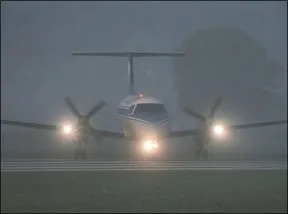

In a perfect world, wed always take off into clear skies. If were going to get any utility out of IFR airplanes, however, there will be times when we take off with reduced visibility and/or low clouds-an instrument departure. Transitioning from visual to instrument flight quickly after liftoff, while accelerating and still close to the ground, takes precision to be performed safely. How do pilots “on a mission” to take off into low ceilings or visibility plan and execute a safe departure?

Into Veiled Skies

288

Dave Dewhirst runs Wichita, Kansas-based SABRIS, managing high-performance piston, light twin and light turbine aircraft around the country, with a network of mechanics and flight instructors helping assure safe operation by pilots in the managed fleet. The first key to safe IFR departures, says Dewhirst, is to “take a deep breath” before taxiing onto the runway, ensuring theres time to make certain all checklist items are complete. This includes briefing the departure, briefing passengers, along with all those little things like navigation and transponder settings, security of doors and windows, checking for seat belts closed in the door to flap against the fuselage in flight, and the like.

The idea is to prevent distractions on takeoff and in the first stage of climb. Dewhirsts philosophy is that “Im not aborting the takeoff, and Im not coming back” to the departure airport because of something that should have been configured or checked before taking the runway.

Richard Bertoli is chief pilot for Airshares Elite, a fractional ownership program offering Cirrus SR22s in 17 locations around the U.S. Extensive initial and recurrent pilot training is required for all program members, and in fact is “one of the reasons people join,” according to Bertoli. Planning and executing an instrument departure, Bertoli asserts, should be no different that a VFR launch-hes a staunch advocate of standard operating procedures (SOPs) regardless of weather. “Youre going to forget something otherwise,” he says, echoing the idea that good preparation and checklist use should reduce distractions and decrease IFR departure risk.

Chad Pobanz flies a Canadair 604 Challenger for an international manufacturing firm, and learned the trade hauling checks in Shrike Commanders. Pobanz, too, is well indoctrinated in SOPs for all takeoffs, and consequently makes IFR departures pretty much the same as any takeoff.

What specific recommendations do these experts have for IFR departures?

Lining Up

After all items on the checklists are complete and you line up for takeoff, Dewhirst suggests, set the directional gyro or, if flying with a slaved heading indicator, verify it matches runway heading. This may not always precisely equal the runways numerical designator. All ice protection equipment, if needed for conditions, should be on and checked before taking the runway. Bring up the power about one-third of the way while standing on the brakes for a final pressure/temperature check. He also suggests leaving off the landing and taxi lights so reflections wont create distracting visual cues when you penetrate the cloud deck.

Positive Rate

All three experts are adamant about establishing a pitch attitude that results in something near the “best rate of climb” (VY) speed immediately after lifting off. Dewhirst teaches his pilots to aim for a five-degree pitch attitude, something a little faster than VY in most high-performance piston airplanes (this also provides additional airspeed and therefore control in the event of an engine failure in multi-engine aircraft). Bertoli, his pilots all flying virtually identical Cirrus SR22s, uses 10 degrees nose up on the Primary Flight Display (PFD) attitude indicator-in the SR22 this is “slightly above” VY speed, Bertoli says, and with a 10-inch wide Attitude Deviation Indicator (ADI) its “far easier to fly pitch than [using the PFDs] vertical tape airspeed indicator” for precision. Pobanzs jet uses a higher initial pitch attitude-14 degrees up-but the philosophy is the same. Without a firmly established attitude target, Pobanz notes, pilots tend to “shallow out and not climb” when entering IMC, a potentially disastrous option near the ground.

In any event, and no matter which specific method is used, power plus attitude equals performance. With power set, the proper pitch attitude for initial climb will ensure you achieve your planned climb angle, as long as all other factors (runway length, weight and balance, ice-free airframe, etc.) are met.

Automation

From airline down through personal IFR transportation, the philosophy of aircraft control is trending more and more toward the use of automation. I asked the experts when they think its appropriate to engage the autopilot after launching into IMC.

Dave Dewhirst is emphatic: “No autopilot in the first 60 seconds of flight.” Dewhirst has seen and read about enough autopilot and trim failures, and much more frequently, incomplete or erroneous pilot input into flight-control systems, to trust engaging an autopilot until well clear of the ground.

Bertoli agrees: “As an instructor,” he says, “Im a stickler for adhering to the limitation against engaging the autopilot below 400 agl” thats contained in the Cirrus autopilot supplement. “Some [Airshares Elite pilots and instructors] are even more conservative,” hand-flying to no less than “1000 feet [agl]. “Mastery of the automation is required as much as stick-and-rudder skills,” Bertoli reminds us, so pilot error isnt the cause for this limitation or more conservative personal minimums. Instead, its “the possibility of malfunction” in a flight control system without backups that drives automation conservatism.

