Private pilots are required to demonstrate soft-field technique before they earn their certificates. The FAA, however, doesn’t require you to demonstrate that skill on an actual soft field. Perhaps they should. It’s too easy to find examples of pilots filling out reports of accidents and incidents involving unpaved landing surfaces. Based on my experience and those of other pilots like me, there are many novel ways a pilot can screw up when venturing off pavement. Insurance companies know this and often restrict operations to paved runways.

It’s probably not a bad thing that getting off pavement is not as easy as it sounds. Many schools don’t carry insurance for unpaved airstrip operations, and flying clubs often have policies discouraging or outright banning unpaved landings. If you’re an aircraft owner, you may want to look at your insurance policy—it may not cover excursions off the beaten path on private, unpaved or non-FAA listed airstrips. Why are those pesky insurance folks such wet towels when it comes to landing off traditional airstrips?

My First Time

The cacophony was coming from behind and on both sides of me. It was the sound of bending metal, like the banging of sheet metal to create the sound effect of thunder during a theatrical performance. Except the source of the noise was the airplane’s skin. There also was careening and bouncing, and I didn’t feel like I had much directional control. The brakes seemed to do nothing. I was worried the gear would collapse at any moment. I was 18 years old, my private ticket was all of two days old and I was about to crash, or so I thought.

Everything was fine. It was just my first off-pavement landing and I wasn’t prepared for the overwhelming sensory experience of landing on something other than a smooth surface. There is just a very big difference between paved and unpaved surfaces, and this was my first lesson. The only thing reassuring me was the nonchalant look on my instructor’s face, indicating my panic was not shared.

I flew my folks’ Cessna 152 off that runway for another 100 hours and eventually learned where it was rough, where it was prone to hold water and get soggy and where it was a bad idea to venture off the mowed area. I learned to be skeptical of what lurks out of sight.

Disorientation

There most certainly are safety considerations related strictly related to the runway surface itself. But the most important consideration for non-paved runways is their effect on takeoff and landing performance. (I wrote about short fields in February 2014’s issue, and on soft ones in March 2014.) The nice thing about a paved runway is the uniformity of its surface. It’s usually a single color, is level and items that are not part of the runway are on the edges, usually contrasted by a shoulder or other area that help you pick out the obstacle (such as a runway or taxi light) from the background.

If you’re living right, the unpaved runway in your future is smooth grass, like a golf course. For the rest of us, they often vary—some areas greener, some grass taller, some ground bare and other ground with clumps of grass. The visual variations of non-paved runways makes it much easier for objects to hide until you find them with the prop. It also can make it hard to stay on the centerline, because, duh, there isn’t one.

The lack of uniformity and clear markings at unpaved airstrips is disorienting and can lead to pilots losing track of the runway center and veering off into the weeds on either side during takeoff or landing. It also can lead to rolling off the runway and into a ditch while looking for the tiedown area or the best place to exit the runway.

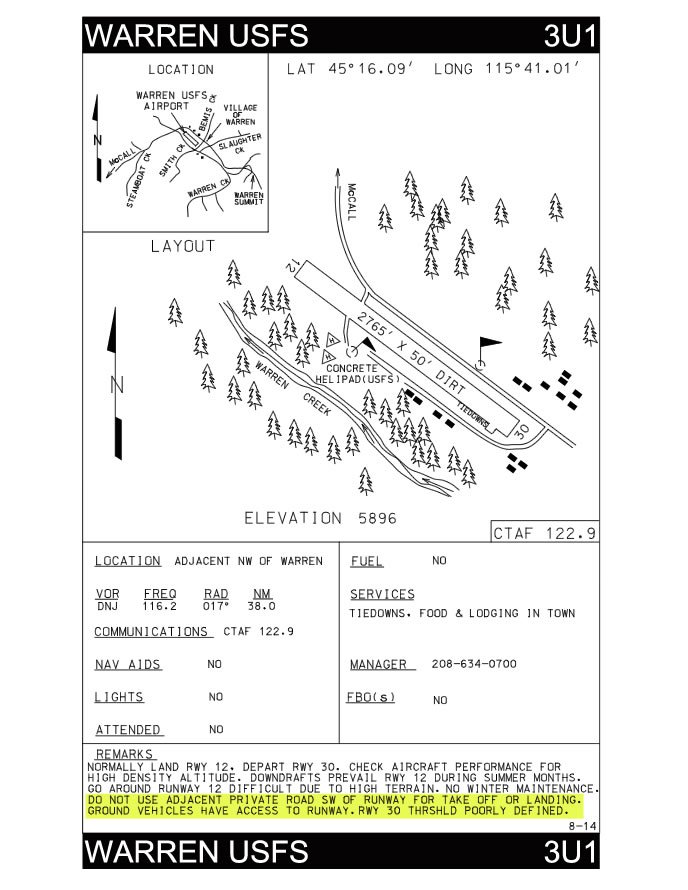

If you’re planning to use an unpaved strip, you need information perhaps not available from the usual suspects. The FAA’s and other databases may tell you things like runway orientation and field elevation, but the best way of knowing where to park, or the best direction from which to approach, and why, or how soft the strip can get after it rains comes from local knowledge. Pick up the phone and ask.

