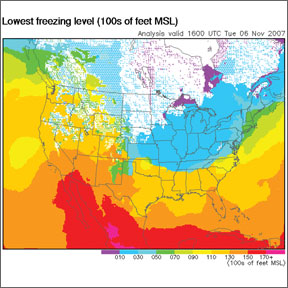

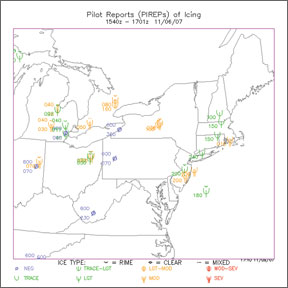

Aircraft utility can go down significantly in cold weather. Adverse weather is more common and tenacious than in warmer months, and along with the fog, low clouds and wind, there is often the threat of airframe ice. Yet we still want, and sometimes feel we need, to fly. How can we balance the possibility of airframe ice with the utility of our airplanes? How do the experts-those “on a mission” with their airplanes-predict, avoid and Gary Watt 288 escape airframe ice? To answer these questions I spoke with professionals who slog through the weather every day (and night), flying high priority aeromedical, charter and air cargo in piston, turboprop and small jet aircraft. Mixed Fleet, Common Rules Marvin Hesket is chief pilot for Midwest Corporate Aviation in Wichita, Kan., an air charter operation that also has serviced aeromedical flight contracts. The MCA fleet includes a mix of Beech Barons, King Airs and Learjets, but similar rules for flying in ice apply to each. Forty years ago Marvin flew mail between Reno and Las Vegas in a Piper Aztec. He turned around or landed at an alternate often in wintry night skies, “maybe more often than the Post Office liked,” because of ice. The first ice trick he learned was to turn on the airplanes landing lights in cold IMC. “If snow doesnt sparkle in the lights,” he quips, “it was going to stick” to the airframe. He still uses this technique in Barons to Learjets, and teaches his new hires to do the same. Marvin emphasizes aircraft manufactures data for making ice-related decisions. Some of his Barons are certified for flight in icing conditions (so-called “known ice”). The King Airs and Lears of course carry “known ice” certification. All have limitations on operable equipment, minimum airspeeds in ice and the type and amount of ice, in which each is certified to fly. The King Airs, for instance, are certified for continuous “trace” to light icing in cruise flight, and moderate icing in short climbs or descents at the published minimum ice penetration airspeed. Marvins pilots “dig into the manuals” because “each airplane has its quirks” about ice certification. “We tend to cancel a lot of trips in the King Airs and Barons because of ice,” Marvin says. Even in the jets, “avoidance is our main key.” Marvin teaches pilots to “believe the 288 forecast” but “call ahead” to confirm conditions and talk to pilots who have just landed. He doesnt see a lot of correlation between online Forecast Icing Potential (FIP) charts and actual icing conditions he encounters, but puts great store in pilot reports (Pireps) from other pilots, knowing the freezing level and the weather-producing mechanism before taking off. Marvin plans alternate airports short of his destination near his route of flight so he doesnt have to continue beyond his goal if he encounters ice. He disciplines his pilots to “do what our training tells us to do”-for instance, avoid temptation to launch in the Baron or King Air when cloud tops are at 3000 feet, sky clear above, but moderate ice is reported in the clouds. “You never know how long you might have to be down in it.” Further, there is great “distraction when on the approach, flying dirty, low and slow,” distraction that may prevent a pilot from noticing ice accumulation or its aerodynamic effects. Marvin insists his pilots turn on all anti-ice equipment on all flights, year round. “Its easier to stay in the habit of using ice protection summer or winter, so you wont forget it on a cold, dark night.” Regardless of the airplane, Marvins rule is “do not stay in sustained ice” accumulation. Not only are the airframe effects hazardous, but antenna ice and static electricity build-up affects communications and navigation radios. “Use your thermometer, landing lights and eyeballs” to detect and avoid ice, he says, and “know your escape plan before you go” into potential icing conditions. 288 Does this 40-year veteran of ice encounters have some limitations on where hell take an ice-certified airplane? Absolutely, he says. “We dont go anywhere near anything to do with freezing rain. Dont count on being able to outclimb freezing rain” into warmer air. “You may think you can climb out but youll likely get too heavy, fast. Use your time instead to turn around, and land and wait it out if you have to.” Marvin also strongly recommends staying on top of cloud layers as long as possible, then making a straight-in, “penetrating” descent. Do not to accept long vectors in IMC when the air is cold, and decline approaches requiring procedure turns or course reversals. Tell, dont ask, ATC to let you stay above clouds as long as possible. Also, decline circling approaches in potential icing conditions. “The worst ice I ever had was in a Learjet on a circling approach in relatively benign winter weather,” he says. Marvins final bit of advice applies beyond just ice avoidance. “Every airport has a road,” he reminds us. “Drive down that road and eventually youll get to another airport.” His point is that there are conditions, notably ice, when driving is far 287 preferable to flying. Great Lakes Charter Lee Cobb has flown charter out of Macomb, Ill., since 1981. He currently flies King Air 200s and employs five pilots. Like Marvin Hesket, Lee thinks Pireps are the best possible briefing product for ice avoidance. He especially likes “early morning Pireps” because they may indicate the general tone of weather for the day. Lee expects his pilots to be students of weather, to understand not only what the weather is, but what itll become and why it will be that way. He eschews hard-and-fast icing rules, because “every day is different…what worked yesterday might not work today.” He often sees what he considers “unacceptable risks” taken by pilots in ice, and offers this advice: Know the freezing level in your