Congratulations. You just spent the last three hours in the clag, smoothly and calmly managing ATC, your GPS navigator and the autopilot while successfully piloting yourself and your passengers from Big City International to Non-Towered Regional for your business meeting. Breaking out on the GPS final, you cancel IFR and switch over to the CTAF to announce your straight-in approach, only to look up to see a Skyhawk-filled windshield.

288

After the few moments of stark terror it takes to dodge the traffic, you slam the mains onto the runway and taxi in, still shaking, wondering what the heck just happened. Where did that guy come from, anyway? Isn’t everybody out here operating IFR in this weather? And why didn’t ATC tell me there was traffic in the pattern? The answers involve the sometimes-confusing transition from the IFR system to a non-towered facility and some common mistakes. Let’s explore.

Welcome To Class G Airspace

That Skyhawk’s driver was perfectly legal (but perhaps not without additional risk). So were you, on both counts. The trick has to do with how Class E and Class G airspace exist, how and when they begin and terminate, and the weather underneath the cloud layer you just penetrated.

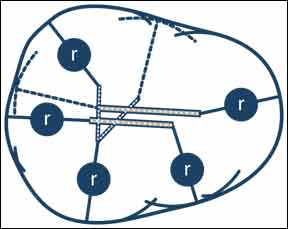

Basically, Class G exists everywhere its not designated something else, like A, B, C, D or E airspace. In this case, Class G exists underneath the Class E airspace and at the non-towered airport’s surface. One thing to remember here is Class E airspace—the kind in which you were flying when maneuvering for and descending on your GPS approach—has its floor at 700 feet agl. The VFR visibility and cloud clearance requirements in Class E and when below 10,000 feet msl, of course, are three statute miles and 500 feet below, 1000 feet above and 2000 feet horizontally.

If the visibility underneath the cloud layer was at least three miles and the ceiling was at least 1500 feet agl, the Skyhawk was perfectly legal to be at or below a 1000-foot pattern altitude, even in Class E. And if the ceiling was lower, there’s little to prevent its pilot from flying the pattern at an altitude guaranteed to keep him or her at least 500 feet below the clouds.

We also need to point out that, beyond the non-towered airport’s immediate vicinity, Class E stops at 1200 feet agl, so the Skyhawk could be arriving or departing and, as long at it remained wholly within Class G airspace, was perfectly legal to be there. Note: We’re not passing judgment on the Skyhawk pilot’s wisdom, just whether he or she might be susceptible to FAA enforcement action. All of this, of course, is charted on the local sectional, an example of which is depicted in the sidebar on the previous page. What? You’re not carrying a VFR chart for your destination?

One other thing to keep in mind: This example involves a non-towered field with a published instrument approach. At a nearby airport, similarly non-towered but lacking a published approach, Class G airspace extends upward to 1200 feet agl. When you descend for that airport, reach the controller’s minimum vectoring altitude and cancel IFR, you’re doing the same thing the Skyhawk driver was doing, with the same visibility and cloud-clearance requirements.

288

The only other variable here is whether the weather is, in fact, at or above the Class G minima. At a non-towered facility lacking an automated weather observing facility, the current conditions are, shall we say, open to interpretation. We’d gently suggest if you can see the far end of a 3000-foot the runway from short final, the flight visibility is at least a mile and, as long as they remain clear of clouds, there definitely can be someone else out there.

Straight-in Or Circle?

In our example of arriving at Non-Towered Regional, we broke out on the GPS final and flew a straight-in approach to the runway. Can we do that? When and why might we want to circle, even if the wind favors the straight-in? If we do choose to circle, is there anything we need to do before arriving at the specified minimum descent altitude (MDA)?

Yes, we can fly a straight-in final when the approach plate includes a published MDA for it. The other giveaway, of course, is the approach’s name: those including a runway designation and lacking a letter are aligned closely enough with the runway to allow us to fly straight-in. The tolerance is the final approach course must be within 30 degrees of the runway’s alignment.

288

Flying a straight-in final, however, might put us in conflict with VFR traffic at the airport (our ubiquitous/problematic Skyhawk, for example). Instead, it sometimes can be advantageous to join the VFR traffic pattern. Examples of when this is a good choice include when it’s busy and flying the straight-in will disrupt traffic flow (remember, too, the airplane lower than you in the pattern has the right of way, and basically, every other type of aircraft enjoys right of way over a powered airplane).

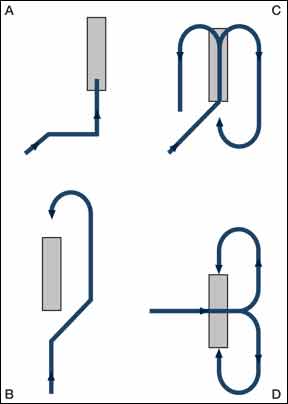

Joining the VFR pattern after breaking out on the approach but before landing does require a bit more planning. For one thing, we should not descend below the published circling minima if we intend to circle or join the VFR pattern. If we do, descend lower than the circling minima, we either need to stay there are climb back up to the higher altitude, which is established for terrain and obstacle clearance. That means we also must accept higher ceiling criteria, as well as fly the airplane to comply with the circling maneuver. For example, when circling, we can’t fly the airplane faster than the speed allowed for the category’s altitude. Other considerations apply, when circling, of course. See the sidebar on the opposite page for some of them.

But joining the VFR pattern at a non-towered facility is a good idea pretty much any time the weather allows it. Put simply, you can’t know who else is out there, putting around. Perhaps they don’t have a radio; perhaps they’re on the wrong frequency. Perhaps you’re on the wrong frequency. Flying a normal VFR pattern absolves you of a lot of sins in this environment. None of which, of course, should preclude you from flying the straight-in when necessary and appropriate: doing so is legal, moral and non-fattening.

On Your Own

Despite the foregoing tips and traps, arriving IFR at a non-towered airport isn’t rocket surgery. Most of the time, you discover why there’s no tower: there’s also no traffic, and you have the place to yourself. But you can’t know that until snugly parked on the ramp.

The hand-holding we get when using a towered airport can make us complacent, although some of the same considerations and concerns outlined here apply there, too. The punchline is we need to be better prepared and a bit more cautious—especially when it comes to potential traffic conflicts—when we’re out on our own. And don’t forget to dial in the destination’s CTAF on the other radio and monitor it while inbound. You never know what information nuggets you’ll hear.