings by flying the directional gyro rather than orienting on some point in the distance. The cities and checkpoints quickly appeared and disappeared.

It wasn’t instrument flight by any stretch, but it was the kind of flying that if I didn’t stay on my planned course, I could easily stray from my carefully planned route. At one point, I lost track of which specific little town I had just passed and which was coming up next. I had to triangulate my position on two VORs to reconfirm my location on the sectional, and I was prepared to drop down to confirm the next city name on its water tower, but my VOR trick worked. I was reoriented and back on track. With that, I was back in the game and completed the trip with no further issues. (These days, of course, being forced to shoot cross-radials from two VORs to pinpoint your position means you may have other problems.)

As visibility drops, you lose the horizon and must increasingly rely on your instruments to stay on course. In flat terrain, that isn’t the worst scenario. It is not unheard of for pilots to land at an airstrip with the simple question, “Where exactly am I?” It is an embarrassing question, but not necessarily a fatal one. It’s not as bad as “What time zone is this?” but both confess to a lack of preparation. When I took my checkride over the plains of Kansas and Nebraska, I knew if I ended up off-course, there wasn’t any terrain within the airplane’s range that would rise up to greet me.

Fast forward to my current job flying in the mountains and canyons of Idaho. With only three miles’ visibility, even pilots with thousands of hours legitimately choose not to take VFR flights into the backcountry. Three miles in Kansas and Nebraska may be reasonable for a student pilot, but the same conditions in the mountains is a totally different animal when granite is walling you in.

The biggest hazards of unclear skies are controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) and spatial disorientation, not necessarily in that order. One mile and clear of clouds is perfectly legal in certain airspace, but it can be absolutely insane if you are flying below the level of nearby terrain in narrow canyons where, on a good day, you get nervous doing a 180. Even the most experienced pilots will hesitate to drop into smoky canyons. Those are the times when flying is a fool’s errand.

Tools You Can Use

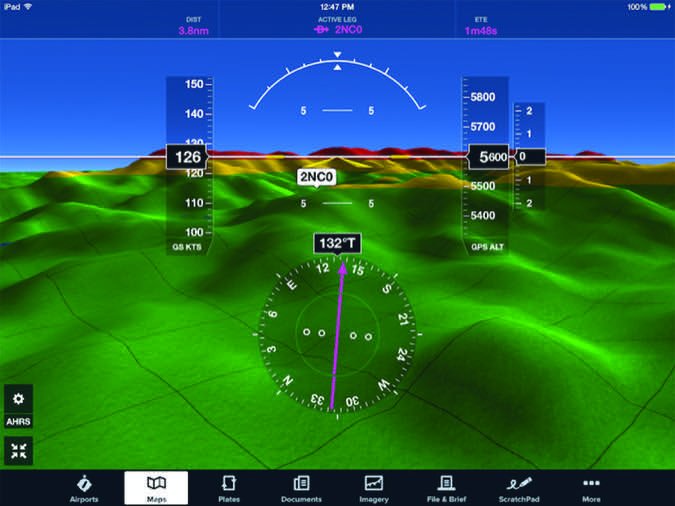

The toys we have in the cockpit these days—like any other form of magic—are a blessing and a curse. Because applications like synthetic vision exist, they can give us an extra helping of situational awareness, something we never get enough of. They might even help get us out of a situation we shouldn’t be in, or didn’t ask for.

But they also can entice us into doing stuff we might not otherwise do. It’s not all one big video game. Products with capabilities like ForeFlight, at right, Garmin Pilot and many more are so good it might seem that way to some.

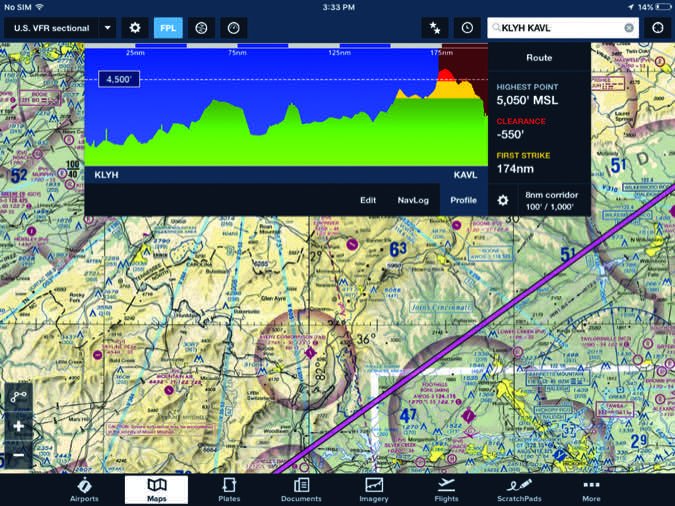

The good news is those same products can help us avoid situations where we need that capability. The top-of-the-line EFB apps also are smart enough to show us how and where we’ll smack into something if we keep going. Foreflight’s profile view is shown at bottom. — J.B.

What About Night Low-Viz Flying?

Holy Cow! If you think you can fly safely with three miles’ visibility on a moonless night without strong instrument skills, you are a good candidate for a Darwin Award. I have flown my share of night VFR through scattered cloud layers. It wasn’t fun. One time, I could see the city ahead, then it was obscured, then visible again, and over, and over—on and off like a turn signal. It was nerve-wracking. I terminated the flight and chose a nice hotel over the stress of the cockpit.

