Most pilots have heard warnings about the timeliness (or lack thereof) of Nexrad radar. Better expressed as latency, the weather you see on your tablet, smartphone or multi-function display from providers like SXM or the FAA’s ADS-B could already be 15-20 minutes out of date. It can’t be said enough: What you see on your Nexrad display is better described as a historical record and has little to do with what’s happening right now.

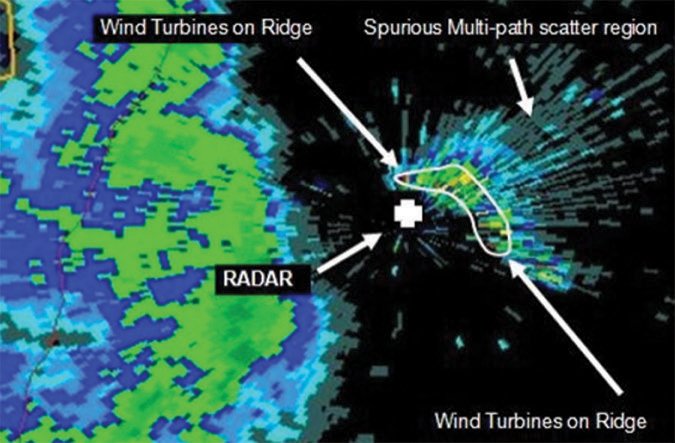

Less often discussed—or warned about—are the radar gaps, the places where there is only a partial picture. At best, the conclusions we draw when viewing weather radar where gaps exist can be misleading. At worst, they’re completely wrong. (And weather radar isn’t our only concern: depending on where we fly, ATC radar often has gaps in its coverage, especially at personal-airplane altitudes.) Essentially these radar gaps—especially the weather-radar kind—are what we might call “known unknowns,” and pilots would do well to be very wary of them. The good news is they are somewhat predictable if you know what to look for.

Different Radars

Weather radar provides the best overall weather picture nearest its station. But as the distance from the station increases, the weather picture will increasingly show only what is happening at high-altitude, and it can totally miss what is happening near ground level. I have seen frog-strangling downpour cells at ground level when the radar shows an area of light precipitation, because that is what the radar sees in the higher part of the cloud.

It’s important to remember ATC radar coverage is slightly different than weather radar, but has similar limitations. There are gaps. In certain parts of the country you will hear the words, “Radar coverage lost.” You’ll be given a 1200 squawk and a pat on the back if you’re VFR, maybe with the next ATC frequency. If you’re IFR, you may also hear something like “you are entering an area of poor radar and radio coverage. If we lose contact, change to the next frequency 132.4 in 40 miles and report over the VOR.”

Understand The Gaps

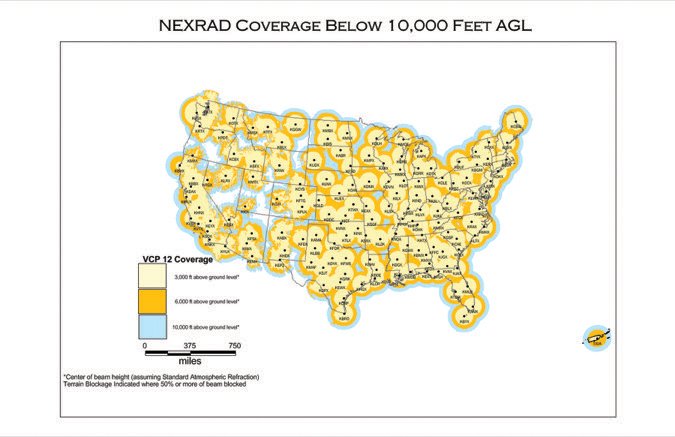

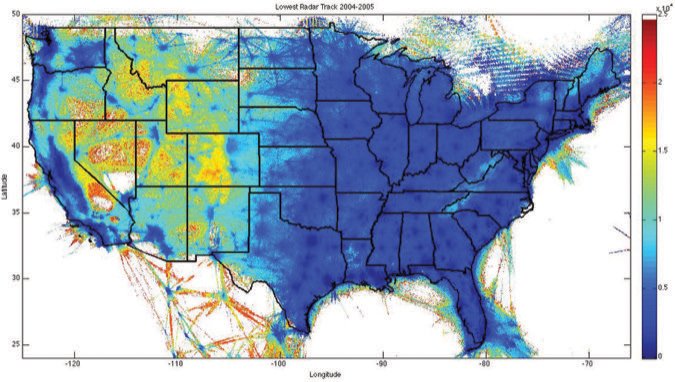

Radar beams (and radio signals) generally travel in a straight, line-of-sight path, so the information available from radar waves is limited by what they can “see.” The top three issues causing radar information gaps are: 1) the distance between radars (typically ~215 miles/345 km in the western U.S.); 2) mountains and other terrain blocking radar beams; and 3) the Earth’s curvature, which limits the ability of long-range radar to observe the lowest parts of the atmosphere, that which is at less than 10,000 feet and distances greater than 108 miles/175 km.

There is a bigger problem that the gaps compound, which is that the planet is round. The farther the weather, or your aircraft, is from a radar dome, the more the Earth has curved away from the beam, so the more limited will be the radar coverage. The best and only weather picture will be of the mid- and upper atmosphere. The problem for pilots is that most of the precipitation or hazardous weather we encounter and are concerned with occurs in the lowest three kilometers (~10,000 feet). If you are in a coverage gap and a significant distance from a radar dome, that is precisely the atmosphere unreported by radar.