If there’s no one to ask, get whatever you need from whatever sources you can, including a low pass over the strip. Don’t fixate on things like wind direction or obstacles, and don’t forget to look at the runway surface and the logical approach and departure paths. Figure out the best place to park (Hint: It’s not at either end of the runway) and the best way of getting to and from it. It’s usually best to figure this out while you have a bird’s-eye view and the option to go elsewhere. If you need to, loiter over the field until you not only know your approach and landing setup, as well as your plane plan to optimize your ground operations.

Once you’ve landed, it’s your runway. Don’t leave it until you have clearly identified a safe path to parking. You may even want to taxi to one end, shut down and scout on foot. Don’t let your haste to clear the runway put your ground operations at risk.

Losing Directional Control

A common mishap disproportionately striking those off-pavement is loss of directional control either on takeoff, landing or during taxi. For high-speed operations associated with flare or rotation, a not-so-smooth runway surface is akin to driving down a washboarded gravel road. It’s easy to lose control.

In addition to rough surfaces that may facilitate loss of control, there also is the issue of changing surface friction. Both wet grass and dry grass can be exceptionally slick, making braking or differential braking to maintain directional control a crapshoot.

Many unpaved runways are also width impaired. If your plane starts to waver, there may not be a lot of latitude for forgiveness. Obstacles adjacent to unpaved runways may be closer than your realize and can include fences, cars, ditches, cows, etc.

Excessive Technique

One reason to get off pavement is to experience the real reason we learn soft field technique. For nosewheel aircraft, the assumption is that you want the weight off the nose to prevent it from hitting something and collapsing or getting mired into something soft. In the real world, you must find the balance point between keeping the nose up and recognizing that not all unpaved runways requires exaggerated soft field technique.

While off pavement, get a feel for what is required, not what you were taught. Don’t be so fixated on keeping the nose up if you aren’t getting mired down. You may also want to look ahead of you or do the old S-turn maneuver to make sure the path in front of the plane is clear.

Hidden Obstacles

There are rarely hidden obstacles on a paved runway. Obstacles on pavement are considered FOD (foreign object debris—see Aviation Safety’s February 2015 issue). For unpaved airstrips, particularly in the dry western part of the country, the entire runway may be paved with FOD. Some runways, particularly the emergency strips in the desert of Idaho, consist of rocks, cobbles, gravel and occasional clumps of grass that would likely meet the definition of FOD if found on a paved runway.

In addition to the FOD that some runways are made of, there also are gopher holes or, worse yet, badger holes. There also are holes from removed tree stumps or rocks. Before venturing off pavement, do your homework on the condition of the runway surface as reported by other pilots or locals who use the strip. Be mindful that rough is a very relative term. Somebody with 29-inch Alaska bush wheels and tires on a Super Cub may report a surface as smooth and in great condition. The same field might make a Mooney driver give up flying. Tire size matters when it comes to assessing the condition of a rough surface. Don’t be fooled.

The Rewards

So we have covered the risks of off-pavement operations. So why bother? The rewards can be sublime. For people interested in earning a tailwheel endorsement, both wet and dry grass are forgiving surfaces for mastering the art of tailwheel landing techniques. Most instructors recommend mastering landings on a nice friendly grass surface before daring to touch down on pavement, where the direction in which you land will be the direction the plane goes when both tires touch.

While there are many paved airstrips in the U.S., there are many more non-paved opportunities. As more states adopt recreational use statutes eliminating the liability of the land owner, more strips will open up for public use. For people traveling across the continent for business or pleasure, mastering the unpaved runway provides more options for emergency landings, as well as discovering local color you’ll never see at a big-city FBO.

Off-pavement experience also prepares a pilot for the day the engine stops and the only option is an off-airport landing. Knowing what different surfaces feel like and mastering your technique for landing on them teaches you the involuntary deadstick skills that can keep your plane from flipping over on touchdown.

Finally, there is the benefit of the romance and the feeling of superiority over paved pilots. This is not a safety or risk management factor, but in looking back in my logbook, I can say the best experiences, the best airports and some of the best people I have met have been off the paved path. Getting comfortable with your own off-pavement technique will earn you the chance to rub elbows with some of the finest people you’ll ever meet, along with indelible memories.

Mike Hart is an Idaho-based commercial/IFR pilot and proud owner of a 1946 Piper J3 Cub and a Cessna 180. He also is the Idaho liaison to the Recreational Aviation Foundation.