Flying a jet in a crew environment, Pobanz relies more fully on automation, engaging the autopilot sooner. But a second set of hands in the cockpit keeps the pilot flying isolated from the task of programming the Flight Management System (FMS). And a second set of eyes makes it more likely any unusual situation will be quickly detected and overcome.

I know from my own experience as a simulator instructor that single-pilot “gear up, autopilot on” pilots tend to be less precise in following an initial heading and clearance. Distraction from programming the autopilot itself degrades precision and (if the sneaky simulator instructor “fails” the autopilot or trim right after takeoff) almost guarantees a crash from lack of time to recognize and recover from an autopilot malfunction.

Theres no question autopilots are a great workload reducer, a tremendous enhancement to the single-pilot cockpit. But first engaging the autopilot, according to these “on a mission” pilots, should wait until the pilot is able to divert attention to the device (or delegate it to a qualified crewmember), allowing time to ensure its properly programmed and there are adequate margins to recover from any malfunctions.

About Flight Directors

Dewhirst says “the jurys still out” on how to use a flight director, if available, during an IFR takeoff. Some pilots advocate setting the heading bug, and therefore the flight director command bars, to the initial heading or route. Others recommend placing the FD in heading mode, with the bug on runway heading so the command bars show a climb straight ahead.

Dewhirst strongly suggests the second technique, to avoid the distraction of command bars indicating a turn when the pilot wants initially to climb straight ahead. Pobanz says his operation uses the “go around” feature of the Challengers FD, which indicates wings level and a 14-degree nose-up attitude (it is, after all, a jet).

The key is to use a FD if it will enhance awareness, but if it introduces a discrepancy between what it indicates and what you need to be doing, youre better off flying “raw data” without it.

Departure Alternate

The Challenger 604s advanced FMS (not to mention its multipilot crew) makes setting up for a return to the departure airport in the event of an abnormality right after takeoff “pretty easy.” The FMS displays approach charts, sets frequencies and figures approach speeds. Pobanzs mount has the power to climb to a safe altitude and then loiter so the crew can figure what to do next. Except in the case of a fire, there are few scenarios where a very rapid return to the departure airport would be required.

Such was not the case when he flew checks in twin Commanders, or in most single-pilot airplanes. “All the usual precautions apply,” says Pobanz. Have the approach charts for your departure airport out and briefed, and load at least the basics of the approach into nav boxes. Bertoli teaches to initially load the localizer frequency in the active portion of the navcoms, to “at least give something to guide you back to the airport” in case of a takeoff abnormality. “Be familiar with the departure airport” before you go, he says-“brief the approach, and check the area for obstacles.”

What happens when the departure airport weather is very low, or is even below arrival minimums? When flying checks Pobanz rarely departed when he had less than arrival minimums. When he did, localized weather conditions often meant his “return” in the event of an unusual situation immediately after takeoff would be at some other, nearby airport.

Section 135.217 of the FARs states, “No person may take off an aircraft under IFR from an airport where weather conditions are at or above takeoff minimums but are below authorized IFR landing minimums unless there is an alternate airport within one hours flying time (at normal cruising speed, in still air) of the airport of departure.

If local fog or low clouds require it, Pobanz would have charts ready and briefed for a nearby airport with better weather or lower instrument approach minimums-a “departure alternate.”

Part 91 pilots do not have regulatory takeoff minima, leaving the decision up to the pilot. “If weather is above minimums,” Dewhirst suggests, “set up for the approach” for the departure airport or a nearby departure alternate. “If weather is below [arrival] minimums its more difficult,” he says. You need to decide “where you are going to go” to better weather. And you “must be able to fly there with whatever abnormality” requires the diversion. Bertoli agrees. He suggests not taking off unless the airport is at better than arrival minimums. But Part 91 lets the pilot-in-command (PIC) decide, he adds.

On a Mission: IFR Departure

Given proper preflight planning, a well-maintained airplane and a proficient pilot, there shouldnt be anything inherently dangerous about taking off into ceiling- and/or visibility-limited skies. We all know, however, that the seemingly limitless variables associated with instrument flight, as well as the environmental, maintenance and pilot-performance unknowns existing at the beginning of a trip make launching into IMC far riskier than a VFR departure (you dont know for certain if the weather is worse than expected, an undetected squawk may reveal itself, or your preflight planning or skills are insufficient until you actually take off). Yet IFR departures are done successfully by the hundreds, if not thousands, every week…using techniques from those “on a mission” to take off into IMC.

Tom Turner is a CFII-MEI who frequently writes and lectures on aviation safety.