area at all times. Pop the boots (or activate other deicing equipment) just prior to the final approach fix (FAF) inbound. Fly a stabilized approach from the FAF to the runway or missed approach point. Do not attempt multiple approaches in icing conditions. If you miss an approach, proceed directly to an ice-free alternate. Highest Priority “Its a mistake to say fixed-wing aeromedical flights are high priority,” says Harrel Timmons, who owns an air taxi/aeromedical system in Galesburg, Ill. His three-FBO network flies Cessna 310s, 303s, 401s, Citations and a Lear 35. “Fixed-wing patients arent flown until theyre stable.” The highest-priority flights, Harrel says, are those carrying organs for transplant. In the icy Great Lakes region, “organ flights are the biggest part of our business,” he reports. “If you fly a lot you will get into icing.” But Harrel is not cavalier about the threat. “If you get into ice,” he continues, “you will also remember the date, the hour and the location of your worst ice encounter.” The best defense against ice is knowledge. “Below 40 deg. F,” Harrel says, “all forecasts say icing. They err way on the side of caution.” This creates a “handicap to trying to use the system effectively.” The “absolute best protection” for a pilot is to “know the weather system, what causes ice, and know a way out” before ever taking off. Harrels advice: “I dont care if youre in a known-icing airplane or not, the best thing to do is escape.” Even with top-of-the-line deicing equipment “youre going to get performance degradation.” The worst icing conditions, according to Harrel, are in stationary fronts. Maximum icing, in his experience, happens between 34 deg. F and 25 deg. F; in stable air below about 15 deg. F to 20 deg. F he says ice will “sublimate as fast as it accumulates.” As soon as ice begins to form, Harrel says, “go up”-youll climb out of icing conditions, on top of clouds, or into air thats outside the icing temperature range. Harrel continues: “Youre not going to know the full [weather] situation from weather reports.” A good weather pilot needs to know what causes ice to form, and characteristics of transfer of energy as water changes from liquid to solid and back again. “The number one rule is dont panic;” the fastest avoidance is to “turn 90 degrees” to the threat. “I could talk for hours about avoiding ice,” Harrel exclaims-and I believe him. Army Props Neil Pobanz runs a small FBO in Lacon, Ill. Talk to him for a minute and youll understand why he was inducted into the Illinois Aviation Hall of Fame. Neil is passionate about aviation, and has the rare ability to patiently educate others. Markus Herzig 288 For many years Neil was chief of standardization for the U.S. Army Material Commands fleet of Beech Barons, Queen Airs, Twin Beeches and King Airs. They flew a lot of high-priority missions. How did the Army deal with ice? “We watched the forecasts, and especially Pireps very closely,” says Neil. He also taught his pilots to evaluate Pireps by the type of aircraft filing the report. “If the airlines even reported ice,” he relates, “then thats not the place for me.” “Approach would drop you down” into the clouds, he said, “and that was the place wed get a lot of ice.” Neils strategy was to stay on top of cloud layers as long as possible, then descend continuously through the icing layer. Ice accident scenarios, Neil said, usually involved some maneuver requiring long exposure to low-altitude icing levels, such as a DME arc. Light Freight Part 135 freight has the greatest notoriety for flying in ice. Chad Moyer is Director of Safety and interim Director of Training for Ohio-based AirNet, one of the largest light airplane cargo operations in the world. The majority of AirNets airplanes, from piston twins through Learjets, are “known-ice” certified. Chad spends a great deal of time in new-hire orientation teaching ice prediction and performance, a philosophy he sums up in four words: “Get out of it.” Even known-ice certification, he says, “doesnt mean you can sit in it. Its not a golden ticket” to continue in ice. This goes for the jets as well, he says, “although the jets are not in [ice] as long” because of their climb capability. Chad requires his pilots to follow manufacturers guidance for flying in ice, including operable equipment and minimum ice penetration speeds. “They have done the flight testing and the research,” he says. “You dont have to be a test pilot.” Each pilot-in-command is responsible for a go/no-go decision. AirNet uses DUAT for briefings. Like Marvin Hesket in Wichita, Chad says the Forecast Icing Potential (FIP) chart is “not real-world enough” for tactical flight planning. “Its good for a heads up,” he reports, “but once youre up there you depend on Pireps and your own weather judgment.” Most valued, says Chad, are reports of cloud tops. Icing (or negative ice) Pireps are less reliable; because of the localized nature of airframe ice “someone 15 miles ahead of you can report clear of ice, but you can be icing up like a popsicle.” Since many air freight pilots are new to commercial flying and “always want to go,” Chad has to “educate them a lot” about flying in weather. His best advice about icing is that, if you begin to ice up, to “do something-climb, turn, descend or land.” Sometimes “in the terminal area on approach” you might continue if youre sure youll break out well above ground, but otherwise ice means “do something different” to get out of it. Ice is that last great weather unknown. Until we have an ice-detection equivalent of a StormScope or Strikefinder, were at the mercy of the weather briefing system, our airplanes design capabilities and our own weather education. To increase your icing knowledge, take the advice of pilots “on a mission” to fly in potential icing conditions. Tom Turner is a CFII-MEI who frequently writes and lectures on aviation safety.