By my reckoning, low-visibility night ops are for IFR pilots, flying instrument-equipped airplanes. Flying with clouds and maintaining cloud clearances and visibilities in the daytime is challenging enough, especially at a relative high cruise speed. At night? VFR? Fuggedaboutit. There’s a reason the FARs require greater visibility to maintain VFR at night in uncontrolled airspace, and that special VFR at night requires an IFR-qualified airplane and an instrument-current pilot.

The CFIT Risk

This summer, there was a series of days where widespread visibilities over popular destinations were often less than three miles. The backcountry frequency was abuzz with pilots asking where the smoke was thick and where it was penetrable. Many had to turn to driving passengers, which was painfully slow, but at least safe. Many backcountry flights were simply canceled.

The biggest danger of dropping beneath terrain in low visibility is failing to see the terrain in front of you before you can turn away. In a plane traveling at 120 mph, a pilot in one statute mile visibility can only see 30 seconds into the future. At 90 mph, we only get 45 seconds. That’s enough time for your eyes to briefly scan instruments and then return to looking forward. Meanwhile, you better know exactly where you are with respect to terrain at all times. This kind of flying is at the cognitive limits of even the best brains, and there is little room for error.

If you take terrain out of the picture, you are in a marginally better position, but you still have less than a minute of decision space in front of you. Do you really have the perceptive skills to detect when one mile of visibility degrades to less than a mile?

I recently launched out of Salmon, Idaho, with three miles of visibility due to smoke and headed to Idaho Falls, where there was a whopping five miles. I was familiar with the route, but decided to gain a bit more altitude to have a safety buffer. As I climbed, I found myself deeper in the smoke. It definitely was less than three miles’ visibility, but it seemed worth it to trade forward visibility for terrain clearance. I liked my trade-off since I knew I was headed toward better conditions, and I knew I could descend slightly to gain more visibility if needed.

Maintaining Control In Marginal VMC

It’s not impossible to fly right at the legal minimum flight visibility. To do it correctly, consider:

Slow Down

Life comes at you fast in low visibility. You’ll have more time to see, plan for and avoid obstacles or traffic if you just slow down from your normal cruise speed.

Get Some Altitude

You must be at an altitude above the highest obstacle in the area. Use a sectional chart’s maximum elevation figure, the big blue numbers. In mountainous areas, you might as well go IFR.

This Is Pilotage

This isn’t time to follow the magenta line. Look outside the airplane, and glance inside only occasionally.

Spatial Disorientation

Basically, I was flying on instruments, with a need to keep an eye out for obstacles and traffic. The downside was that dividing my attention had me fighting low visibility’s second killer: spatial disorientation. It’s one thing to fly instruments when you know ATC is covering terrain and traffic, and your eyes are on the gauges. But in low visibility with no clear horizon, you need a good instrument scan, while occasionally verifying the outside world still has legal visibility and that you’re clear of terrain. Glances away from the instruments are hell. They actually make it harder to stay oriented.

Pilots without instrument training should studiously avoid visibilities so low that they eliminate a clear horizon line. With no horizon, you really must depend on instruments, and without the skill, experience and mental training, you run the risk of disorientation. Even then, you can become disoriented. I got the leans on my flight from Salmon to Idaho Falls. It felt like I was in a turn, but the instruments said I was straight and level. This happens, but without the training, the leans quickly become a death spiral. At 120 mph, you only have a minute or two to recover.

SVFR And Contact Approaches

You might think low-visibility flight only occurs in uncontrolled, or Class G, airspace. But the FARs allow one mile and clear of clouds in controlled airpace, too. Both of these clearances must be requested; ATC will not offer them.

Special VFR

An SVFR clearance is available below 10,000 feet msl and within the lateral boundaries of the controlled airspace designated to the surface for an airport. Fixed-wing night SVFR requires an instrument airplane and IFR pilot. An SVFR clearance allows fixed-wing operations in one-mile visibility and clear of clouds.

Contact Approach

The contact approach allows pilots operating IFR, clear of clouds and with at least one mile of flight visibility to proceed to the destination airport in those conditions. The pilot assumes the responsibility for obstruction clearance, similar to a visual approach.

Personal Minimums

The FAA is big on people having personal minimums—simple, discreet numbers that are either in or out of your comfort zone. That’s easy when you are new to flying and still wiring in your general comfort levels. But as you gain more experience, it gets harder. One mile and clear of clouds? Sure, I’m game…sometimes. I have to ask: Why is the visibility one mile? Smoke? A layer of fog with clear blue sky above? What plane am I flying? Do I like the avionics stack? Am I headed out of the crap and toward something better? Where am I, Kansas or Idaho?

The more you know as a pilot, the more tempted you are to consider marginal visibilities. But the more you know, the more you should realize how unforgiving the edges of that envelope can be. If you are an IFR pilot, it can be even more difficult. Being competent shooting an ILS down to minimums doesn’t translate to dividing attention between a good instrument scan and the occasional verification that granite isn’t 30 seconds away from your windshield.

Even when visibility is legal, it may not be reasonable. When the day comes that you are in “one mile, clear of clouds,” and you’ve checked and double-checked your thinking, ask yourself, “Do you feel lucky, punk?” Your answer should be, “A pilot’s gotta know his limits.”

Mike Hart flies his Piper J3 Cub and Cessna 180 when he’s not schlepping people and their gear. He’s also the Idaho State Liaison for the Recreational Aviation Foundation.