But Nobody Told Me

Just as for ignorance of the law, ignorance of aviation weather is no excuse. The law is that pilots shall obtain all available information regarding current and forecast weather prior to departing for a flight, and looking at radar is part of that information. In reality, any two pilots looking at the same Nexrad radar display might see a slightly different picture of what the weather actually is. One of them will think the radar returns show where the precipitation is and is not.

The other may be more aware of the limitations of the radar weather products, or has reason to be skeptical, perhaps from tribal knowledge or from reading this article. Whatever the reasoning, especially in gap areas, it is a good idea to take any radar picture with a substantial amount of salt.

On the fine spring day that I write this, the weather forecast for my day’s flight—Boise, Idaho, to Burns, Ore.—includes the possibility of afternoon showers and thundershowers that could cause brief marginal VFR conditions in the forecast area. The TAF for my destination implies the same, stating scattered showers in the vicinity of the airport. Looking at the radar, I can see manageable patches of precipitation between my location in Boise and my destination, with most of the patches nearer to Boise and appearing to dissipate to the west. One reasonable interpretation would be that the bulk of the system has already moved, from west to east, leaving my destination in the clear.

In actuality, I found the same patchy distribution of scattered showers from Boise to Burns, even though the zones of rain I could see out the window were not on my iPad Nexrad weather plot. And when I arrived, I had to dodge and weave through the same types of scattered precipitation that was around Boise. Sure, the radar looked clear, but that was due to the low height of the rain clouds and the gap in the radar coverage, not a gap in the weather.

Tribal Knowledge

Fortunately for me, it wasn’t a big surprise. I knew that Burns, like my hometown airport of Salmon, Idaho, is in a weather radar blind spot. But I didn’t find this knowledge on my own, nor from some aviation product, nor from a weather briefer. Instead, it came to me by word-of-mouth from another pilot who trained me on the route and others who know and fly in the area. This tribal knowledge has been confirmed and reconfirmed by what I have seen out the window, but for some reason, tribal knowledge does not make it into many weather lessons.

Pilots should be aware that the places where the radar’s vision starts to become blurry, the known unknowns, are not clearly depicted. They may show weather pictures that are typically better than what you find in reality. Terrain adds a double whammy because the same terrain that causes radar blockage is often a cause of the weather itself. When there is terrain, the area of low radar confidence has elevated importance. Not only might you find unforeseen weather, you might also find some granite.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology/Fabrice Kunzi.

Who Cares?

The U.S. weather radar network now known as Nexrad is mostly built around the need to predict the kind of severe weather pilots don’t want to fly in (i.e., thunderstorms, tornadoes, hail, etc.). Most of the U.S. has weather radar coverage, but not all. For example, there is a significant weather radar gap over central North Carolina. Areas around Charlotte and Greensboro are sometimes in peril from surprise tornadoes that have spawned off the radar. There are also significant dead zones in Virginia, Pennsylvania, Louisiana, and a big chunk of eastern Texas. The mountainous west, of course, has more gaps than a buck-toothed mule.

The motivation for a 2009 report on the feasibility of new technologies to fill coverage gaps in national weather radar network were tornado and coastal storm-induced injuries, fatalities and economic losses in the states of Wyoming in 2005, and Washington in 2007. In 2012, a significant tornado in North Carolina didn’t show up because the rotation was below the radar limitation of 8500 feet AGL. A major coastal storm near Oregon in 2017 swept inland (under the radar), giving the appearance of a gap in the system that in reality was just a gap in the radar.

The concern here is for pilots and the significant gaps below 10,000 feet, where most weather and personal aircraft concentrate. Yes, most of the U.S. has radar coverage by both ATC and weather radar, though not all of it. And yes, if you climb to the flight levels, generally you will be found by ATC and the precipitation above 18,000 will likely show up. But in the radar gaps, especially below 10,0000 feet, it is all too easy for a pilot looking to find a gap between weather systems to head into an opening that actually isn’t there.

ATC Radar, Too

Although it is a slightly different issue, ATC radar (and radio) coverage also has similar spottiness and coverage limitations due to interference of terrain with line-of-sight broadcast. Just as the terrain and opportunity to encounter interesting weather rises, radar and radio coverage begins falling.

There are a lot of benefits to staying in radio contact, like flight-following for VFR pilots and remaining in contact with center for IFR pilots. On a typical jaunt through the mountains, I will be below radar coverage but still in radio range.

When you run out of the range of one antenna and into the range of the next one, you get a frequency handoff from one frequency to the next because they are about to lose you. Pay attention because if you get it wrong, there is a very limited time to return to the old frequency to pick up the change again.

To receive and be heard, your aircraft must broadcast more or less in the line-of-sight of an ATC antenna. VHF radio waves have the same line-of-sight limitations as radar waves (they are basically the same electromagnetic phenomena, but at different frequency ranges that are subject to slightly different bending and reflection. The locations of radio gaps are not necessarily the same as the gaps in ATC radar coverage. Radio antennas are also cheaper to install than radar systems so it isn’t nearly as expensive to maintain radio coverage across the entire conterminous U.S.

Caveat Emptor

If at all possible, forearm yourself with knowledge of where the gaps are. Acknowledge that there are unknown unknowns, areas of ignorance. Don’t assume you have a complete picture when you are flying into gappy radar coverage. Because of the region I fly, I know the areas where there are gaps in radar or where I could be misled by a radar picture. I am not likely to be flying when storms are particularly strong, but I know better than to assume that two zones of red precip separated by a nice area of light green is a real gap.

Mike Hart flies his Piper J3 Cub and Cessna 180 when he’s not schlepping people and their gear. He’s also the Idaho State Liaison for the Recreational Aviation Foundation.